A series where Michael Xin sifts through freeware games to find you those hidden nuggets of gaming gold.

My journey to stave off boredom has brought me to the untamed wilds of the digital Klondike, where the air is untainted by price-tags and the data-rivers flow with gold aplenty if only one knows where to look. For every hundred shovelware titles on the net, there’s bound to be a nugget of something worthwhile beneath the rapids of Google’s search pages waiting to be uncovered.

Much like what fueled the frontiersmen spirit of those Klondike Gold Rushers, this week’s game is about greed, industry, and Icarian ambition. Just replace the greedy humans with greedy Tolkienesque Dwarves (and humans and Elves and others too), and you’ve pretty much got the gist of it.

Dwarf Fortress first caught my eye back in 2012 because of Minecraft. Then a humble penniless indie game company, Minecraft’s then pimpled homepage displayed its inspirations unabashed, listing Dwarf Fortress (alongside “Infiniminer and others”) prominently next to its own game’s download link. Everyone knows Minecraft, but I’d wager few realize that Minecraft’s own dreams of procedurally generated worlds, wilderness survival, and construction work were pages straight from Dwarf Fortress’s playbook. Being then hooked on pixelated creativity I ventured forth carelessly – What I stumbled upon was one of the most ambitious projects in gaming, yet unfortunately it was also an experience I was wholly unprepared for.

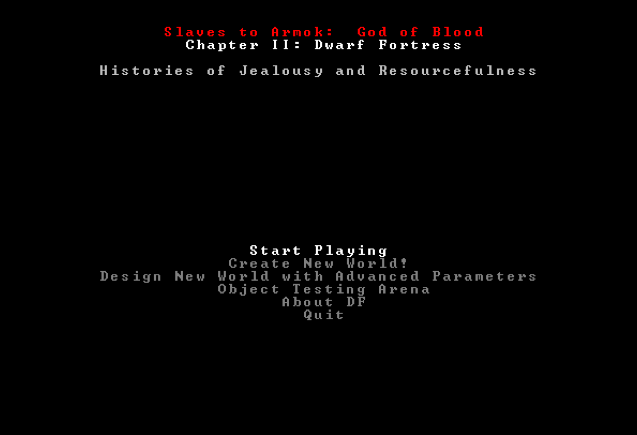

The terminal window the game hijacked opened the gates to an ASCII hell. Dancing multi-coloured characters wrenched me from the graphical comfort zone of modern gaming, and suddenly I had to fill in the blanks with my imagination. It was surreal, like trying to decipher a novel written in another language as the author writes it in real time. The base game having no mouse control, no tutorial, and most of all no graphics wasn’t doing it any favors either. For the first time I found a game I couldn’t comprehends because it was hidden behind an impenetrable, literal wall of text.

This part of the game hasn’t changed, but fortunately there are third-party tools to remedy it. The devoted modding community offers many workarounds, with the flatteringly named “Lazynewbpack” as an end-all to UI-related problems. Once you ease into the clunky UI, Dwarf Fortress offers an organic, procedurally generated experience like no other, granting players freedom to experiment with the game’s realistic physics engine, complex AI personalities, and hilariously terrifying procedurally generated creatures.

Before actually delving into the two and a half modes the game has to offer, you must first generate an entire fantasy world, complete with lore, civilizations, wild life, geography, and a sprinkling of magic. The eponymous “Fortress Mode” has you overseeing a group of Dwarven colonists in establishing a new colony somewhere in the wild, and that is literally all the context you are given for the game. Part architectural planning and part unit micromanagement, what you do with these inebriated mountain-dwellers is entirely up to you, and the game provides the tools for you to accomplish any mad project you can imagine. Of course, for new players what you will mostly be learning is how to keep your Dwarves alive in a hostile fantasy universe, facing the challenges of not just mundane food shortages, but also goblin invaders, were-creatures, and worst of all, Elven traders. However, it can be frustratingly difficult to understand the many opaque layers of mechanics and interactions beneath the migraine-inducing ASCII graphics.

I remember having to download a published manual of the game from a shady site to learn the game (its official wiki was several patches behind). The manual was at least 100 pages long and this was in the year 2012. Furthermore even after diligent study the game’s “Adventure Mode”, which promises open-world exploration of your fantasy world, still remains utterly incomprehensible. For those of you wondering, the wiki has since been updated, but the game still remains obstinately unapproachable for newbies. One reason for this steep learning curve is the sheer breadth of detail the game seeks to tackle, the other is likely because the developers treat Dwarf Fortress as a labor of love, with no marketing expectations, and are paid for their work by donations from their fans.

One cannot ‘win’ Dwarf Fortress. There is no goal the developers intend for you to accomplish. All Dwarven endeavors ultimately teeter towards ruin in some stark unintended metaphor for human history. “Losing is Fun!” is the unofficial motto of the game for a good reason, since every fortress you found is like a sandcastle waiting to be leveled at the end of the family vacation. A fond memory of mine was when several were-asses (imagine a werewolf, but half donkey instead of wolf) contained underground in the former residential tunnels broke free during an accidental flooding. These were-asses were once hardworking members of my fortress infected and quarantined during a previous incident, and would transform every full moon to spread the incurable plague violently. The pack of donkey monstrosities rampaged through my fortress until being finally put down by my militia, but not before goring and infecting a good portion of my Dwarves. The entire settlement was soon abandoned because I couldn’t handle the routine were-ass outbreaks.

There are countless differing accounts of these “Losing is Fun!” moments in Dwarf Fortress because the game has so many different simulated objects serendipitously interacting with each other. Online stories like “Roomcarnage” and “Boatmurdered” are equal parts fascinating, gruesome, and unpredictable because you can never expect what the game will come up with next. What Dwarf Fortress truly excels at is creating a framework for you, the player, to construct your own epic fantasy account with twists and turns, profit and loss, ambition and failure, all culminating in a climactic conclusion.

Was it worth my time to learn the game? Certainly. But Dwarf Fortress isn’t for everyone, and sometimes its own ambition gets in the way of its enjoyability as a video game.

Dwarf Fortress is an old game, and is still far from perfect. Every month the two brothers that started it all sit down and mail out commissioned crayon drawings to their patrons as a symbol of appreciation, using the donations of fans to work on the game like monks in the middle ages. The game has been in active development for eleven years, with the current version number roughly indicating its completion percentage. Tarn Adams, the developer, estimates it will take another twenty years to complete the game. The world’s foremost drunken little people simulator still has no boats, lackluster magic, and a severely malnourished economics system among other problems. Most unfortunate of all is the game’s poor optimization; Your fortress is far more likely to perish from a veritable “FPS Death” (frames per second) than any forgotten beast or goblin invasion.

Yet regardless of its flaws, the game has been featured in the New York Museum of Modern Art in 2013, selected as PCGamer’s “Best Free Game” in 2016, among other honours, for a good reason: There’s nothing out there quite like it, and there’s a good chance there never will be.