TW: rape and sexual violence

Monday 25th November marked the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. The United Nations General Assembly designated this day to bring awareness to gender inequality, and the systematic and pervasive forms of violence that come from it. UN senior officials use this day to show their solidarity with survivors of gendered violence, and to voice their support for activists working for equality.

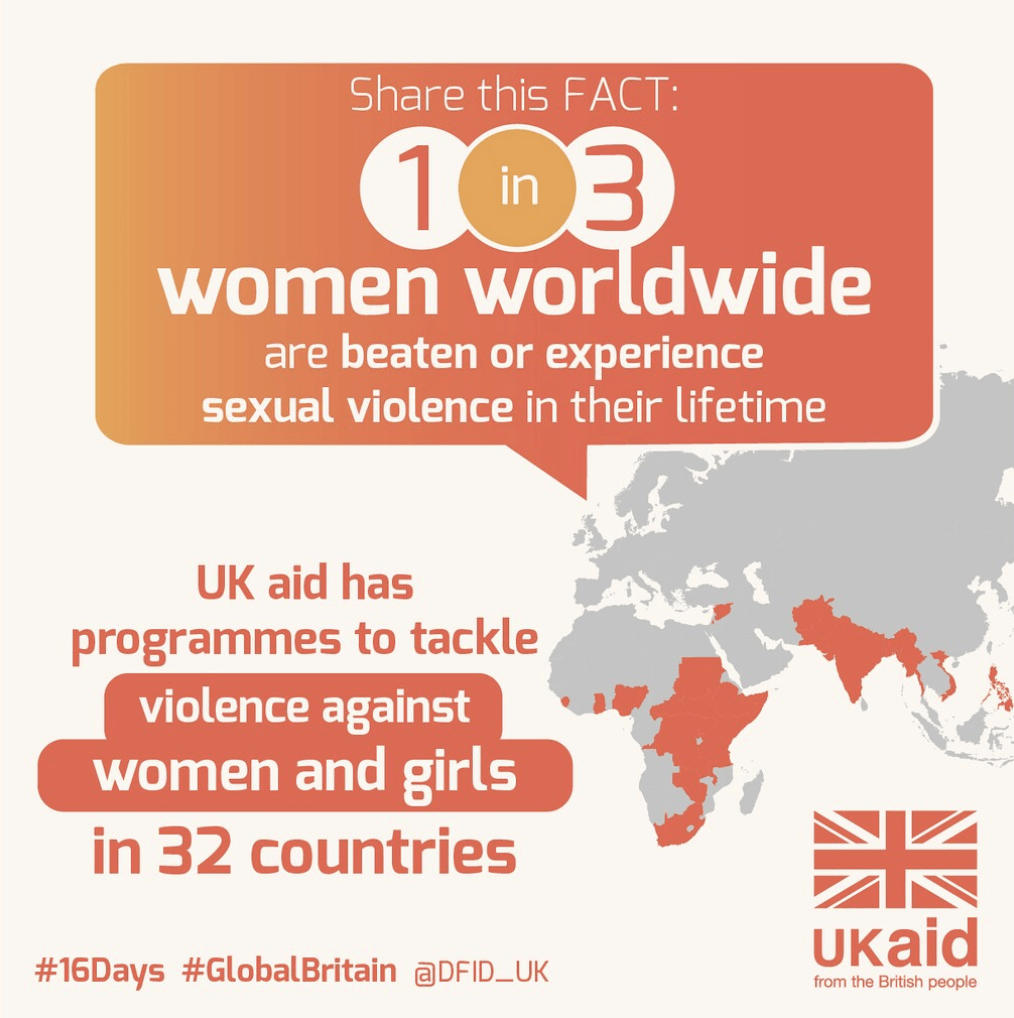

The Secretary-General, António Guterres, stated that ‘violence & abuse against women are among the world’s most horrific human rights violations, affecting 1 in every 3 women in the world’, adding that ‘we must take a firm stand against sexual violence’. Guterres highlighted that sexual violence is ‘rooted in centuries of male domination’, bringing to the fore the fact that rape culture is a result of gender discrimination and misogyny. Rape and sexual assault cannot be seen as something separate to the patriarchal society in which the male voice dominates the public and political sectors. It is in fact because of this power imbalance that such human rights violations are carried out.

