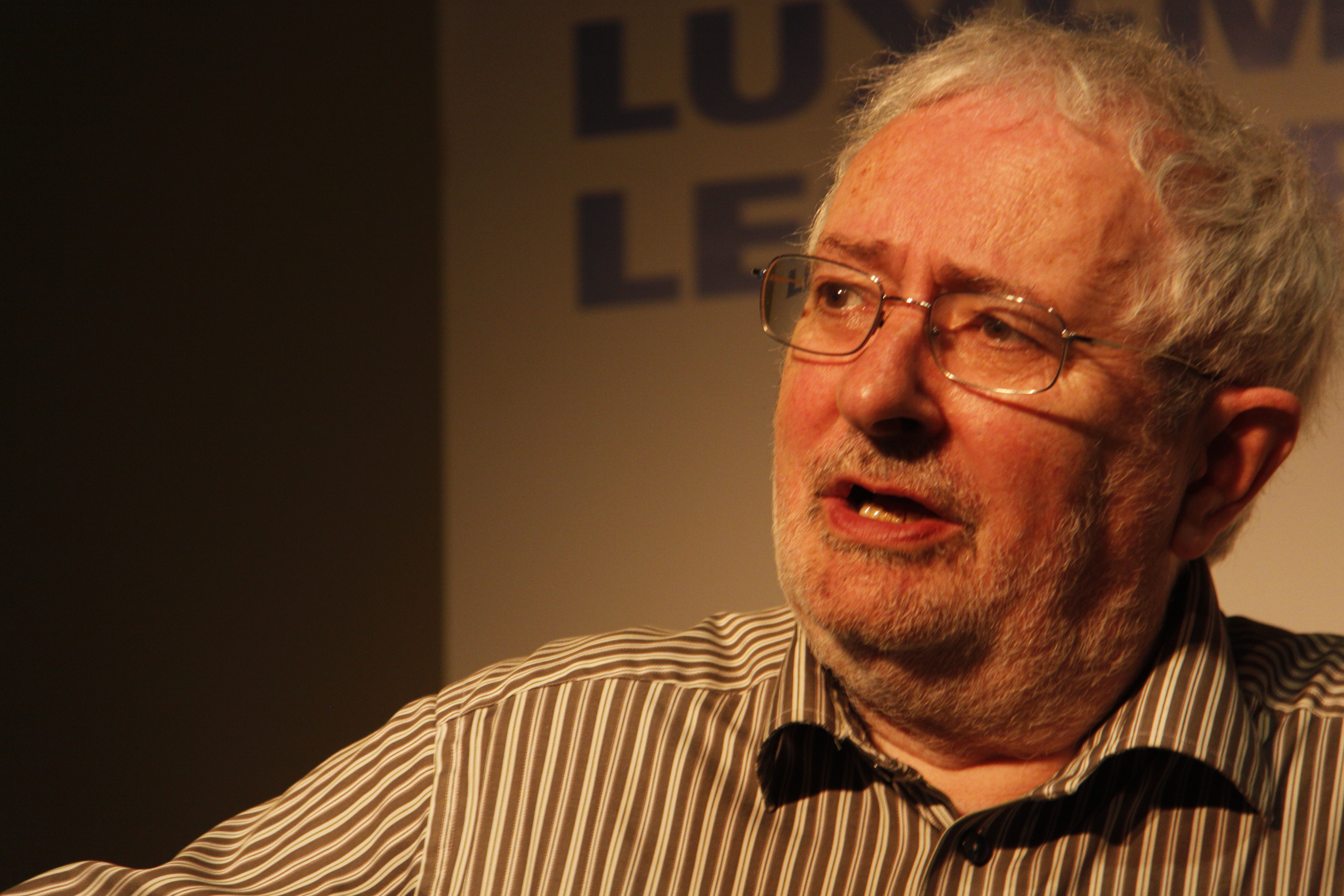

English writer, critic and literary scholar, Terry Eagleton spoke at the Hatfield College Lecture this month

This is Nietzsche’s clarion call in the ‘Parable of the Madman’:

‘God is dead.

God remains dead.

We have killed him.’

