The Who’s ‘Who’s Next’

Who’s Next is The Who’s best-selling album, and to many people, including the band’s guitarist and songwriter Pete Townshend, it is also the finest of the bunch. But it could have had a very different life indeed. Their previous album, Tommy, was released in May 1969; Tommy was a rock opera telling the story about a boy who is deaf, dumb and blind. And it was a hit. Robert Christgau called it the “first successful extended work in rock.” Townshend started work on the follow-up, Lifehouse, drawing inspiration from Indian spiritualists and philosophers such as Inayat Khan and Meher Baba. But it was eventually scrapped, essentially because no-one, bar the author, could understand it.

It wasn’t an entirely worthless enterprise, however; The Who would revisit Lifehouse in various guises over the years. And whilst it led Townshend to the verge of a nervous breakdown and caused many disputes and fallouts within the band (already notorious for having, at times, a less-than-comfortable working relationship, to say the least), producer Glyn Johns recognised the musical potential of the project, and convinced the band to put out a simple studio album. Lucky he did; the album contains some of the most powerful hard rock anthems ever written.

And for many, Next is simply more authentic than the rock operas – the nevertheless successful Tommy and whatever Lighthouse might have been. Those were about ideas, and complex ones at that; grand narratives inspired by mysticism and spiritualism woven intricately into the space of a single album. But, to some extent, overthought. Next is not without its pretensions; but it takes the concepts back to a simpler, more emotionally intimate level, without losing any of their impact.

It’s an album of extremes. Entwistle’s bass lines are utterly frenzied; if any modern drummer played like Moon does on this album, they would be told to rein it in. (And this is relatively restrained for Moon; Johns’ production was far more no-nonsense than the band’s previous work, only permitting gratuitous flamboyancy on rare occasions.) Townshend’s songs unbox his thoughts in a way that is always powerful and often very intimate, and Daltrey’s delivery is unfailingly strong. For all the raging energy and sheer anger that runs through the album, Behind Blue Eyes, for example, is not done justice by the word ‘beautiful’; it is tragically heartbreaking and scornful, as well as brilliantly written.

Whilst The Who had always been excellent, this was new ground for them on many levels. They made far greater use of synthesisers than possibly anything that had come before; they weren’t just window dressing, they were absolutely integral to many of the tracks. In the opening track, Baba O’Riley (named for the aforementioned Meher Baba and musical influence and minimalist composer Terry Riley), the stage is set by inputting information about Townshend’s life into a synthesiser, from which the music was generated – before the absolutely unforgettable power chords that announce the band’s appearance.

Johns also fostered a different approach to music-making within the group. Live, the band were frantic, out of control; Christgau, in his review, describes Townshend’s habit of “smashing shit out of his guitar at the end of performances.” Previous manager Kit Lambert, who had become estranged from the band during the Lifehouse saga, had nurtured that image, but hadn’t bothered to try to tame it for studio purposes. Johns recognises that recorded albums require something different, and on Next manages not to tame the energy of the group, but rather to focus it; it is precise and calculated, but nonetheless genuine for that. The energy still comes through.

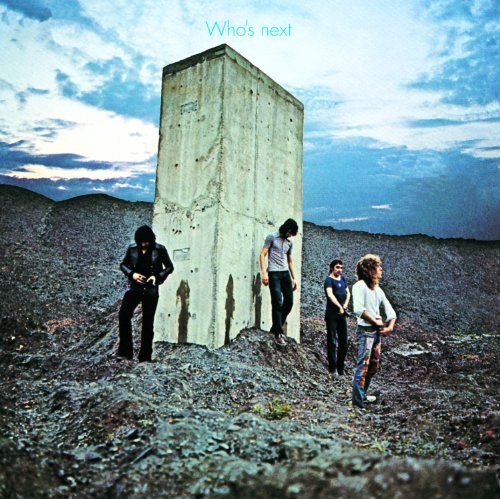

Also worth noting is the album’s artwork, named by TV channel VH1 one of the greatest album covers of all time in 2003. The group is depicted having just urinated on a large concrete slab rising up from a slag heap (possibly poking fun at the monoliths from 2001: A Space Odyssey, but perhaps simply a comment on the band’s previous grandiose pretentions). An alternative cover depicted Keith Moon dressed in black lingerie with a brown wig and holding a whip. This was rejected – as Chris Roberts, writing for BBC Music, notes, we should “be grateful for small mercies” – but was used as the inside art for CD releases in 1995 and 2003.

Overall, the album is an absolute tour-de-force for hard rock; it sets a standard that its creators themselves found it hard to live up to. Baba O’Riley, Behind Blue Eyes, and Won’t Get Fooled Again are masterpieces, and manage to stand up even among this distinguished crowd of songs. They all make the playlist I am creating with this series, along with Love Ain’t For Keeping and The Song Is Over; you can listen to them here.