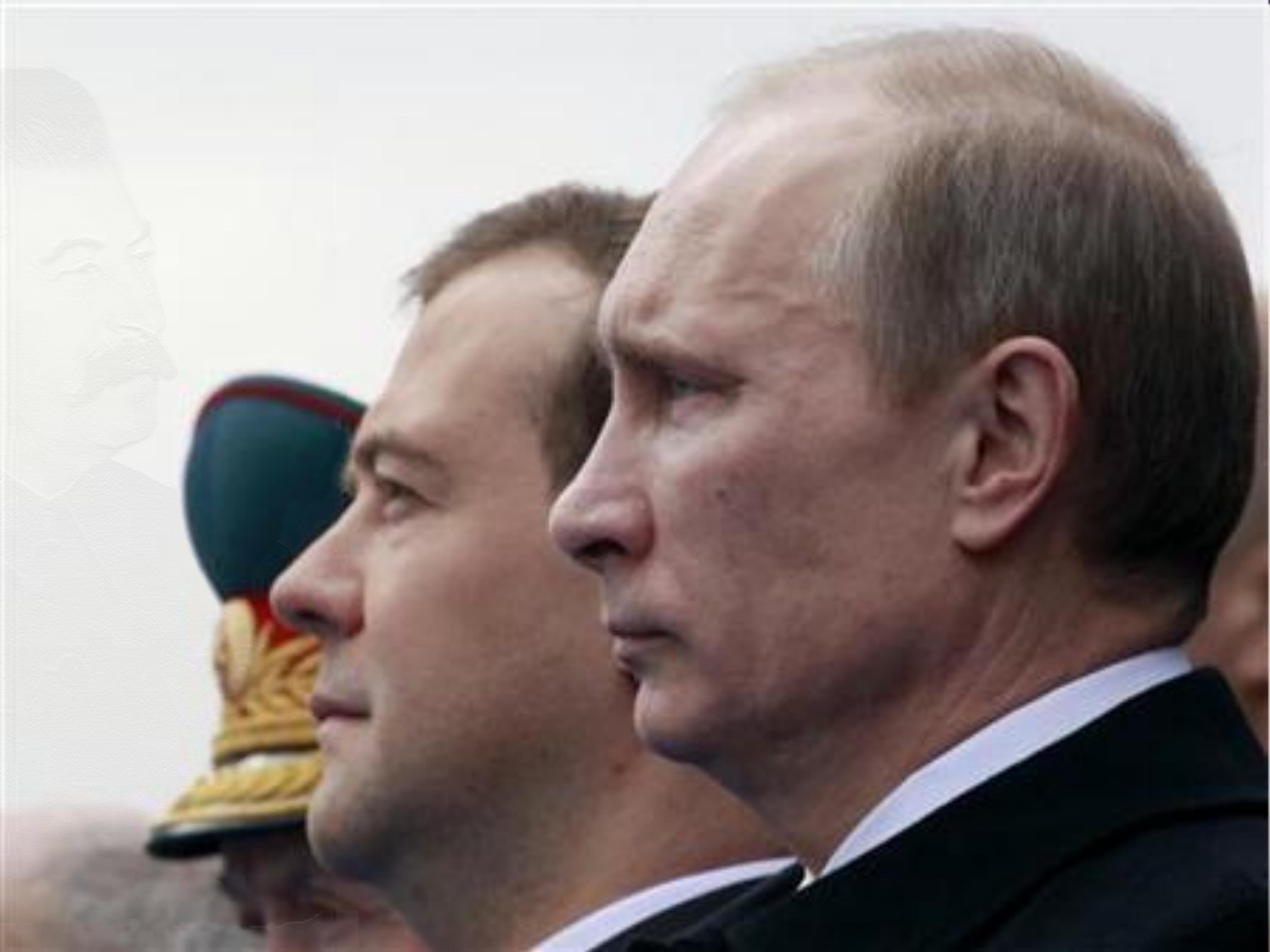

Putin – A hero, a villain, and soon to be a coin…

Sitting at the Tehran Conference in 1943, deciding how Europe was to be carved-up in the post-war world, Winston Churchill summarised proceedings:

“There I sat with the great Russian bear on one side of me with paws outstretched, and, on the other side, the great American buffalo. Between the two sat the poor little English donkey, who was the only one who knew the right way home.”

In 1943, the two great superpowers of the USSR and the USA were clearly emerging as previous European empires began to crumble, brought low by the exigencies of the Second World War. The Grand Alliance to defeat Hitler was but a thinly veiled marriage of convenience which could not hide the unbridgeable differences between the capitalist and communist systems, and consequently the USA and the USSR as their chief proponents. Decades of hostility and animosity, of one-up-manship and flirtations with nuclear annihilation followed as the world split into two distinct camps – you were either with us or against us, a patriot or a traitor. Uncle Joe and Uncle Sam may have been sitting next to one another, but they were worlds apart.