Since then, ‘the Death of God’ has been a popular catchphrase that celebrates humanity’s liberation from the working hypothesis of God. There have been attempts to cement the notion that the world no longer needs God (e.g. Dawkins’ ‘The God Delusion’), thanks to recent efforts by the New Atheists.

However, Prof. Terry Eagleton, who spoke at this term’s Hatfield College Lecture, argues that ‘history is littered with the rubble of surrogates of the Almighty’. He further argues that it would be a very tall order for a whole civilisation to achieve atheism. Hence, Nietzsche’s prediction took decades and countless failures to see a measure of fruition.

Prof. Eagleton argues that it is advanced capitalism – humanity’s drive towards wealth and our increasing obsession (though we may adamantly deny it) with materialism – that has dug ‘God’s grave’. Simply put, the financial market, economics and CEOs have built a golden statue and little idols for men to worship and show devotion.

It is in this era where grand narratives are no longer needed, where we are told that belief is something we can chuck away or accept according to our whims and fancies, that a ‘faithless capitalist society’ is born. ‘Faithless’ in this sense is not the absence of belief (certainly everybody has a belief system whether they are conscious or unconscious of it), it is rather a rejection of religious truth claims of a Transcendental Being that is the rightful ruler of the cosmos.

Prof. Eagleton argues that this is the direction in which humanity is headed – increased secularisation and consumerism, and this is the system that surpasses all other cultural attempts at displacing God. However, for all the development of Western civilisation, there is a minority that has lagged behind. This minority is now living in the shadow of Western post-Cold War triumphalism and so they want to break free, to make themselves known – thus the birth of religious fundamentalism. Prof. Eagleton sees anxiety as its source. It is insecurity in the face of the West’s brutal capitalism that give rise to men and women who staunchly and sometimes violently hold on to beliefs that seem to be antediluvian. Ironic then that the West seeks to kill its bastard son, whereas the son seeks to reciprocate his ‘father’s’ affection – reminds me of Freud with a twist.

However, Prof. Eagleton might be mistaken in setting out the fundamentalists (those who believe too much) and the faithless (CEOs and capitalists) as the only two opposing poles. It is, I think, a false dichotomy to merely divide the world into these two camps. If Prof. Eagleton is addressing religion (fundamentalism) as an institution and nothing more, then I would greatly disagree with his diagnosis of current world affairs and his prognosis of what the future has in store. There is at least one other camp that leans towards neither ends of the spectrum.

So, before we boldly start telling people that God is dead and exult in the greatest murder of history, there is a need to understand the extent of that claim.

Nietzsche did not merely proclaim that God is dead, he was cognisant of the immensity of the ramifications.

How could we drink up the sea?

Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon?

What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun?

The world also becomes directionless, where men and women meander through life as though floating in a dream.

Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving?

Away from all suns?

Are we not plunging continually?

Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions?

Is there still any up or down?

Are we not straying, as through an infinite nothing?

Nietzsche warns:

Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us?

Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?

This warning cannot be ignored. This is either pleasing or sombre news: we cannot simply flow with the current of the zeitgeist without knowing the direction it is heading.

Steve Turner, in the post-script of his poem ‘Creed’ presents a shocking conclusion of God’s death:

If chance be the Father of all flesh,

Disaster is his rainbow in the sky,

And when you hear

State of Emergency!

Sniper Kills Ten!

Troops on Rampage!

Whites go Looting!

Bomb Blasts School!

It is but the sound of man worshipping his maker.

Hence, whatever form advanced capitalism chooses to adopt: consumerism or materialism, and whatever its effects, it is mere man worshipping himself.

So, is God dead? Will the War on Terror stop?

I’m not sure of your conclusions, but I sincerely believe that He isn’t dead – we still need Him to save us from self-destruction; yes it will end, as all things reach their denouement according to their fixed times.

What then does it mean for the 21st Century Man?

A choice has to be made – institutionalised religiosity or structured materialism? No, popularised idiosyncratic ‘spiritualism’ isn’t any better – it is the product of postmodern culture. Prof. Eagleton argues ‘culture doesn’t go all the way down… the elements of culture are double-edged swords that do both good and harm’.

What then grants us the foundation to live and move and have our being, since we need that focal point?

Ecce Homo – behold Jesus on the cross where God did die that we might live.