Are we attracted to a new type of hero?

Possibly 10 years ago it might have been the ‘underwear on the outside’, caped, mysterious figure who flies from disaster to disaster saving the damsels in distress and defeating the ‘baddies’. Or the suave, tuxedo wearing, ‘James Bond-esque’ type who drives from disaster to disaster ‘saving’ the damsel in distress and defeating the ‘baddies’.

However, as the years have continued it seems our idea of a hero has dramatically altered. Or has it?

These days, TV ratings appear to show how the intellectual, border-line neurotic characters are becoming the nation’s idols. I bring your attention to a perfect example in the form of highly popular BBC series Sherlock. Granted, Sherlock Holmes is a 19th century creation and could possibly not be viewed as a modern hero, but it is Steven Moffat’s reworking of Sherlock that fuels the fire of his worship.

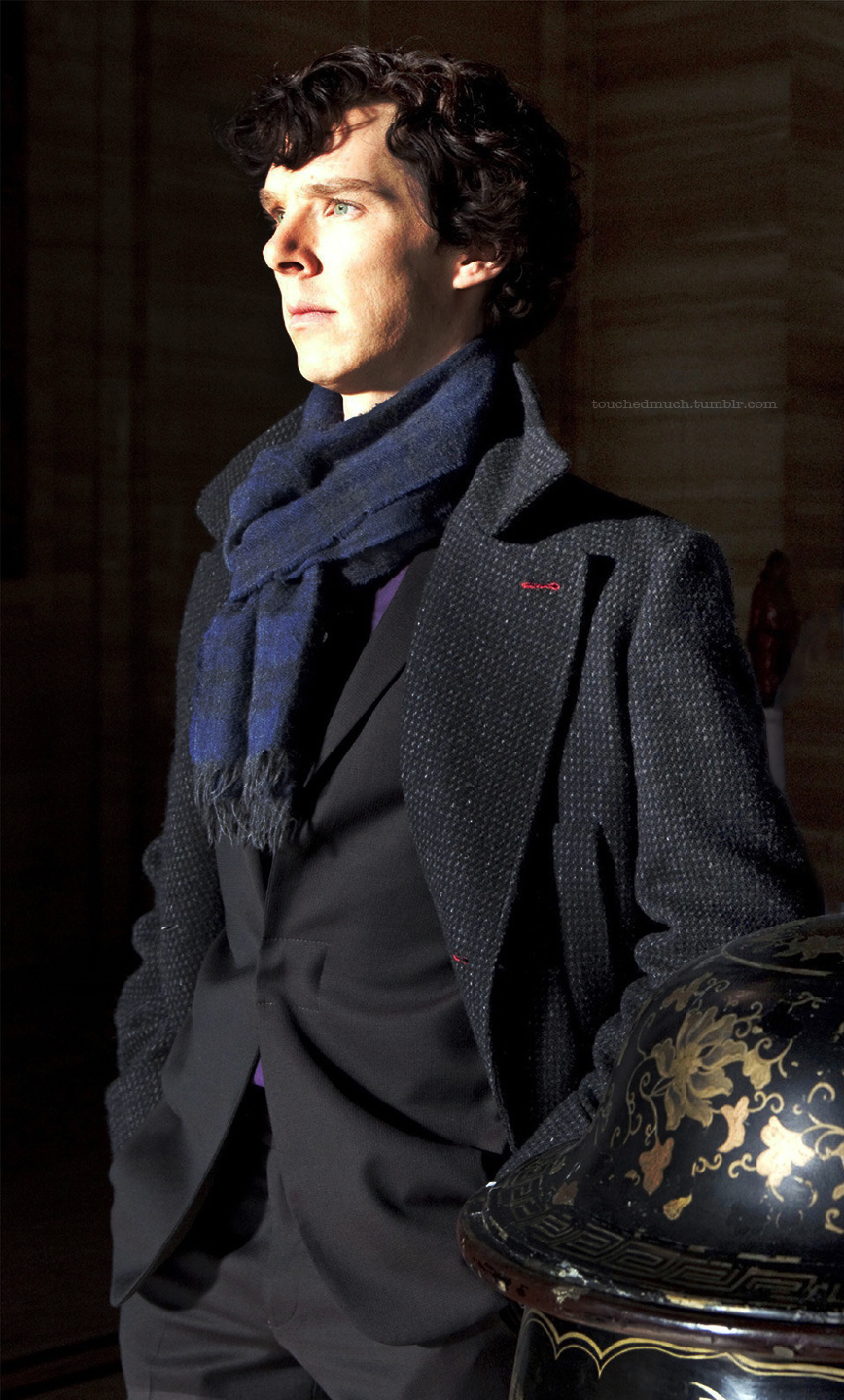

Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock is a work of pure genius and undoubtedly a reflection of the people we admire in our modern world. And yet, to write his characteristics down on paper you could assume the public would take an instant dislike to him; a cold, arrogant egotist with a penchant for saying exactly the wrong thing. Not exactly the personality traits you would want your children to aspire to. So what has made his popularity go global?

Maybe it’s because audiences are tired of the clichéd hero archetype. As mass media begins to expand on a daily basis, it’s becoming increasingly harder for films and TV series to catch and (more importantly) keep a viewer’s attention.

Take students for example, I personally follow the 2 episode rule. If a new series catches my eye, it gets 2 episodes to cement itself as one of the ‘good ones’ otherwise it joins the recycle bin in my brain that’s full of unwatched TV shows, bad album tracks and a significant proportion of my first year notes. So when I see a trailer for a TV show or film it has to prove to me that it’s different. The limited watch-time I have should not be sacrificed to another predictable Jason Statham film (even if they are ridiculously good fun to forecast and complain about!), meaning I need something with a unique plot and original characters to waste my time on.

However, after some thought, we (the audience) can’t be weary of the formulaic heroes. For every counter-example I could give you to the norm, there’s plenty more that fit snugly into Propp’s Character theory (definitely making use of my Media AS Level knowledge!) As two perfect examples of this truism, Doctor Who and James Bond.

