The 11th November 1918 saw the end of the ‘Great War’. An estimated 15-19 million people had been killed, a further 23 million military personnel had been wounded, and 8 million civilians had also lost their lives. How far was World War I a turning point for the way the world works today?

The 11th November 1918 saw the end of the ‘Great War’. An estimated 15-19 million people had been killed, a further 23 million military personnel had been wounded, and 8 million civilians had also lost their lives. How far was World War I a turning point for the way the world works today?

The First World War led to a vacuum of power in many European states, allowing a new wave of political ideologies and systems. The most obvious and catastrophic of these was the ultimate rise of Adolf Hitler’s Nazism in the 1920s and 30s. This uprising proved to have devastating global consequences throughout the 20th Century, starting, of course with World War II. German Nazism found its roots in the passage of the Treaty of Versailles in 1920, leaving Germany essentially bankrupt; hyperinflation and European armies of occupation led to growing anger and a feeling that there must be someone to blame.

This is where Adolf Hitler found fame, by blaming any and all minorities that he could get his hands on, whether it be the disabled, Communists or, most famously, Jewish people. This ideology of hatred and prejudice spread throughout Europe at an alarming rate, with Mussolini leading a fascist dictatorship in Italy, and Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists gaining an estimated 35,000 supporters. World War II (1939-45) saw Britain and the allies fight to eradicate fascism from European, and global, politics. Nazism appeared to have been sufficiently quashed, in mainland Europe at least.

Recent events have, however, reversed the feeling that fascism had been banished to the history books. In 2016, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) won 13% of the popular vote in the German election on the back of a campaign that sought to end immigration, eradicate Islamic influence in Germany, and return to the nationalistic days of the 1930s by leaving the EU. Donald Trump’s rhetoric, whether he believes what he says or not, is equally reminiscent of the populist beliefs that fascists across the world were famed for, calling Mexicans “rapists”, for example, sounding eerily like the common description of the Jewish race as “rats” in Nazi Germany. Most worryingly of all however, is that this vitriol is having an effect in countries that have little history of fascism and extreme nationalism.

Just a matter of weeks ago, Jair Bolsonaro was elected President of Brazil. This is a man who is anti-abortion, homosexuality (he told Playboy magazine that he “would be incapable of loving a gay son”), secularism, and affirmative action. He also, in a very Hitler-esque moment, called the era of military dictatorship in Brazil “glorious”, and would that it returned to that type of political system. This all points to the fact that the end of World War I created a dangerous atmosphere for political extremism, in which far-right feeling could grow, fracturing the world in a more obvious fashion than ever before.

On a more practical level, World War I saw the use of modern technology as a way of causing mass injury and destruction. At the time, this included the use of chlorine gas to suffocate the enemy, the use of aircraft to drop bombs on enemy towns and troops (to varying levels of success), and new semi-automatic weapons. There were two major issues with this. One, the use of new weaponry meant that engineers and scientists on both sides of the conflict then spent years trying to create bigger and more brutal weapons than ever before. Two, it resulted in a huge number of civilian casualties, many of whom were simply collateral damage.

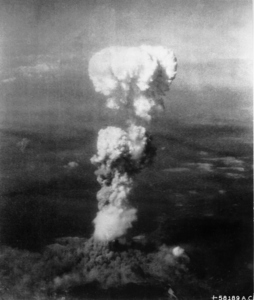

Both of these problems continued long after World War I, most notoriously combining in the form of the advent of the nuclear and atomic bombs, dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the USA in 1945, thus essentially ending World War II. This was a hugely contentious act from the USA. On the one hand, it did end the war, which had become something of a stalemate, and so it may well have saved the lives of millions more soldiers in the battlefields of central Europe. However, the effects of the atomic bombs dropped on Japan are still being felt today, they caused much more damage than was first thought. Water sources remain contaminated, nuclear radiation resulted in the local ecosystem being destroyed, and cancer rates have increased among victims by an estimated 10-44%, depending on how close they were to the blast site. So true, only 200,000 people were killed in the blast and immediate aftermath, but the lives of millions more have been impacted, purely because they happened to be unlucky enough to live in these towns.

I wish I could say that this disregard for civilians ceased after the end of World War II. But that just isn’t the case. In recent conflicts in the Middle East, for example Syria, Libya, Iraq and Afghanistan, the use of air strikes, AI, and false information has led to approximately 4 million deaths since 1990. I’m thankful to say that the number of civilian casualties is significantly lower than that of World War I, but that still doesn’t mean to say that we have learnt from our ways regarding the treatment of innocent bystanders in war zones across the globe.

We’ve all seen images of Vietnamese children running away from helicopters pouring Agent Orange all over forests and towns, or of Somalian or Yemeni families in plastic tents, malnourished, homeless and distraught, and all because they got caught in the crossfire of a war they more than likely objected to. This is, it must be said, another grim legacy of the First World War.

Allied intervention in the Middle East has had, and continues to have, a devastating impact on the region and civilians stranded there

There is significant debate around whether World War I was really necessary in the first place, particularly from a British perspective. Oxford historian Niall Ferguson describes Britain’s intervention as “the greatest error in modern history”. There is certainly sufficient evidence to agree with this, after all we did only really get involved in the war because troops marched through Belgium, with whom we were allied, not because there was a direct threat to our democracy or way of life. The real beginning of World War I was the assassination of Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Serbian Gavrilo Princip, clearly showing no direct consequences for Britain.

Again, we can see reflections here between our involvement in the Great War and our interference in later conflicts, the most infamous example being that of the invasion of Iraq by Britain and other forces based on limited evidence and necessity. Having said this, I believe that there is an argument to say that, had Britain not entered World War I, it is possible that the world would be a very different place, as we did play a key role in the ultimate bringing of (somewhat short-lived) peace to the continent, particularly when it came to naval and air attacks.

So, it’s fair to say that World War I was a significant break from all previous wars and conflicts, paving the way for how the rest of the 20th and early 21st centuries would pan out. But, despite all the negatives that it brought about, whether it be the rise of fascism or the increasingly devastating impact of modern technology, it is important to remember the amazing work of armed forces and soldiers across the world.

Many of the soldiers who fought showed incredible courage to go to war, especially when we think about how young many of these men were. Therefore, as Remembrance Day dawns on us, let us focus not on negativity, but on the invaluable work that soldiers in World War I and onwards do on a daily basis, trying to make sure that the world remains a safe place for generations to come.

We will remember them.