My name is David Harris, and I’m a second year Natural Sciences student at Van Mildert. I’m also the Director of Music at St Oswald’s Parish Church, where I play the organ and conduct the choir. I consider my knowledge of classical music to be pretty good: I know the years of J.S. Bach’s birth and death (a vital piece of trivia for any organist), I can play the Chopin Nocturne used in season nine, episode five of How I Met Your Mother (it’s in E flat major, op.9 no.2), and I can most definitely tell my Arne from my Elgar. But I don’t know enough about popular music.

I was never really exposed to anything other than Classic FM in my youth. This was, and remains, my mother’s radio station of choice. It was played in the kitchen, in the car on the way to school, and in my bedroom as I slept (although it was later replaced here by Harry Potter audio books read by Stephen Fry). I learnt the piano, and eventually the organ, at school, but I was still stuck firmly to classical; I barely even ventured into jazz. Scott Joplin was about as modern as it got for me.

Eventually, during my early teenage years, I realised that listening to popular music was essential to being popular at school. After this epiphany, I had some small success at both. My choice of music was mostly influenced by my friends and my older sister, who had caught on considerably earlier than I did. It is a point of no small amount of pride to me that she now borrows my CDs.

However, my repertoire is still severely limited. There is little chance I’ll have heard of a group or their music if they are not performing today (and even then, the odds are still fairly slim). I play it safe, listening only to what I know I will like. I don’t listen to the radio, and even treat the ‘related artists’ sections on Spotify and iTunes with a certain amount of apprehension. My awareness of popular music, the richness of its history, and the variety of its genres is non-existent next to my acquaintance with the classical world. I am truly awful at the Intros round on Never Mind The Buzzcocks.

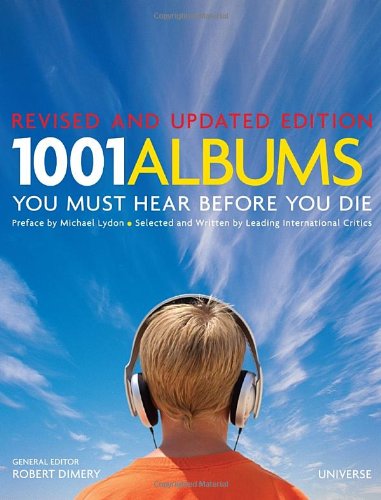

In order to rectify this, I have purchased a book entitled 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. I intend to listen to every album in the book by picking random numbers between 1 and 1001, and until the Music Editor of The Bubble gets bored or I leave Durham, I will send him regular field notes, chronicling my musical exploration: what I have learned from a particular album as I delve into it head-first with book in hand and several Wikipedia tabs open. My favourite tracks from each album will go in a Spotify playlist, already started here: 1001 Albums To Hear Before You Die.

And eventually, I will be able to hold an educated conversation about popular music.

The phrase “one of The Beatles’ most influential albums” is comparable to “one of the highest peak in the Himalayas.” Dealing with something towards the higher end of a spectrum whose low point is 6,638m above sea level is not to be taken lightly. So it is with Sgt. Pepper, an album of such colossal importance that even I have it on my iPod, and an ideal starting point for this musical exploration.

In any medium, critical and commercial success do not always go hand-in-hand, but the response following the album’s worldwide release on June 1st, 1967, was emphatic in both areas. For the following fifteen weeks, it occupied the number one slot in both UK and US album charts, and stayed there in Britain for a further seven. It enjoyed further success at the 1968 Grammy Awards, winning Best Album Cover, Best Engineered Recording (Non-Classical), Best Contemporary Album, and Album of the Year.

It isn’t often, either, that an album release receives such widespread attention. Langdon Winner wrote that the album constituted “the closest Western Civilization has come to unity since the Congress of Vienna in 1815,” describing its popularity in “every city in Europe and America.” It was played on radio stations everywhere, often in its entirety. Elsewhere it was described as “a historic departure in the history of music – any music” (Time magazine) and a “masterpiece” (Newsweek). Retrospectively, Sgt. Pepper has continued to receive great acclaim: it still holds the top slot on Rolling Stone magazine’s list of the Greatest Albums of All Time.

But praise was not universal. Richard Goldstein, writing in the New York Times, wrote that “like an overattended child, this album is spoiled. It reeks of horns and harps, harmonica quartets, assorted animal noises, and a 41-piece orchestra.” Later in the review, he said, “[t]he obsession with production, coupled with a surprising shoddiness in composition, permeates the entire album,” followed by the most damning sentence of the piece: “There is nothing beautiful on Sgt. Pepper.”

What followed was a backlash so strong that Goldstein was forced to pen a defence of his criticisms less than two months later. But in more recent times, many critics have forgiven him – even come to agree with him. In 1981, notable music journalist Lester Bangs declared that “Goldstein was right in his much-vilified review… predicting that this record had the power to almost singlehandedly destroy rock and roll.” The problem, for many, is summed up in Bob Dylan’s reaction on hearing the album for the first time in Paul McCartney’s hotel room: “Oh, I get it. You don’t want to be cute anymore.” The Beatles had decided that aside from good music, they wanted to pursue something far more ambitious: artistic credibility.

Whilst George Martin, the album’s producer, protested in 1990 that “The Beatles themselves never pretended they were creating art with Sgt. Pepper… they just wanted to do something different,” it is rightly regarded as one of the first ever art rock albums. It made album art a credible form of expression, its lyrics were compared to the work of T.S. Eliot, and its music drew extensively from classical influences, including orchestral arrangements and the album’s loosely-unified structure – more like a symphony or a suite than anything that had come before in popular music. It is also called the first concept album, with its tracks linked by over-arching themes and the narrative of the Lonely Hearts Club Band themselves. But not everyone agreed that rock music should be an art form, and the sub-genre’s influence was fairly short lived; it had petered out by the end of the seventies, although strands of it have continued through artists such as Queen, David Bowie, and even Radiohead.

The songs themselves showcase the Beatles’ superb innovation and versatility. For the latter, you only have to look to the Indian influences of Within You Without You followed immediately by the Formby-esque style and classically-arranged clarinets of When I’m Sixty-Four, coupled with the slightly more conventional songs on the album. It has a near-unprecedented level of production effects, contributing to the general aura of psychedelia; McCartney later described it as a “drug album.”

The track that sticks out like a sore thumb, for me, is Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite!. There is a fine line between experimental and off-putting, and I think this song is just on the wrong side of it. But the reason that it is a negative point that stands out is that the rest of the album is a musical triumph. A Day In The Life is beautiful and harrowing, using sparse arrangements to great effect. The accompaniment for She’s Leaving Home represents – quite literally – several more strings to the quartet’s bow, performed as it is by a ten-part ensemble of violins, violas, cellos, double bass, and harp. Melody, harmony, and lyricism are combined magnificently, particularly in With A Little Help From My Friends.

Sadly, these tracks can’t go on the Spotify playlist (available here), because the album isn’t available. But they certainly deserve a place there, along with the vast majority of the accolades and hyperboles the album has attracted since 1967.