Why is this important? You’re reading this in the politics rather than the history section because, with qualifications, this is the bipolar world Vladimir Putin is seeking to restore.

Recent news that coins are to be minted with the image of Putin’s face beneath the title “The gatherer of the lands” (a reference to Ivan the Terrible, a greatly expansionist Tsar whose moniker “Terrible” is richly deserved) in celebration of Crimea’s annexation are reminiscent of the propaganda ploys and gimmicks that characterised the Soviet Union. And they are not the only recent reminders of a hardening of power and a return to more archetypally Soviet methods. Having refused to hand over the details of Ukrainian protesters using his site, the founder of VKontakte (a Russian equivalent of Facebook enormously popular in Eastern Europe) has been fired, replaced by a Putin crony who, I am sure, will shortly be the subject of Western sanctions. Government sponsored concerts and celebrations are being held to welcome Crimea back into the Russian fold, and Russian news is relentless in its labelling of Ukrainian protesters as violent fascists, hell-bent on killing all but ethnic Ukrainians, and their American allies as interfering puppet-masters, pulling the strings and fomenting chaos and bloodshed.

Let’s not get carried away. Domestically, modern Russia is a temple of consumerism and capitalism. The GUM department store, where for decades Soviet citizens would queue for hours in the hope of being able to buy some bread, is now full of Louis Vuitton, Gucci and Prada – brands flashed around Moscow in the same way Communist insignia perhaps once was. Russia will not, for the foreseeable future, return to communism.

However, such seemingly nostalgic foreign policy rhetoric, conjuring up images of Slavic togetherness and resistance to domination should come as no surprise, for it has been a key tenet of Putin’s platform ever since he came to power in 1999. He has spoken before about how he considers the collapse of the USSR to have been “a major geopolitical disaster” and his intention to restore a bipolar world in which the USA does not call all the shots. This is a popular message in Russia. In many ways the Americans are architects of their own downfall in this regard – their willingness to get involved in conflicts from Iraq to Libya to Ukraine, in areas far outside their traditionally considered sphere of influence, has far from endeared them to a Russian population and some would say the wider world.

Ukraine is, of course, the primus inter pares of these examples. The birthplace of the Russian state, an integral part of Russia throughout much of its history, and a key trading and diplomatic ally. The prospect of them becoming a NATO member is akin to waving a red rag to a bull, or, rather, prodding a sleeping bear. Whilst not justified, the Russian reaction is at least understandable.

However, the Russian reaction also suggests how misleading it is to compare the power of the USA and Russia. Whilst it is my genuine belief that many, and probably even a majority, of Eastern Ukrainians wish to follow Crimea’s lead and become part of Russia, this is largely as a result of historic ties, nostalgia, and the basket case that is the Ukrainian economy. The presence of Russian troops in the region is also, no doubt, a “motivating” factor.

But it has become evident that Russia has very little “soft power”. To achieve her goals she must resort to sending in troops, if not to force proceedings then very much to influence them. American culture is enormously pervasive, the “McDonalds effect” if you will, and with this comes an influence, a means of a affecting and shaping the world. In my experience, foreigners speaking English will, more often than not, do so in an American accent, picked up from watching shows like Friends, Sex and the City, film franchises from The Godfather to Avengers, and musicians from Britney to Bieber. You may think these details irrelevant, but it is worth noting the power of American mass culture in forming the basis of world mass culture. How many thousands of people have died in the pursuit of a US green card? A great deal more than have done so pursuing Russian citizenship, I would venture.

This won’t change events on the ground, not in the short term, and whatever (equally questionable) moral authority the West may seek to claim over events in Ukraine will also have little effect. Having pledged the Ukrainian government enormous support and opportunities for cooperation with European bodies, almost a second Marshall Plan, the West is beholden to deliver on these promises to keep in tact whatever authority and moral decency it can still muster. If such is delivered, it is the position Ukraine finds itself in in twenty-odd years time that is of importance. If she has balanced her books, developed her economy, and generally improved the standard of living, that, surely, will be the greatest demonstrator of the power and progress the West can offer through its soft power in lieu of the Russian jackboots and Kalashnikovs.

Having started with a quotation from Churchill, it seems fitting to end with a retort. Whilst speaking in 1944 about the Pope’s moral influence throughout the world, Churchill found himself interrupted by Stalin as Uncle Joe quipped:

“And how many divisions does the Pope of Rome have?”

Only time will tell what lies in store for the bear, the buffalo, and the donkeys caught in between.