There’s a story to be told about coal mining.

Since the industrial revolution, mining was a huge industry in the UK. At its peak, it employed over a million people – 170,000 in County Durham alone. The UK produced 287 million tonnes of coal from over a thousand pits.

The miners’ strike of 1984 was the largest industrial dispute in British history. The strike went on for a long, bitter year, involved five deaths and over 11,000 arrests, and ended in a decisive victory for Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government. The coal industry was privatised in December 1994, and the last deep-pit mine closed in December 2015. The end of mining in the UK coincided with the collapse of other heavy industry such as steel, shipbuilding, and so on. Former mining areas are now some of the poorest nationally.

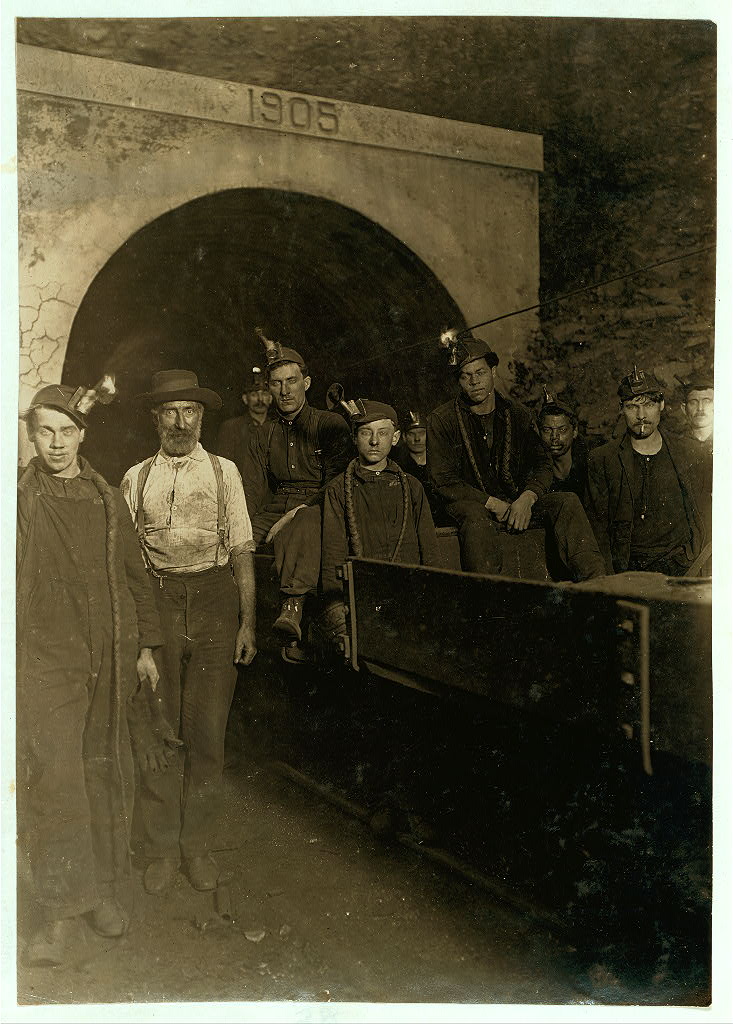

Miners in the early twentieth century. Image available on Flickr under Creative Commons 2.0 license.

So yes, there’s a story to be told about coal mining, but it’s a rather different story that appeared in Nature Human Behaviour a few weeks ago. Geneticist Abdel Abdellaoui has found, via inspection of genomes of people living in former mining areas, that they contain genetic signatures associated with spending fewer years at school and possessing a lower socio-economic status.

Abdellaoui’s research represents an advancement in the field of social genomics, the field of research that examines why and how social factors affect the activity of the genome. It’s an interesting area of research, to say the least; when newspapers print articles about genes for smoking, or criminal behaviour, or sexuality, it’s social genomics they’re referencing. The debate that continues to rage over “nature vs. nurture” – or, the relative impact of environment vs. genetics in determining phenotype – is in itself effectively social genomics.

Unsurprisingly, the field is contentious. It’s been argued that sociogenomics is opening a new gateway to eugenics: that’s not so difficult to believe. There’s an obvious massive potential for exploitation of the knowledge that a controversial genetic marker like intelligence varies between race, or sex, or class. Science doesn’t exist in a moral vacuum: no knowledge is exempt from being used and abused. There’s a question to be raised as to whether such contentious markers should be studied at all, even though it will get you published in Nature.

Nonetheless, Abdellaoui’s research is actually more nuanced than the headlines would have you believe. People who were born in one of these post-mining communities but later left actually had higher educational attainment scores than the national average. This leaves the remaining people in the community with a lower than average score. This isn’t a story about people in post-mining areas having lower intelligence markers; this is a story about educated people leaving the post-industrial north.

There’s a huge gulf between the post-industrial north and the more affluent areas of the country, and it’s a gulf that’s only widening. Genetic markers of deprivation are just a new detail to couple with the sharply lower employment rate, the lack of highly-skilled jobs, even the lower life expectancy. In this context, it’s not surprising that educated people are moving away. Whilst sociogenomics might add a new spin, this is a tale as old as time.