The UK government’s claim that 44.4% of household waste was recycled in 2020 is severely misleading; the majority of household waste is incinerated or dumped in landfill sites. If you haven’t already, check out part one of this article which explains this in more detail.

Zero Waste Products – Unsplash: Anna Oliinyk

While paper, cardboard and glass can pose environmental issues, plastic is a far more problematic material to recycle. The process of sorting plastic waste and high energy and capital costs all make it not economically viable and have severely hindered its implementation. In fact, one estimate suggests that only 9% of all plastic ever produced has been recycled. While it may be tempting to see this as solvable, it is important to remember that recycling decreases plastic quality. Recycled plastic must be combined with virgin material and can only be recycled 2-3 times. Even if recycling could be made economically viable, plastic waste would continue to be a critical problem.

If this is the case, why is recycling so prevalent? In the 1940s and 1950s, plastic companies emerged (largely from within the pre-existing oil industry) as mass production began. Internal documents from the 1970s show that top executives in the industry knew that ‘recycling plastic on a large scale was unlikely to ever be economically viable’. However, in the 1980s, the industry began spending tens of millions of pounds promoting recycling. During the 1980s and 90s, political initiatives to ban or curb the use of plastic gained traction and numerous former plastic industry officials have confirmed that recycling was promoted as a counter-measure to this. Put simply, the plastic industry knew that recycling was not a viable option but promoted it for the sake of their own profit, shifting responsibility for the waste to consumers.

“There was never an enthusiastic belief that recycling was ultimately going to work in a significant way.” – Lewis Freeman, Former Vice-President of the Society of the Plastics Industry

Resin Identification Codes – Wikimedia Commons: Filtre

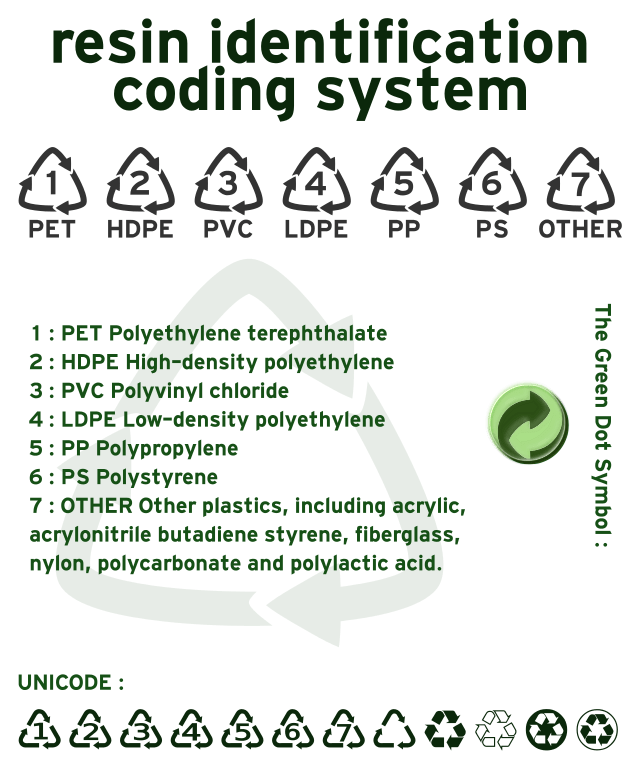

One of the most notable groups within the plastic industry is the Society of the Plastics Industry (known as Plastics Industry Association, PLASTICS since it’s re-brand in 2016) which invented the resin identification code in 1988. Resin identification codes are placed on plastic products to identify which plastic resin it is made of, facilitating recycling by simplifying the sorting process. On paper, this sounds like a wonderful idea but there is a key problem: the code is suspiciously similar to the recycling symbol which became open domain 18 years prior. Discussion of the motivation behind this would be purely speculative but it is easy to say that consumers have been confused into placing non-recyclable plastics into recycling bins by the resin identification code. In 2013, the standard for the symbol was changed from arrows to a triangle to address mass consumer confusion amongst other things.

“If the Public thinks that recycling is working, then they’re not going to be as concerned about the environment.” – Larry Thomas, Former President of the Society of the Plastics Industry

The plastic industry has fooled the public into believing that recycling will offset it’s negative environmental impact. This will never be the case. Even if recycling could be made economically viable, plastic waste would continue to be an international problem. These conclusions aren’t new, the plastic industry has known about them since the 1970s, and recycling schemes are largely a distraction from the environmental damage done by plastic. Fortunately, there is hope. The United Nations is in the process of developing a global treaty on plastic pollution which should impose limitations on the plastic industry and decrease virgin plastic production.

Litter Picking – Unsplash: OCG Saving The Ocean

If you feel passionate about the issues that have been discussed here or in part one, there are various ways you can help address the global waste crisis aside from reducing your own waste. On the Durham University Student Volunteering and Outreach (DUSVO) volunteering platform, you can join litter picks which will prevent waste from harming local wildlife or beginning it’s journey to the oceans or rivers. The Climate Society has created a College Sustainability Policy which advocates for avoiding ‘purchasing single-use plastic and non-biodegradable products’ but Hild Bede is so far the only college to adopt a sustainability policy. In order to reduce the university’s waste production, you could help the society promote the policy to other colleges. Most importantly, you can write to your MP and ask them what actions they are taking in response to the global waste crisis.