Christmas is approaching, a perfect time to see a ballet with your friends or family. But did you know that many famous ballets were adapted from fairy stories? In this article, I will explore some of these fairy tale origins and discuss how their stories have been changed in their later ballet adaptations.

First, we have The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, a fairy tale by the renowned German writer E. T. A. Hoffmann. The story centres on Marie, who is given a nutcracker doll by her enigmatic godfather Drosselmeyer. The nutcracker comes to life at midnight, and with Marie’s help manages to defeat an army of giant mice and their king. Later, Drosselmeyer tells the origin story of the nutcracker to Marie, revealing than an evil Mouse Queen initially transformed a princess into a nutcracker. Drosselmeyer’s nephew reverses the spell but he is then enchanted into a nutcracker himself, causing the princess to break off her engagement with him. That night, Marie helps the nutcracker to defeat the Mouse King for the final time, and vows that unlike the princess, she would love the nutcracker regardless of what he looked like. This lifts his curse, and he is transformed back into Drosselmeyer’s nephew. A year later, he and Marie are married. The ballet adaptation of this tale, The Nutcracker, broadly follows the first part of Hoffmann’s story, but then diverges. The nutcracker turns into a prince after the first battle with the Mouse King, then whisks away the heroine (called Clara in the ballet) to the magical Land of Sweets. There, she witnesses displays of delicacies from around the world and a special performance from the Prince and the Sugar Plum Fairy. Although the ballet has a lack of plot by omitting the nutcracker’s backstory, this might be why it’s so popular. Rather than having to concentrate on the story, the audience can enjoy the beautiful dancing instead.

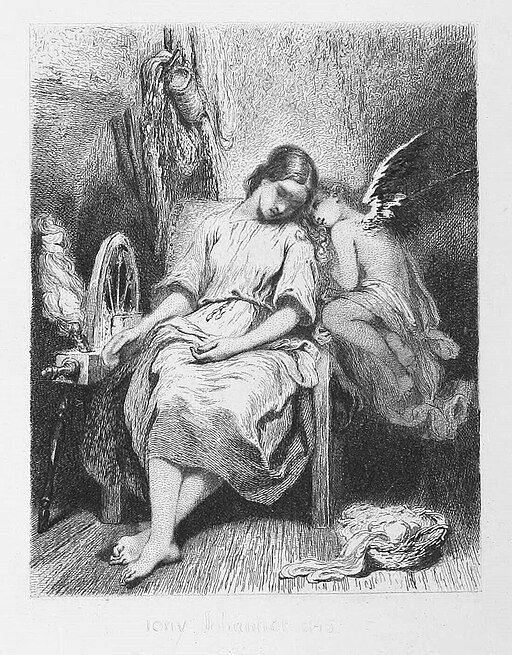

Next is the fairy tale Trilby; or, The Fairy of Argyll, written by French author Charles Nodier but set in Scotland. A fisherman’s wife, Jeanie, is admired by a male sylph (a type of air spirit) called Trilby who takes care of her cottage and lives in its hearth. When Jeanie’s husband Dougal finds out about Trilby, he gets a monk to exorcise him. Trilby disappears, but Jeanie keeps hearing his voice in a casket found by Dougal, begging her to confess her love to him so he will be released from captivity. Jeanie refuses because she isn’t willing to break her wedding vows, so Trilby dies. Heartbroken, Jeanie commits suicide by jumping into an open grave. The ballet La Sylphide is adapted from this tale, and while it is also set in Scotland and depicts a human falling in love with a spirit, the genders of the characters are reversed. The ballet depicts a young man named James who abandons his future bride Effie after he falls in love with an elusive female sylph. James is then tricked by a witch, who claims that if he throws her magical scarf around the sylph, she will lose her ability to fly and be bound to him forever. Instead, the scarf kills the sylph, while Effie marries James’s friend Gurn. Both ballet and fairy tale present their male human characters in a negative light, while their female protagonists meet an untimely death. However, the plots which result in the demises of the sylphs are broadly different.

Finally, we have another fairy tale by Hoffmann called ‘The Sandman.’ The story follows Nathaniel, who is given a telescope by a mysterious man called Coppola. He looks through the telescope at a girl called Olympia and falls madly in love with her, abandoning his fiancée Clara. Nathaniel goes mad when he discovers that Olympia is only a doll, but soon recovers and reconciles with Clara. However, he then accidentally looks at Clara through the telescope when they are standing on a tower. He goes mad again and attempts to push Clara off the tower, but she is saved by her brother. Nathaniel sees Coppola at the bottom of the tower and realises that he is the same person as Dr Coppelius, a mysterious man from his childhood who was thought to be responsible for his father’s death. This realisation causes Nathaniel to jump off the tower to his own death. Coppélia is the ballet adaptation of this tale, and follows Frantz and Swanhilda, whose love is put into jeopardy when Frantz becomes infatuated with Coppélia, a beautiful girl he sees in the house of a dollmaker called Dr Coppelius. Swanhilda breaks into his home to discover that Coppélia is a simply a doll, then hides and watches as Dr Coppelius drugs Frantz so he can sacrifice him in order to bring Coppélia to life. Swanhilda saves Frantz by pretending to be Coppélia coming to life, causing Dr Coppélius to faint and allowing the couple to escape and get married. The happy ending of the ballet is far from the tragedy of the fairy tale, and focuses solely on its male protagonist’s love for a doll, rather than his madness and tragic backstory. The fiancée is also given a larger role in the ballet, making her a more interesting character.

All three of these ballets are adapted from fairy tales with darker undertones. The fairy tales explore in detail the backgrounds behind their magical and supernatural characters, which are simply taken at face value in the ballets. However, by reducing the more disturbing parts of their source material, the ballet adaptations create more enjoyable performances which draw attention to their amazing dancers.