Baiga mother and child (Image courtesy of Survival International)

1980s: Half the members of the remote Nahua tribe die from flu epidemics, after Shell’s exploration for oil in the Peruvian Amazon.

2014: Russian oil giant LUKOIL attempts to take over the land of reindeer-herding Komi-Izhemtsi people in Siberia for oil exploration and drilling.

2015: Indigenous Baka “Pygmies” in Cameroon are evicted and abused in the name of… conservation?

We know about the threat posed by oil, gas and logging and mining industries to tribal peoples’ land and lives. But conservation? According to recent reports and increasingly desperate calls by indigenous people worldwide, “conservation” is their new and biggest enemy and its activities “now represent the single biggest threat to the integrity of indigenous lands“. It’s well established that tribal peoples are the best conservationists, as we see from their land being rich in biodiversity. So what exactly is happening and why?

A quick look at the history of western conservation reveals this isn’t a modern conflict. Enshrined in the first big conservation projects is the idea of ‘wilderness’, a virgin land unpopulated by humans, as being the only way to protect animals. The creation of Yellowstone National Park, The Serengeti National Park and Yosemite National Park entailed the eviction of the tribes who had lived there for thousands of years. Since then, millions of people worldwide have been expelled from their land, in order to protect the animals they have lived alongside harmoniously for generations.

The boom in financial support for international conservation in recent years – USAID pumped almost

This Baka man told Survival International that he was beaten twice by anti-poaching squads in Ndongo(Image courtesy of Survival International)

Most evictions are illegal and forced, or take place under coercion. Although national and international law says they are allowed to stay, tribes in India’s Kanha Tiger Reserve (setting for the Jungle Book) were routinely arrested, fined, beaten and bullied by forest guards until they left. Often promised money and land they never receive, tribes in India are left landless and penniless on the margins of society. Once self-sufficient and proud, they are stripped of their sense of identity and their land; mental and physical illness, malnutrition and alcoholism soar and life expectancy plummets. Similar cases are being reported all over the world, from Botswana to Thailand.

Aka ‘Pygmy’ mother and child play in the Congo Basin(Image Courtesy of Survival International)

A recent report by Survival International, the global movement for tribal peoples’ rights, shines light on cases of abuse of tribal peoples in the name of conservation. Most arresting is the plight of the Baka “Pygmies” in Cameroon, who are forced to spend much of the year living by the roadside, where many say their health has plummetted. They are abused, beaten and arbitrarily arrested by anti-poaching squads when they venture in their lands to hunt for food. Astonishingly, these anti-poaching squads, who terrorize the Baka whilst turning a blind eye to organized poaching gangs, are funded by the WWF and the German government.

Human rights aside, does this model of conservation work? Despite the doubling of the total area of land under conservation protection since 1990 (over 12% of land or 11.75 millions square miles), reports show that species are disappearing faster than ever.

Evicting tribal people makes no sense; they are the original and the best conservationists, and evidence demonstrates that they are vital in the maintenance of a park’s eco-systems and biodiversity.

