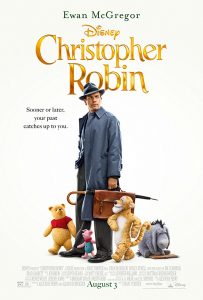

Poster of ‘Christopher Robin’ (source: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4575576/mediaindex?ref_=tt_mv_sm)

The stories of Christopher Robin, Winnie-the-Pooh and all the other inhabitants of the Hundred Acre Wood are so well-beloved and such sacred ground that no film or adaptation can ever truly do justice to them, and will certainly never please everyone. Christopher Robin, from director Marc Forster, is far from a perfect film – at times too slow, at others too sad, and often simply too odd – but it nevertheless manages to appeal to nostalgia, to find delight in the characters, and to entertain and charm its audience.

The central premise itself is a strange and somewhat confusing one: although Christopher Robin was indeed a real person, based upon A. A. Milne’s own son, the film revolves around a fictional Christopher Robin who really went to the Hundred Acre Wood (through a tree in his garden) and really talked to and interacted with the ragtag mix of sentient soft toys and talking wild animals that lived there. After leaving them behind as he grew up, the now adult Christopher Robin (played by Ewan McGregor) re-encounters them all, and thus rediscovers the importance of play, imagination, and going on holidays.

Winnie the Pooh (Jim Cummings) and Christopher Robin (Ewan McGregor) in ‘Christopher Robin’ (source: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4575576/mediaindex?ref_=tt_mv_sm)

The facts that the tree is a literal portal to some vast and otherwise uninhabited forest (that still remarkably resembles Sussex), and that the toys are not alive only in Christopher Robin’s mind but are actual, real, walking-talking creatures visible to all, are never explained or questioned. Forster, who has also directed Quantum of Solace (2008), and World War Z (2013), is clearly trying to push the square peg of fantasy children’s literature into the round hole of cinematic realism, and instead ends up with a strange and at times somewhat unsettling supernatural edge to the film.

Christopher Robin particularly struggles in its long, drawn-out opening. Despite this iteration of Christopher Robin being almost entirely fictional, the opening segments are presented as a slow, sombre biopic, a pretty generic tale of a difficult childhood, involvement in the War, and subsequently settling down to a comfortable middle-class existence. With intermittent imitations of Milne’s chapter headings and E. H. Shephard’s famous drawings, this section feels like a very stretched title sequence, and the continuous mood of melancholy make for a decidedly dull introduction. The cinematography, by Matthias Koenigswieser, and music, by Jon Brion and Geoff Zanelli, are perfectly pleasant to the ear and eye; performances from McGregor, Hayley Atwell as his wife Eveyln and Bronte Carmichael as their daughter Madeline are all nicely nuanced. Apart from the slightly out-of-place (though nonetheless skilled) comic moments from Mark Gatiss as McGregor’s hapless boss Giles Winslow, however, overall nothing really stands out.

The Family in ‘Christopher Robin’ (source: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4575576/mediaindex?ref_=tt_mv_sm)

After the arrival of Pooh, however, the film really gets going. After his semi-arcane summoning by McGregor’s spilling of honey over a childhood drawing, the trademark Winnie-the-Pooh humour – playful, absurd, childish, endlessly entertaining – starts to shine through, and the unlikely double-act makes for some excellent comic moments. Jim Cummings has been voicing Pooh and Tigger for over 30 years, and his voice work here is spotlessly brilliant. The characters themselves are actually animated, in the same vein as Spike Jonze’s Where The Wild Things Are, as real, furry, tired and dirty toys and animals, and details like faded colours, matted fur and unblinking glass eyes, while often verging on the uncanny, succeed in creating lovable little creatures. The animation department have done a fabulous job of producing so much facial nuance in their creations, especially in Pooh, allowing the voice work to shine in the characters. Brad Garrett in particular performed brilliantly as the laughably, lovably morose Eeyore, alongside Nick Mohammed as Piglet, Peter Capaldi as Rabbit and Toby Jones as Owl.

The fabulous job of the animation department in ‘Christopher Robin’ (source: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4575576/mediaindex?ref_=tt_mv_sm)

It is undeniable that the film resolves into schmaltzy, tired platitudes about the importance of fun, imagination, and friends and family. After a climax that is exciting despite its imminent predictability, featuring comic cameos from the likes of Simon Farnaby and Mackenzie Crook, all is happily resolved and the villain of adult responsibility vanquished. The film here seems to return to the children’s entertainment side of things, something far closer to a film like Paddington than the moody opening exposition. It is, clearly, a film of two halves, and while this disconnect does not work at all to its advantage the film still manages to overcome its teething problems and create a charming conclusion. While likely a little too saccharine for some, a viewer would be hard-pressed not to be won over by the sheer playfulness of the latter part – its brilliant characterisation of Pooh and all his friends, the dialogue sparkling with wit and joy, is surely appealing to all tastes and ages, just like Milne’s classic works themselves.

Christopher Robin (2018): Directed by Marc Forster. Written by Alex Ross Perry, Tom McCarthy, Allison Schroeder, Greg Brooker and Mark Steven Johnson based on characters created by A. A. Milne and Ernest Shepherd. Starring: Ewan McGregor, Hayley Atwell, Bronte Carmichael, Mark Gatiss, Jim Cummings, Brad Garett, Nick Mohamed, Peter Capaldi, Sophie Okonedo, Sara Sheen, and Toby Jones.

This review was written about a film shown by The Bede Film Society. Next week they are showing ‘Crazy Rich Asians.’