Both began in the early 1960s, and have managed to continuously reinvent themselves with various reincarnations of their respective heroes. Doctor Who, although perceived by a few to be a children’s TV show, matches the conventions almost impeccably: a clever, daring, superhuman (literally), male (obviously) protagonist, with his sassy, sexy, wisecracking, warm-hearted, female companion.

Although, this is an improvement on James Bond: the damaged, suave, male Bond who shares his time between shooting incessantly and seducing women who literally have no idea how to survive without a man.

Despite the predictable characters, these and many more like them remain our favourite TV shows/films. So if expanding our fictional heroes isn’t due to our jaded interest in our old stereotypes, why have we embraced these changes?

Perhaps it’s a result of how society is evolving and the increasing need to escape from real life. It’s clear to anyone who’s even seen the trailers for the BBC’s Sherlock that he describes himself as a “high functioning sociopath” and lives up to that label. The audience can never keep up with his logical (if you can call them that) thought processes and they’ve even got a fictional version of themselves on the screen reflecting their baffled looks, in the form of John Watson. All of this lends itself to the possibility that Sherlock offers the ultimate escapism. A protagonist that the vast majority couldn’t come close to understanding, and exploits which seemingly happen under the rest of the world’s noses combine to create the perfect cure for the everyday.

Although, after dissecting Sherlock’s hero identity, I discovered he’s not dissimilar to the heroes of old. A caped (he wears a flowing, black coat), mysterious figure (from one episode to the next it’s difficult to pinpoint an exact character) who flies from disaster to disaster (murder to murder), saving the damsels in distress (mainly John or Mycroft), and defeating the ‘baddies’ (usually some new foes being operated by Moriarty). So maybe he isn’t that different, even if his underpants remain firmly underneath his trousers.

So it seems the further our heroes become from our real identities, the more we welcome them. Because who wants to watch an average human struggling with the depths of life? We could just turn the TV off and stare at our images in the black mirror.