The Goldfinch has been met with much critical and commercial acclaim

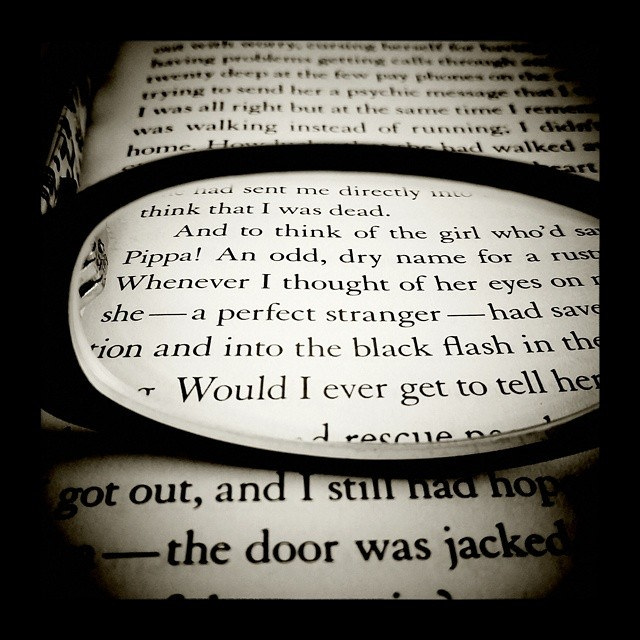

Donna Tartt’s long-awaited new novel The Goldfinch finally arrived last year, quickly becoming one of the most talked-about works of 2013. Part of this must be understood in the context of Tartt as a writer; an enigmatic, fairly reclusive presence on the literary scene, she has written only three novels, taking roughly a decade to work on each of them. Her first and perhaps finest, The Secret History, appeared in 1992, to be followed by The Little Friend in 2002 and now, after much critical hype, The Goldfinch.

The Goldfinch has generally been regarded as a return to form for Tartt, both critically and commercially. She scooped the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for it in 2014, Warner Bros have already bought the film rights, and it has spent 39 weeks and counting on the New York Times bestseller list. More recently, however, the novel has begun to acquire increasingly vocal detractors, and surprised many by not even making the longlist for the Man Booker Prize (more on which later).

Let’s start at the beginning. Openings are something of a Tartt speciality, and this latest is no exception. The novel opens in Amsterdam, with our protagonist, Theo Decker, clearly in some kind of – as yet mysterious – dire straits, holed up in a hotel room scanning Dutch newspapers he cannot understand for mention of his name. Tartt then races backwards to Theo at age thirteen, surviving a bomb blast in New York’s Metropolitan Museum which kills his Mother and bequeaths him a small, incredibly rare Dutch painting – ‘the smallest in the exhibition, and the simplest’.

This painting is ‘The Goldfinch’ by Carel Fabritius, a real work of art which in fact resides in The Hague’s Maritshuis (although it is temporarily resident in The Frick, New York, and is attracting huge numbers of visitors thanks to the success of Tartt’s novel, in a sweet show of life reflecting art). Fabritius was a student of Rembrandt’s, who died prematurely when a gunpowder factory exploded near his studio in Delft, and destroyed the vast bulk of his artwork. The paintings survival of Tartt’s fictional bomb blast is thus a nod to its actual, improbable history. Theo’s Mother states just before she dies that ‘anything we manage to save from history is a miracle’; the painting is testament to that, both in fiction and in reality.

The plot sprawls outwards from this single, life-altering event, encompassing New York antiques dealers and upper-class socialites, an LA populated by gamblers and drug addicts, and the international criminal underbelly of the art world. This is the journey of a motherless boy with no place in particular to go, and no aim other than avoiding social services; as such, the narrative is a stark contrast to The Secret History, which concentrated intensely on a small, closed community.

The novel’s colourful range of characters has drawn several comparisons to Dickens, from the figure of Theo’s kindly old benefactor Hobie to Pippa, the love interest he is utterly obsessed by, to his best friend Boris, a Ukrainian petty criminal and Artful Dodger figure who ‘drank beer the way other kids drank Pepsi, starting pretty much the instant we came home from school’. In contrast to these somewhat larger-than-life figures, Theo’s relationship with his Mother has the distinct, devastating taste of the real; although she is dead by the end of the first chapter, her presence continues to permeate the novel, as ‘a force all her own, a living otherness’. The young Theo’s grief for her is intensely moving, as he grows to realise that ‘every new event – everything I did for the rest of my life – would only separate us more and more […] Every single day for the rest of my life, she would only be further away’.

Aside from this treatment of grief and loss, Tartt is at her most assured in the novel when dealing with drug addiction, and its ‘pure pleasure, aching and bright, far from the tin-can clatter of misery’. In LA, Theo and Boris experiment and experience ‘magical speechless nights where [they walked] into the desert half-delirious at the stars’; LA in her telling is all at once alien, alienating and strangely majestic. Subtle parallels are drawn between this physical form of addiction and the eerie pull of antique objects, with their ‘magic that came from centuries of being touched and used and passed through human hands’. As Hobie puts it, ‘If you care for a thing enough, it takes on a life of its own, doesn’t it?’ We bestow upon our most beloved possessions a power which, as Theo demonstrates, has the potential to lead us dramatically astray.

This said, some critics have argued that the novel is itself offering a mere illusion of artistry. London’s Sunday Times concluded that ‘no amount of straining for high-flown uplift can disguise the fact that The Goldfinch is a turkey.’ Julie Myerson’s review was even more brutal, describing it as a ‘Harry Potter tribute novel’, ‘peopled entirely by Goodies and Baddies’. And it’s not only Brit critics who are now willing to be damning; The New Yorker’s James Wood also bemoaned its similarity to children’s literature, seeing it as a sign of a literary culture which has become increasingly infantilized.

To my mind, the only problematic similarity to Harry Potter is its indulgent length, at 771 pages. The plot can, at times, feel far-fetched or implausible, but this does not prevent it from being gripping, a page-turner which will remind reluctant readers of the kind of pleasure good books can give. It is, in fact, when Tartt strives at the novel’s end for the kind of deep, ‘literary’ thought which might please such critics that the writing, for me, loses its grip on the reader.

Such literary critical debates will only really be settled by the test of time. The Secret History remains as beloved now as it was in 1992; can The Goldfinch prove as lasting? Tartt praises, in her closing pages, the power of beautiful art to ‘[sing] out brilliantly from the wreck of time’, its ability to withstand human corruption and criminality. She celebrates ‘people who have loved beautiful things, and looked out for them, and pulled them from the fire’; it remains to be seen whether The Goldfinch will be one of the works salvaged from the wreckage.

‘