Is an ancient script too far removed from modern law?

I was lucky enough last week to attend a debate hosted by The Hampton Trust and organised by The Freedom Association at Durham Cathedral as part of Durham’s celebration of 800 years of the Magna Carta. The speakers were both eloquent, and whilst debating respectively from history and law backgrounds, what they said had much to do with the philosophy of free speech. I’d like to focus during the course of this article, however, on an issue brought to the attention of the audience by the speaker Professor Helen Fenwick.

The issue in question is the ongoing investigation into a student diversity officer at Goldsmiths University accused of hate speech. The 27 year-old is accused of posting on Twitter ‘Kill All White Men’ and on Facebook uninviting males and white individuals from an event promoting diversity and equality. Despite the obvious contradiction here, it remains to be discussed whether the freedom of speech Britons assume to be their human right extends to offensive language, and how far this can be monitored on social media. In fact, in the UK today freedom of speech isn’t treated as an absolute right, and hence instances like this can indeed be brought to court. In an age when social media dominates lives it is important to establish clear guidelines on what can and cannot be posted online. Whilst most would agree oppression and restriction of free speech are wrong, intent to offend is surely equally wrong and the two need to be delicately balanced.

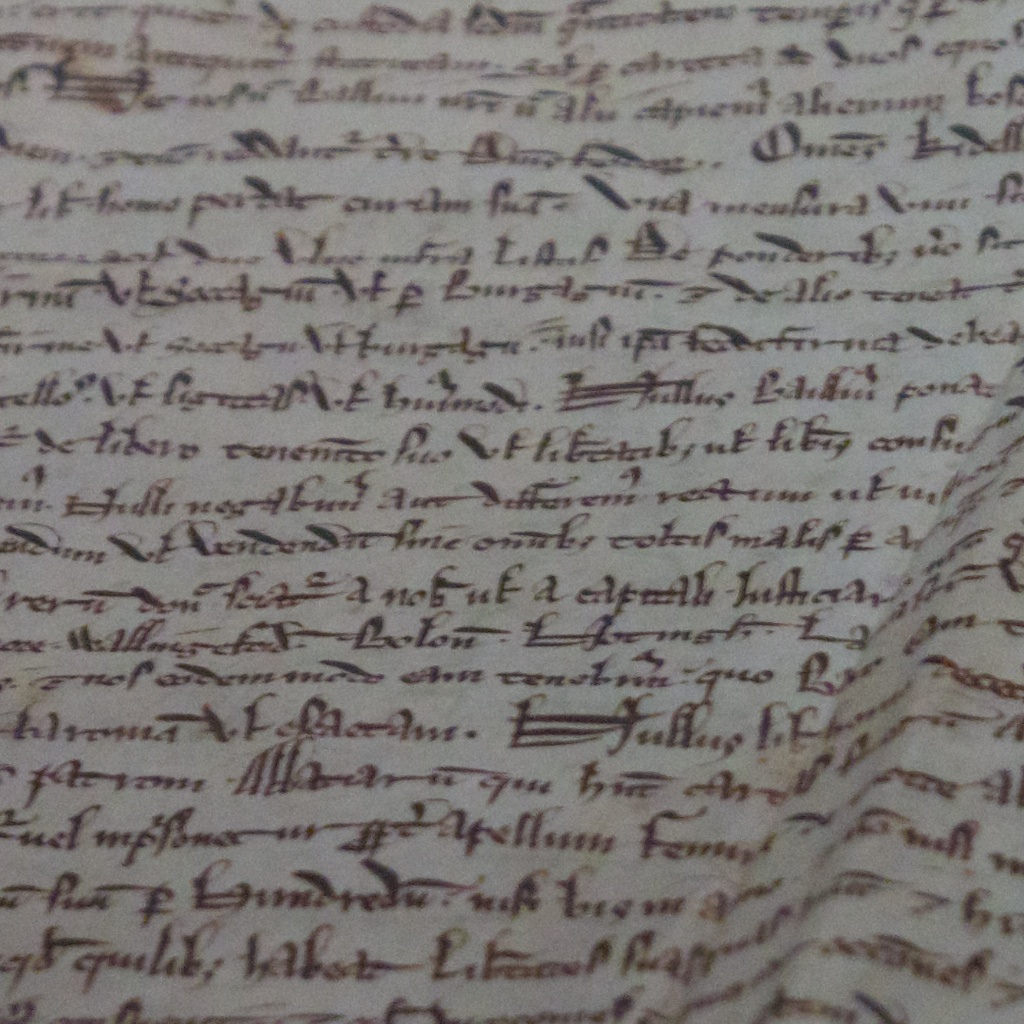

Perhaps in the UK today it would be useful to look back in time to the laws on free speech which have previously underwritten all human activity, and thus surely also apply to our online presence today. Given the current public awareness of the Magna Carta it may be suitable to look to this document for advice. After all, the writers of the Magna Carta have been described by some as freedom fighters, a similar description as the individual in the case above would give of herself as a woman from a racial minority fighting for equality. Whilst the Magna Carta did nothing for the cause of women, and in fact could even be read as a misogynistic document, there is no reason why its clauses, if they had power in the past, can’t be reimagined in our more tolerant society today.

The second speaker at last week’s event, Professor Michael Prestwich would argue not, and I would be tempted to agree. Even in its own time, the reach of the Magna Carta’s very general clauses shouldn’t be exaggerated, their generality also essentially ruling them out of use in modern law. Professor Prestwich also runs counter to much historical thought by arguing that the barons who wrote the Magna Carta were actually not freedom fighters, but solely interested in specific freedoms for their own division of the English nobility. As such, the use of the Magna Carta itself is unlikely to be useful in the formulation of modern day laws on free speech, especially in a society so removed from 1215 that one can be imprisoned for something one posts online. The myth surrounding the Magna Carta idolises it as a beacon of liberty, democracy and free speech. But once you scratch the surface, the document’s applicability to life today is highly questionable, especially as its applicability to life in the 13th Century is equally questionable.

Moving forward, then, and in the construction of new laws limiting freedom of speech online, an alternative philosophy to the Christian theology underlying the Magna Carta needs to be sought. It’s even up for debate just to what extend free speech is desired and should be permitted.