Upon securing victory in a splintering and deeply factional election, Emmanuel Macron spoke of a new vision for a pluralistic French society, pledging in turn to “combat all forms of inequality and discrimination”. With this commitment came great expectation; Marine Le Pen, then his closest presidential rival, had reinvigorated a rural working-class base previously detached from national political proceedings. Much like the US had experienced with Donald Trump, these voters were primarily mobilised by nationalist-populist rhetoric—designed not to unite but to divide. In truth, the shadow of Europe’s migrant crisis had installed a new political dynamism across the continent: Germany, Spain, the UK and Italy all experienced nationalist movements tied closely to the discourses of identity, religion and ethnicity. Yet, Macron stood tall. Having simultaneously encharmed France’s centre-left and right, he claimed the keys to The Elysée Palace by cobbling together a package of economic reconciliation and modern liberalism.

That was in 2017. Now, confronted with the complex challenges of uniting a country reeling from the pandemic, Macron is struggling to define his legacy ahead of next April’s presidential election. Unlike his spirited calls for unity and hope—now firmly entrenched in the past—the French president presides over a people characterised by socioeconomic division. While it is true that he sits comfortably ahead in the pre-election polls, France has not changed as he would have hoped: the 2019 gilet juanes movement—the longest-running protest in the country’s history—is a useful reminder of just how splintered French society is.

Image one- Emmanuel Macron: A hidden populist? (refer to image license at the end of the article)

In many respects, though, the nature of Macron’s political fortunes has always been linked to social and political polarisation. His image was presented as one of modernity and newness, offering a different way of ‘doing politics’—a counterpunch to inefficient, inertia-ridden policy making. Yet, somewhat ironically, the successes—and failures—of Macron’s presidency can be linked to a broader Trumpian reality. He was the populist anti-politician, calling for a ‘revolution’ against political elites: “The real cleavage today is between backward-looking conservatives…and reformist progressives”. Indeed, his attack on regressive conservatism— aimed at both the establishment left and right—was a conduit through which he successfully mounted his presidential ambitions.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the upcoming presidential election is one built firmly on populist foundations. The Macron presidency has itself been a precursor to this: the paradoxical ideals of being simultaneously pro-market and radically environmental; of being inclusive yet decidedly hard-line on Islam; and of espousing an ‘us’ and ‘them’ rhetoric, all point to the inevitable polarisation of next year’s electoral discourse. The tacit irony of the Macron phenomenon, though, is that populism—no matter how innocent the intention—is a perilously hard means through which to fight other strands of populism. In essence, it justifies the existence of repugnant brands of politics. The newly-found international infamy of Éric Zemmour emphasises this actuality.

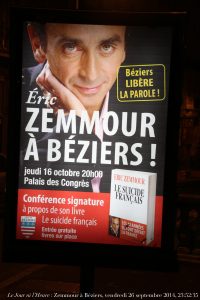

Zemmour, a well-known media personality in France, is recognised for his provocative and divisive ideals—one such description even anointed him as the country’s “TV-friendly fascist”. His rhetoric mimics this ideation: his best-selling book, The French Suicide, considers political progressivism, sexual freedom and modern morality to have corroded French society. Immigration, too, amounts to warfare; in his eyes, cross-continental immigration should be countered by ‘walls being built wherever possible’. These ideas—however ridiculous or unpalatable—are gradually becoming mainstream, with Zemmour now of sufficient legitimacy to mount a serious presidential run.

Image two- Éric Zemmour: polemicist turned presidential candidate (Refer to image rights at the end of the article).

He engenders, then, a long-term shift in what is considered to be ‘normal’ in political discourse. Indeed, Marine Le Pen, having lost the presidential election in 2017, ran a campaign of thematic similarity, though her defeat prompted a moderation of her message. Yet, Zemmour’s aggressive strategy has railed against the perceived weakening of her values. In launching his own campaign, he is not just merely reacting to the limitations of Le Pen herself—he is revolting against the sanitation of her philosophy. In other words, the normalisation of her politics is seen as an opportunity to push the boundaries even further: to work, nationalist populism needs to be reactionary and polemical, not fastidious or pragmatic. This tension is one that Zemmour has assiduously recognised.

The wider implications for France are clear. Antagonism will likely be ramped up during the 2022 election, increasing as the race quickens. The discourses of moderation, like those employed by Valérie Pécresse, will be corrupted by the forces of populism: there is appetite for sensationalism and abstract idealism— the chances of clinching the presidency will rely on candidates’ ability to dance to this beat.

Main featured image: Jacques Paquier via Flickr with license.

Featured in-text image (1): Jeanne Menjoulet via Flickr with license.

Featured in-text image (2): Renaud Camus via Flickr with license.