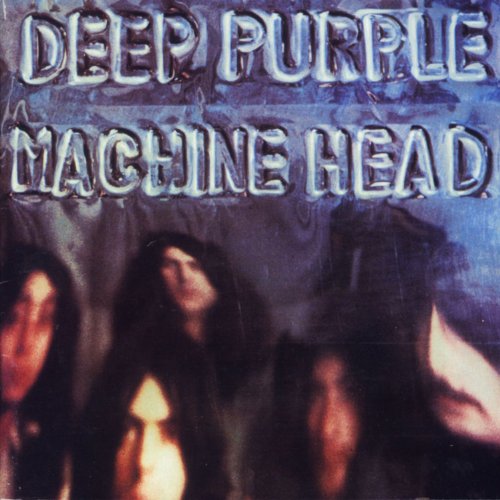

Deep Purple’s Machine Head

For many, one of the greatest injustices in popular music is the omission of Deep Purple from the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland, Ohio. The museum seeks to archive those individuals and groups who have affected and influenced the music industry, and despite Deep Purple being nominated for induction in 2012 and 2013, gaining 2nd place in the public’s vote each year, they have been twice snubbed by the Rock Hall committee. This has rankled with many of their fellow artists, including Toto guitarist Steve Lukather, Guns N’ Roses guitarist Slash, and Metallica’s Lars Ulrich and Kirk Hammett.

Along with Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, Deep Purple pioneered the hard rock and heavy metal scene in Britain in the early seventies; the three groups are often referred to as the “holy (or unholy) trinity” of the genre. Metallica, Queen, Aerosmith, Bon Jovi, Motörhead, and Iron Maiden, among many others, all cite Deep Purple as an influence, and they were ranked at number 22 in VH1’s 2000 list of the “100 Greatest Artists of Hard Rock.”

Perhaps their biggest contribution to musical history, however, is the fifth track of Machine Head. Smoke on the Water contains the Für Elise of guitar riffs; virtually every beginning guitarist learns it, and despite its simplicity, its catchiness earns it the number 4 spot on Total Guitar magazine’s list of the greatest guitar riffs of all time, behind only Sweet Child O’ Mine, Smells Like Teen Spirit, and Whole Lotta Love. (Unlike Für Elise, however, it is actually a good piece of music.)

The track was inspired by real events surrounding the recording of the anthem. The band had intended to record the anthem at the Montreux Casion in Switzerland, where the band had performed the previous year. They arrived there on the 3rd December, the day before the final concert of the season, after which the Casino would close for refurbishments, as it did annually over the winter. However, during the 4th December Frank Zappa concert, an audience member fired a flare gun into the roof of the building, and it burned to the ground. The “smoke on the water” refers to the smoke from the fire spreading over Lake Geneva, which the members of Deep Purple watched from their hotel room.

Eventually, the band settled into recording at the nearby empty Grand Hotel on the edge of Montreux, using a mobile recording unit owned by the Rolling Stones. The unit was parked outside in the snow, but because of the expanses of recording and sound-insulating equipment they had set up in the corridor in which they were recording, they quickly gave up on going outside to listen to the playbacks of their recordings.

The Grand Hotel was only used, however, after they had tried another nearby theatre called the Pavillion, from which they were evicted due to the number of noise complaints received by the police from local residents. Indeed, in 1975, the band was listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as “the globe’s loudest band;” at a concert at the London Rainbow, they reached 117dB, rendering three audience members unconscious.

It is suitably difficult to imagine any of the music on this album being played quietly. Highway Star is a brilliant album opener, showcasing the band’s intensity and virtuosity. The solos of guitarist Ritchie Blackmore and organist Jon Lord are truly incredible – the chord progressions during the duel between the two are reportedly inspired by the compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach. Ian Gillan’s vocals complete the track’s powerful impression, and they are also excellent on Space Truckin’, which proves, with its fantastical sci-fi lyrics, that even metal bands have a whimsical side. Not that it is any less energetic; Ian Paice’s drumming is particularly forceful here.

Machine Head was well-received at its release, gaining favourable reviews and spending two weeks at the top of the British charts. But it seems that their music isn’t considered particularly accessible by those without a specific interest in the genre; whilst Ozzy Osbourne cites it as one of his ten favourite records in an Observer Music Monthly article, its general appeal seems limited. Lester Bangs suggested in 1972 that the band’s questionably pretentious past was also to some extent to blame. But this is an exceptionally good album in its own right, and to my mind, deserves a wider audience.

Four out of its seven tracks made it on to my Spotify playlist accompanying this series, which you can listen to here.