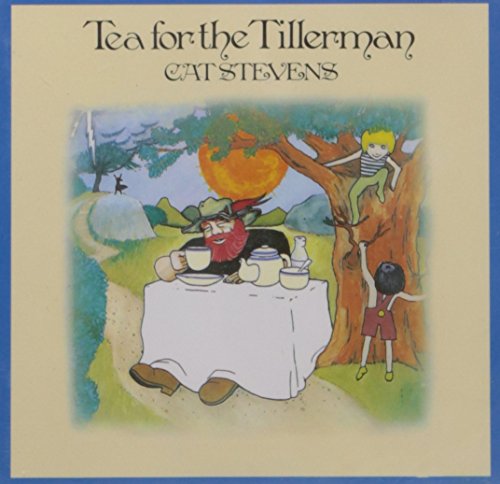

Cat Steven’s Tea for the Tillerman

This fourth album of Cat Stevens (born Steven Demetre Georgiou, now known as Yusuf Islam) is, more than any other album I have listened to as part of this series, a lesson in context. It should not come as a surprise that the events going on in an artist’s life can have an effect on their creative output; but it is seldom more evident than on Tillerman.

Born in London in 1948, and starting his musical career in 1966, Georgiou adopted the stage name Cat Stevens as a more memorable alternative to his given name; in an interview with Salon in 1999, he said that “[he] couldn’t imagine anyone going to the record store and asking for ‘that Steven Demetre Georgiou album’.” Being altogether unsure of how to pronounce his surname, I cannot help but agree. He had a moderately successful early career, impressing manager Mike Hurst (formerly of The Springfields), and gaining fans through the pirate radio station Wonderful Radio London, as well as touring with artists from Jimi Hendrix to Engelbert Humperdinck.

Then, in 1969, he contracted tuberculosis. This came close to being the end of his story; he spent months recuperating in the King Edward VII Hospital in West Sussex, and it took him a year after leaving the hospital to fully recover. It was this that brought him an entirely new perspective on life, and indeed death, the latter of which is particularly evident on his first 1970 album, Mona Bone Jakon.

Tillerman is his second album that year, and whilst he had previously achieved sporadic chart success in the UK, this record earned him a global audience. The advance single, Wild World, came close to being Stevens’ first top 10 single in America, but he had to settle for a nonetheless respectable number 11 spot. The album, released a couple of months later, hit number 8. It sold 500,000 copies within six months, earning it a gold record status in both the UK and the US.

Stevens had by this point escaped from his contract with Deram Records (a sub-label of Decca), as he wanted to pursue a sound with far less production and orchestration than was afforded to him by Mike Hurst. Chris Blackwell, of Island Records, offered him much more creative license, and he certainly took advantage of that. On Tillerman, he retains the same intimate group of musicians – Alun Davies on guitar, Harvey Burns on drums, and John Ryan on bass – to create the folk-rock sound he was aiming for.

Many songs on this, and later albums, were written during his recovery period, where he found himself questioning every aspect of his life and spirituality. He took up meditation and yoga during this period, and became a vegetarian. He also read extensively about world religions – and in 1977, became a Muslim, changing his name to Yusuf Islam a year later. Wild World and Father and Son are particularly poignant in their discussions of the search for spiritual values in a world that hardly values them; the latter containing the line that struck me hardest in the whole album: “For you will still be here tomorrow but your dreams may not.”

Ben Gerson, writing for Rolling Stone in a contemporary review, criticised Stevens for displaying a lack of technical ability in his instrumental playing, as well as placing too much reliance on “dynamics for dramatic effect.” But even these naïve qualities have a certain charm, he says; and Stevens’ sound certainly is charming. His hushed but beautifully clear tone demands to be listened to – not at all in a violent, aggressive, way; rather, it its quiet insistence makes you want to pay attention.

Whilst not displaying anything particularly innovative or groundbreaking, this is a brilliantly-written album. Stevens portrays the internal struggles he has been through perfectly, translating feeling to sound with no loss of meaning. The result is a quietly stunning listen throughout, and an album that displays an incredible amount of natural musical talent.

Four tracks from the album have found their way on to my Spotify playlist, available here, of my favourite songs I’ve encountered in writing this series.