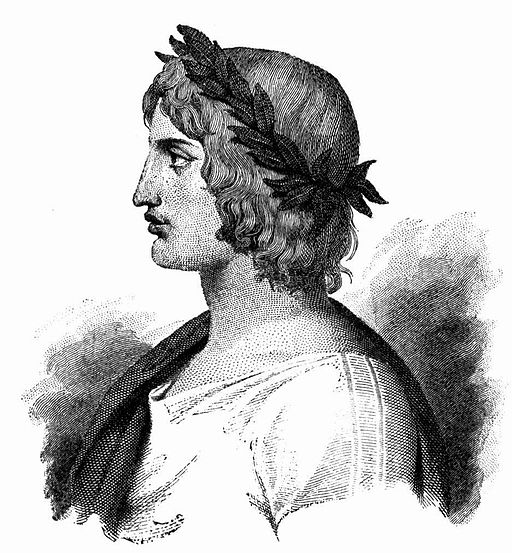

The poet Virgil, who was commissioned to write the Aeneid in 29BC

Historical literature has been around for almost as long as the discipline of history itself. When Augustus Caesar commissioned the poet Virgil to pen the Aeneid in 29BC, its intention was to simultaneously legitimise the rule of the Julio-Claudian family as well as rekindle traditional values by appealing to the pride of Roman citizens. Modern historical literature, however, has perhaps a less obvious attraction for the 21st century history enthusiast. In order to answer the question of its usefulness as a historical tool, however, a distinction must be drawn between such a ‘history enthusiast’ and a more formal student of history, for although many identify as both, these roles perhaps define ‘historical usefulness’ in different ways.

A case could be made to a certain extent, that even 21st century historical literature has some use to the student of history, insofar as it provides a general and intuitive feel for a historical period, without dealing too much in specifics. This is however, subject to the quality of research put into the work in question, and it is at this point that a more precise definition of historical literature might be considered. The term ‘historical literature’ implicitly suggests a certain level of historical scholarship and accuracy, and so we might therefore claim there is at least some inherent value in such work for the student of history. ‘The Wolf Hall’ series, by Hilary Mantel, can perhaps be seen as an example of a happy marriage between historical scholarship and successful novel. This is epitomised by the painstaking effort taken by Mantel over five years to match up even the minutest details of her novels with the historical record. It is not necessarily, however, in such factual accuracy that ‘The Wolf Hall’ series has its value for the student of history; it may instead lie, in the implicit historical thesis that underwrites her work. This is most striking in her characterisation of Thomas Cromwell as a skilled and pragmatic man, who did his utmost to serve king and country in an increasingly volatile political atmosphere. Such a portrait of Cromwell serves to portray him as a product of historical circumstance, whose political skill and opportunism allowed him to navigate for eight years through political and religious upheaval. This offers a differing, yet still accessible, interpretation to perhaps more traditional historical analyses of Cromwell. It could therefore be argued that such a work of literature may open up broader historical perspectives to the student of history.

History students – as distinguished from history ‘enthusiasts’ – should nevertheless be wary of to what degree they can rely on contemporary fiction in order to formulate their own historical ideas and conclusions. This is evidently the case with regards to historical literature that is not the product of meticulous research, but a point that is pertinent to even the work of Hilary Mantel, who in terms of effort put into historical research, is the exception rather than the rule. This is rooted fundamentally in the fact that the primary purposes of historical literature are to entertain and to sell novels. However well researched such a novel may be, therefore, its characters, its dialogue and overall structure are all geared towards this aim, rather than the enlightenment of the under-prepared history student. David Starkey recently claimed rather bluntly that “the idea that historical novelists have any historical authority is ludicrous”. Although these are strong words, the sentiment behind them has some justifiable foundation; the relationship between historical accuracy and the aims of a historical novelist is a tangential one at best.

Novelists that delve into the field of history generally seek to reconstruct a world that will appeal most to modern readership (a readership that encompasses literature as well as history enthusiasts), and so may have a propensity to romanticise and ‘right-size’ the world that they are portraying, which at times may directly conflict with the aims of the history student. Numerous examples of this can be seen in Philippa Gregory’s successful novel ‘The Other Boleyn Girl’; with certain liberties regarding the relative ages of the Boleyn children, as well the sexual deviancy of George Boleyn being taken. In light of these differing aims, as well as in popular readership of such novels, ‘good’ literature is furthermore judged upon its literary quality, rather than any links or claims it might make to historical accuracy. While certain historical novels might provide an introduction to new historical perspectives on a given era, the fact that their purpose is to primarily entertain rather than enlighten (unlike works of actual history), means that their work may reflect modern literary trends and interests rather than the realities of contemporary society that history students strive to reconstruct.

Philippa Gregory once stated that “all history is historical fiction”. While there is certain merit to this statement with regards to the difficulties facing the historian, the implicit – albeit tongue-in-cheek – allusion that the novelist’s version of history can be compared to that of the professional historian is simply not true. While historical literature can in certain instances provide an overall feel for a historical period, and open up new ways of thinking to the history student, this is very much dependant on the work in question. As the work of Philippa Gregory herself demonstrates, there is no necessary correlation between good literature and historical accuracy, and the history student should bear this in mind.

The student of history should therefore use such literature as a useful tool both sparingly and cautiously. For while the function of historical literature has arguably changed significantly since 29 BC, literary authors in reality have just as little obligation to historical accuracy as Virgil did with the Aeneid.