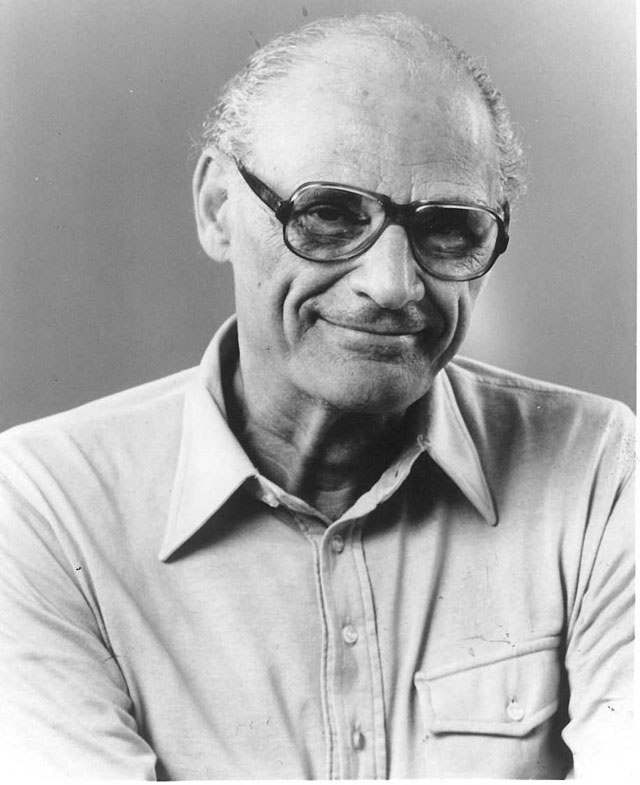

A photograph of Arthur Miller, American playwright.

This year we celebrate the one hundredth anniversary of American playwright Arthur Miller. He is often remembered for his essays, interviews, and his five-year marriage to Marilyn Monroe. His fame, however, comes mostly from his plays, of which he wrote an impressive number, and which have been frequently staged all over the world from their first release to the present day.

Death of a Salesman is one of Miller’s most famous works. First published in 1949, the play is set on the outskirts of New York in a peaceful, middle-class suburb in the decades following the “Great Depression” of the 1930s. Willy, an ageing salesman on the brink of nervous breakdown, lives with his patient, loving wife, Linda, and his two sons, Happy and Biff, who have come home to resolve some of their existential (and financial) troubles. Throughout the play, Miller takes us back and forth between past and present, between a time of hope and security and one of fears and tensions. It’s a story that takes us through a straining whirlwind of hopes and disillusions, fights and reconciliations, from the American ideal of a happy, prosperous family to the final reality and downfall, foreshadowed throughout and implied by its very title. It is a play about familial breakdown and the “death of a salesman” in “Two Acts and a Requiem.”

My first encounter with this play was a shock. Many years later all I remember is an endless stream of shouts, cries and explosions. It was about four years ago and our teacher had taken us to watch a production in Broadway, New York. I had read a few reviews beforehand, all praising the talent of the actors and the audacity of the staging. When the time to see the play arrived, however, I was taken aback: I was too disturbed by the power of the sound effects to focus on the plot; everything seemed to be moving along with a hurried bitterness. I grew increasingly uncomfortable as the family fights became more violent and, after jumping at the sound of every car-crash, I was left feeling confused, miserable and slightly shell-shocked by the play’s conclusion. Needless to say, after this traumatic event I had no great desire to familiarise myself any further with the works of Arthur Miller. But as it turned out, I was to become acquainted with the great American playwright many more times.

For many of us, studying Arthur Miller in school has been a troubling experience. Whether reading the plays or watching them staged, it is hard to remain indifferent to the brutal showcase of human folly and the disturbing observations they make on our society, both past and present. Perhaps this can explain the conflicting feelings I have experienced in regard to Miller’s plays – a mixture of fear, interest and, perhaps morbidly, attraction. At first sight, Arthur Miller appeared to me a mean writer. It baffled me that an author could not only make the lives of his characters a living hell, but also insist on their mediocrity, dragging them page after page, act after act, into deeper levels of humiliation, baseness and ridicule.

However, as I plunged deeper into my analysis of Death of a Salesman, I began to see a more nuanced critic. Though the main characters all have certain weaknesses, still they are complex, layered, and much more human than I had first perceived. They have flaws of their own but they are also victims of their time. They may be responsible for questionable actions, but they are deep down convinced that they are doing the right thing. Indeed, if Death of a Salesman is such a shocking play, it may be because it strives to reflect equally shocking realities. Miller pushes us to recognise the most violent aspects of American society through its simple yet alarming depiction; whether of toxic masculinity, the failures of the economic system, or the growing price of education. Death of a Salesman is not simply the story of a family, nor simply that of a society; it mingles personal and historical movements and struggles into one to show us the deep effects of national themes (the fallacy of the clichéd “American Dream”) as well as more personal ones (parental pressures). Miller once wrote: “I could not imagine a theater [sic] worth my time that did not want to change the world”. Indeed, if Miller’s plays are worth our while it is first and foremost because they beautifully and effectively challenge our views of the world, striving to change the latter altogether.

Yet this is not the only reason why Miller’s plays remain unequivocally important. Arthur Miller is not an artist whose art is purely political, nor an artist who destroys without ever truly creating anything. If his characters lack heroism, if they are at an all-time low (note the salesman’s name, “Loman”), then it is all the more daring and original for Miller to give them such centrality in his plays. In “Tragedy and the Common Man”, Miller explains how he aims to innovate by applying the traditional pattern of classic tragedies to “common people”, and this is perhaps his most appreciated addition to drama. However, Miller innovated in many other domains: through his creative use of staging, his use of light and movement to show shifts between past and present, and through his use of sound effects. These sound effects were what baffled me most, but I’ve come to see them as brilliant innovations: Miller beautifully utilises music to reflect human feelings, whilst also using sound effects to create violent reactions from an audience. Indeed, what better way is there to incite pain than through “[a] single trumpet note (that) jars the ears”? And are not violent explosions the perfect means of creating a sense of urgency and catastrophe? In short, I think Miller is remembered for having made the most out of his beloved literary form – drama – and, in a way, for bringing it into the age of the movie.

It has often been observed that whereas most countries’ literary canons are quite clear – in Britain we immediately think of Shakespeare, Dickens, Byron – the United States’ canon is much less so, perhaps because of its shorter history, or the difficulty of defining what is “American”. But as time goes on, and as writers leave their mark, an American canon is forming, one in which writers who have discussed American experiences, questioned American culture, and redefined entire genres should most definitely belong. I thus have reason to believe that Arthur Miller will long endure in the great American literary tradition. As we celebrate his one hundredth birthday I hope that he will be celebrated as he rightfully deserves; that as many people as possible will be exposed to his wonderful works and be made, as I have been, to reconsider the art, the tragedy and the beauty in human lives.