Image by DFID. Available on Flickr under Creative Commons 2.0 licence

Guterres warned that ‘rape is still being used as a horrendous weapon of war’, which echoes the joint UN-Red Cross appeal to end the rising use of sexual violence as a war tactic. As part of this appeal, President of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Peter Maurer, stated that the ‘we continue to face failures of behaviour and accountability’ when condemning sexual violence as violations of international humanitarian law.

The mention of this issue raises an important point. Why is it that sexual violence is constantly underrepresented as a way in which those in power weaponize their control? This form of domination via the denial of one’s own bodily autonomy can be seen to affect the victim’s faction (be it as part of a civil war, international conflict, or other hostile engagement); and the larger group of women as a whole. Rape must be seen as a tactic in war. Scholar Ruth Surfeit criticises the common view that rape is a regrettable aspect of the breakdown of society within wartime, and instead argues that rape should be viewed as a routine and persistent element of military strategy. Sexual violence can, in this way, be used as an instrument of war which undermines the will and cohesion of the enemy population.

Rebecca Whisnant, the director of the Women’s and Gender Studies Program at the University of Dayton, argues that ‘because rape in war frequently seeks to undermine and destroy bonds of family, community, and culture, there are important points of connection between rape in war and genocidal rape’. One need only look at horrific cases of rape within conflict throughout history in order to see the truth of this claim. Whisnant uses the example of the notorious systematic gendered violence and forced impregnation seen in the Bosnian War, against Croatian and Muslim women. The New York Times reported that a team of European Community investigators estimated that 20,000 Muslim women had been raped by Bosnian Serb soldiers, as part of ‘a deliberate pattern of abuse’ which aimed to drive them away from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Their report stated that ‘rape cannot be seen as incidental to the main purpose of the aggression but as serving a strategic purpose in itself’, noting that rape was used to demoralise and terrorise communities. As a result of these accusations, the first ever UN tribunal involving charges of sexual violence took place in 1997 in which Duško Tadić was found guilty of violating the laws and customs of war and crimes against humanity.

Duško Tadić at UN tribunal

Image by UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Available on Flickr under Creative Commons 2.0 licence

Although this landmark case is a huge step forward in holding perpetrators of sexual violence accountable for their actions, it again brings up the question why it took until 1997 for rape and sexual assault to be understood as the violent war tactic that they are. Although I cannot pretend to answer such a huge question, I will suggest that the answer lies somewhere within the patriarchal control of society. By way of elaborating what I mean by this, I will refer to the feminist international law scholars Hilary Charlesworth, Christine Chinkin and Shelley Wright who argue that international law operates in a ‘masculine world’. Sectors of society, and as a consequence, the resulting law that codifies it, are separated into the political, public domain, and private, domestic domain. These different spheres are imbued with gendered stereotypes, as the political sphere is seen as being a man’s world as opposed to the woman’s place in the home. There is a ‘public/private dichotomy based on gender’, which is perpetuated by the domination of the ‘male voice in all areas of power and autonomy in the western liberal tradition’.

From this, it appears to be the case that all things to do with sex, reproduction, and motherhood are in the private sphere as opposed to those violent “masculine” deeds of violence and war. If such a dichotomy is engrained within our society, as I suggest it is, then encountering an act that combines elements of both spheres is very difficult to comprehend. Events are seen to be either in the home or on the political battlefield, not both, and this causes a problem when we propose that rape and sexual assault is an act of violence as part of a political agenda, that occurs in the domestic setting. It is therefore necessary that we shatter this distinction between the two spheres of life. Just as we should no longer view men and women as having separate places within society, so should we put a stop to the common view that domestic actions and political tactics cannot be inextricably intertwined.

Although the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women has passed, let us continue to fight against inequality, sexual discrimination and gendered violence. We must recognise rape and sexual assault for what it really is, that is forms of violence, and hopefully our justice systems will start to treat it as such as a result.

Featured image by United States Mission Geneva. Available on Flickr under Creative Commons 2.0 licence.