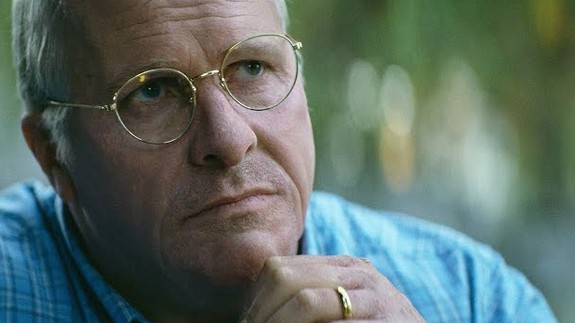

Adam McKay’s depiction of Dick Cheney in new film Vice gives Darth Vader a run for his money. He fetishises the possession of unlimited executive power, launches a violent war to fatten his own pocket, and callously throws aside Donald Rumsfeld who made him the Washington titan he was. I do not refute that we should fear such a scenario. The problem with such a conception is that it overlooks core weaknesses of political cultures that frame the rise of such figures, which should be contextualised in the long-term development of Anglo-American history.

The great historian Fernand Braudel made a career arguing that civilisations scarcely change over vast periods of time. “They change little, and change slowly, after a long incubation which itself is largely unconscious too.” It has certainly been a characteristic of western history that we have been unconscious to all changes. John Pym would surely attest to the truth of this statement. He had not imagined, when he stood before the commons in 1640 in opposition to Charles I’s religious policies, that his words may end in the beheading of a monarch. The moment of the beheading was greeted not with cheers but with a terrible groan from the shocked crowd. Pym, in his use of idealised rhetoric and appeals to the support of the public, had played a dangerous game, and his blunder should prompt us to reflect on our ideal-orientated political culture.

McKay’s Vice itself attests the enduring characteristics of Anglo-American culture, a peculiar outgrowth of the middle-ages. When the Duke of Gloucester commissioned the production of a political treatise on the Fall of Princes, he requested specific examples of practical morals. His request was exemplary of a political culture centred on the cultivation of inner virtue, a framework influenced by the theologian Thomas Aquinas who argued a prince’s role was to work towards the salvation of their community through exercising virtue. Aquinas is renowned for syncretising Aristotelianism with Christian political culture, and even in Jacob Reese-Mogg’s response to Donald Tusk’s bizarre polemic he remains a symbol of political and intellectual virtue. The key thought Aquians melded onto western political culture was the idea of a commitment to res publica, or ‘public thing’.

Such ideas did not cultivate a stable political community. For all Henry VI’s political ineptitude, remaining totally silent through council meetings and reversing the progress of his father’s victory over France at Agincourt, he was renowned for his virtuous piety. A character unfit to lead a nation was therefore able to rule for almost four decades.

To England’s detriment, Henry VI’s weakness allowed ambitious subjects to dominate politics with their personalities. The earl of Warwick was able to rally vast support for a violent rebellion in 1459 by appealing to the idea of the good of the ‘commonweal’, a derivation of Aristotle’s res publica. Such rhetorical appeals underpinned all great rebellions in English history, including the seventeenth-century Civil War which killed more proportionally to the size of the population than did the First World War. Such violence was not what was intended by early critics of Charles I. John Pym, who spearheaded the attack on Charles’s unpopular religious policies, appealed to the idea of the public to legitimise his dissent. As his advocating peace by the time of the war’s outbreak shows, he realised that he had played with fire and had miscalculated the potential impact of his rhetoric. Events outran Pym’s control. Although the rhetoric of the public, or res publica, had not changed, its social makeup had. Information had proliferated, particularly since the growth of Dutch printing presses providing the king’s enemies with a means to spread their message. Pym therefore ignited a more radical and informed political community than he intended.

Pym’s folly is disconcerting in the social media age. It is in a similar, if not the same, vain that candidates have framed their intention to challenge Trump in 2020. Take Kirsten Gillibrand’s Facebook post announcing her candidature. She highlights her inner virtue, “I believe in right versus wrong”, she grafts virtue onto appeals to an abstract ideal of America, a res publica, “an America defined by strength of character, not weakness of ego”, and again on the note of public support with her aim of “restoring power to the people.” Her use of the idea of restoration echoes another medieval political trope. Henry V was considered a great king not for innovation, but for his restoration of an idealised past so was praised as a new Constantine, first Christian Roman Emperor.

I do not doubt Gillibrand’s sincerity, but wish to contextualise her in an unstable political culture that has precipitated insurmountable conflict. Nor do I suggest that 2020 should anticipate a violent clash like that under Henry VI or Charles I. However, we must realise that a rhetorical political culture is dangerous. Ideas of commitment to the res publica are now framed in a discourse on progress. Democrats pursue a Green New Deal in the name of progress, providing a dearly needed solution to a great problem of our age.

Progressive rhetoric has also given the politically disillusioned a framework to legitimise dissent, for it is a derivation of the idea of the res publica. Liberals have been progressing, moving forward. Many feel left behind. Such sentiment, coupled with the explosion of information, jettisoned Trump into office. It also provided the Gilets Jaunes with legitimacy to violently oppose an act in pursuit of the same goals as the Green New Deal, Macron’s fuel tax. Just as under Henry VI or Charles I, abstract ideals have constructed an implosive political culture in which groups compete to graft mutually antagonistic interests onto an ideal of the public good: environmental policies are framed in a discourse that is legitimising opposition to those green endeavours.

John Pym never intended to enable regicide. He intended his rhetoric to encourage more protestant practices, to contribute to the salvation of the public. Aquinas himself would approve of his intent. Intent, however, is not the whole picture. Cheney may be immoral, Gillibrand may be genuine, but overemphasis on virtue and appeals to idealised versions of the public weaken our political communities. America may not be the same place England was in 1649, but the same forces that affected that terrible groan at the sight of a decapitated king are still at work.