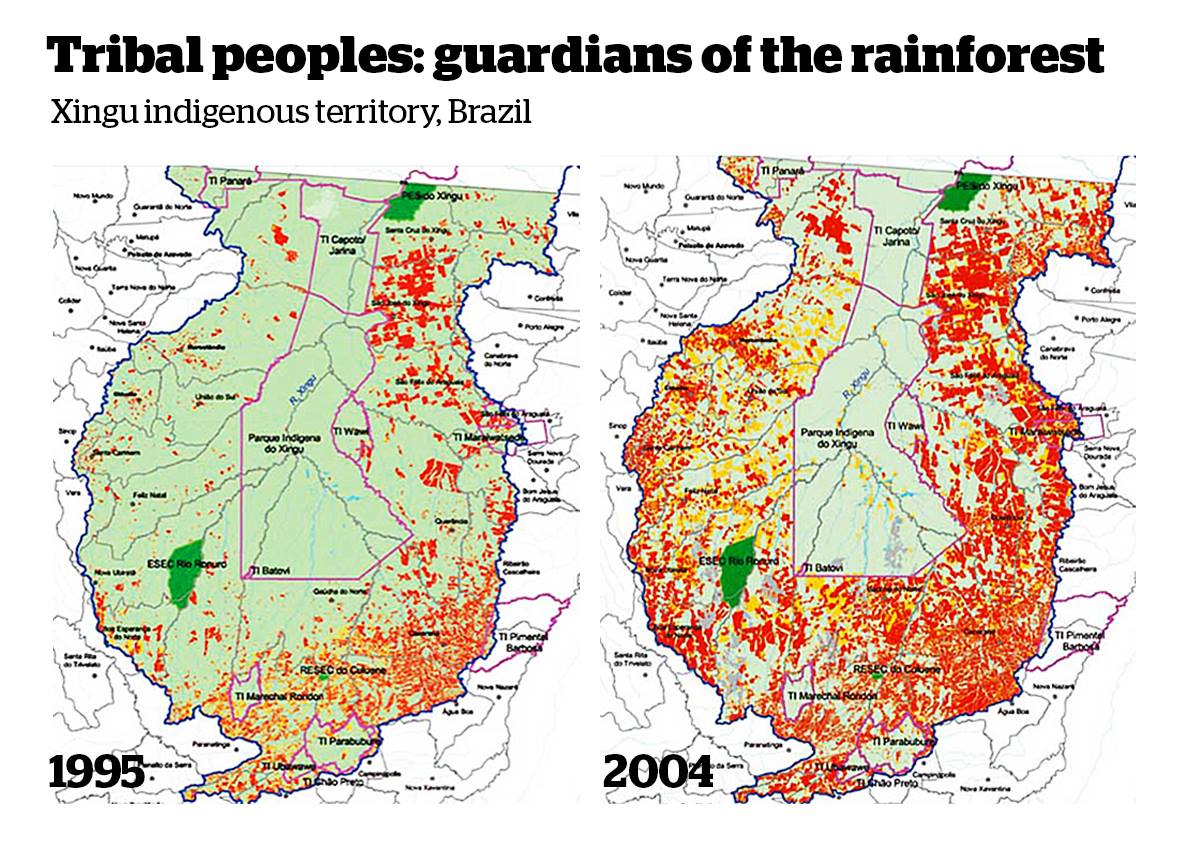

Xingu indigenous territory acts to halter deforestation in Brazil(Image courtesy of Survival International)

Tribal peoples’ intimate knowledge, respect and dependence on the land and its occupants means they are far more motivated and better equipped to protect it than anyone else; especially than poorly paid and corruptible park rangers, far from their families and with little local knowledge. At the heart of indigenous land management is the maintenance of natural resources – “over centuries, tribal peoples have developed complex social systems to govern the harvesting of the wide range of species on which they depend to ensure a sustainable, plentiful yield” (Parks Need People report).

For example, many tribes have developed shifting cultivation systems, a type of rotational farming in which land is cleared for cultivation (normally by fire) and then left to regenerate after a few years. Scientists are increasingly realizing that this system can “harbor astounding levels of biodiversity”, by creating important habitats.

The Dongria Kondh have lived in the Niyamgiri Hills of Odisha, India, for thousands of years. A recent study found that they collect almost 200 different foods from their forests and harvest over 100 crops from their fields, engineering an extraordinary diversity of flora and fauna which keeps them self-sufficient all year round. Not only that – their campaign to protect their land prevented mining giant Vedanta Resources from ecologically devastating the entire area. How revealing that the Convention on Biological Diversity has documented that in Africa, with its thousands of new parks and reserves and high indigenous eviction rate, 90% of biodiversity lies outside of protected areas.

In India, villages inside tiger reserves create special grassland habitat for grazing animals that are important prey species for tigers. Research into wildfires in Australia has demonstrated that Aboriginal methods of controlled burning found that they were an effective method of keeping wildfires at bay and yielding higher produce from the land.

Tribes are also allies in the fight against deforestation; we must recognise their role as stewards of the lungs of the world. Usually, wherever their land rights are recognized, the land is protected from deforestation (although illegal loggers are still a problem) and their presence in a forest can reduce the risk of deforestation more than the existence of a PA. The map below shows how the Xingu indigenous territory, home to several tribes, provides a vital barrier to deforestation.

Central to tribal peoples’ messages to conservation is simply that hunting for sustenance is not the same as poaching. The Bushmen of Botswana are ruthlessly persecuted by a government desperate to evict them from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, despite their legal right to remain. Diamonds were discovered in the reserve in the 1980s and although President Ian Khama (who sits on the board of Conservation International) has always denied these eviction attempts are connected with diamonds, the subsequent violent evictions of the Bushmen, and the construction of a diamond mine in the following years, suggest otherwise.

Are we too blinkered by our own ‘extractivist’ and exploitative relationship with nature to conceive that others may have found a better way? Tribal peoples have a larger stake than any of us in the preservation of the world’s forests and savannahs and the beautiful animals they contain. They show us that sustainable, harmonious and mutually beneficent cohabitation between humans and wildlife is possible. Yet, the very people western conservationists should be learning from are those suffering the most under this broken model. Conservation needs reforming. It must stick to international law, stop breaching human rights and put tribal people at the centre of the process. Let’s learn from existing models of community and indigenous centered conservation programs, to ensure that conservation helps more than it hurts.

“If we want to preserve biodiversity in the far reaches of the globe, places that are in many cases still occupied by indigenous people living in ways that are ecologically sustainable, history is showing us that the dumbest thing we can do it kick them out.” Mark Dowie.

“Our relationship to the forest is like a child to its mother. The western environmental groups can’t understand that.” Muthamma, a Jenu Kuruba leader form Nagarhole Tiger Reserve.