Do we have the right not to be offended?

On a recent edition of the BBC’s Sunday morning show, The Big Questions, the topic for debate concerned the question: ‘should human rights always outweigh religious rights?’ The answer is, of course, ‘what religious rights?’ I was completely unaware that ideas and ideologies had the capacity to hold such things. What the question really meant to ask was: can the rights of religious people trump the rights of those of us without such certainty of the unknowable?

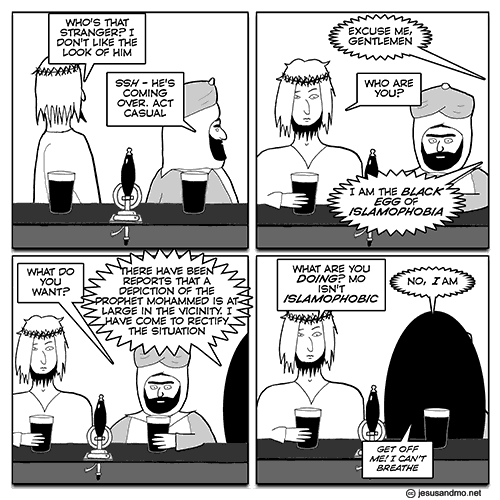

During the show, two students – when encouraged by the presenter – revealed the t-shirts they were wearing. Their shirts displayed a cartoon from a comic strip called Jesus and Mo – an example of which heads this article. The craven BBC refused to show a close-up of the t-shirts (the very subject of debate) leaving the viewer watching from home at a distinct disadvantage.

In the studio audience sat Maajid Nawaz, a (Muslim) Liberal Democrat parliamentary candidate. In response to the general consensus of self-pity from other Muslims in the audience, he asserted that the t-shirts were in no way offensive or threatening to any aspect of his religion. After the show, Nawaz tweeted a picture of the Jesus and Mo cartoon saying that: “This Jesus & Mo cartoon is not offensive and I’m sure God is greater than to feel threatened by it.”

It was not long before the inevitable occurred. Thousands started signing a petition addressed to Nick Clegg urging him to deselect Mr. Nawaz as a party candidate. Many took the opportunity and insisted upon the additional punishment of execution. One particularly vile and ironic message read: “I would insist that this man be beheaded publicly so we can bring peace to our Prophet’s name please Mr Clegg.” It would be prudent, I suggest, that we take such threats seriously; I need not remind readers of the fate suffered by Drummer Lee Rigby.

Last week, both the BBC’s Newsnight and Channel 4 News made a mockery of the journalistic profession by refusing to show the ‘Mo’ part of the cartoon. In a media dominated by pictures, they proved themselves to be utterly spineless when a picture was the news. Channel 4 News stated that: “We’ve taken the decision to cover up the depiction of Muhammad so we don’t cause offence to some viewers.” This is casuistry. They did not show the image, not to spare the hurt feelings of Muslims, but because they are fearful of violent reprisals and the safety of their staff. So the question must be asked of British Muslims, is this the type of relationship you wish to have with the press in this country?

Paddy Ashdown, a man of whom I once thought highly, gave a bumbling and timid performance when interviewed on Newsnight. He began by charging Nawaz with expressing “a minority view”. He pressed us to “understand that in Britain the vast majority of Muslims believe that any image of the Prophet is blasphemous.” When challenged on this point, he decided that statistics were not so important after all and tried, “you don’t have to know what they think, you have to know what their theology is”. Not an unworthy proposition. If only Mr. Ashdown (I refuse to say ‘Lord’) did know their theology. The Koran says nothing regarding the depiction of the Prophet, and only fleetingly mentions an admonition against idolatry – better understood as a prohibition of worshipping false prophets; an indictment, I fear, that all theists would meet.

But here the reader should not misinterpret my argument. If the Koran did explicitly prohibit the depiction of the Prophet, the injunction would shackle only those who chose to chain themselves to the religion of submission. To cry blasphemy is to assume that there is something to be blasphemed. I simply do not share this premise. I do not believe that an illiterate businessman, in a desert, around the year 600 C.E., had the archangel Gabriel re-dictate plagiarisms of the Old and New Testament to him. This story is frankly absurd.

There is a sly and rather nasty manoeuvre pulled by those on the opposite side of this debate that needs unveiling. On the one hand, we hear that we need to protect ‘vulnerable’ minorities who cannot protect themselves. On the other, we are told, in a tone of implied threat, that we have offended the very identity of 1.2 billion Muslims. You must have heard such language before. This is a sinister trick exercised to make one feel at once bullying and fearful. It cannot, and has not, been stressed enough that the individual is the only entity that can hold rights. Groups, unlike individuals, cannot feel pain or offence, and hence have no basis for protection. One’s rights are not amplified when they stand behind the security of a large or menacing group.

A similarly pernicious distortion is employed in the following scenario. You may have heard the defence – when one criticises Islam – that you cannot judge a religion by its most fanatical and reactionary elements. The vast majority of Muslims are tolerant, moderate, and generally amiable people. I quite agree. Why is it then, that when a few hundred murderous Muslims call for the execution of a cartoonist, or a few thousand welcome the complete butchery of free expression, do we treat them as if they were representative of Islam as a whole? If we have to use this stupid word ‘Islamophobic’, this type of representation, I submit, is the perfect candidate.

Islam, you may have noticed, makes extraordinary claims for itself. It says that it is the final revelation, God’s final word – not just for Muslims, but for all of us. We know, in other words, everything we already need to know; no more scientific or moral inquiry is necessary. Well, that’s fine, but if it wants to make such large claims for itself, it must drop the demand that it be protected from the mildest of criticisms and ridicule. Why are we so ready to accept that Muslims have a special or privileged right to be offended?

It is an entirely unmanageable, untenable, and unacceptable situation for one group to hold the rest of society hostage in this way. Two duties, I feel, are owed. The first is for the silent, moderate masses of Islam to stand up behind people like Maajid Nawaz and not allow their religion to be hijacked by their most intolerant members. The second duty – one far easier to fulfil – is owed by the British free press. It is time the media stopped treating the British public as children who are incapable of deciding for themselves whether or not a cartoon is offensive – or indeed, children who could not handle such an exposure. In other words, it’s time that we thicken our skin and broaden the old back, because the ability to express and receive ideas and opinions is far more precious than the right not to have one’s prejudices upset.