The Durham University Choral Society (DUCS) Michaelmas Term Concert was a spectacular performance that exuded the energy that had clearly gone into its rehearsals. The line up of two full and vastly different pieces was an excellent choice, offering attendees the chance to sample all the stringencies of Haydn’s strong classicism and Britten’s playful tone.

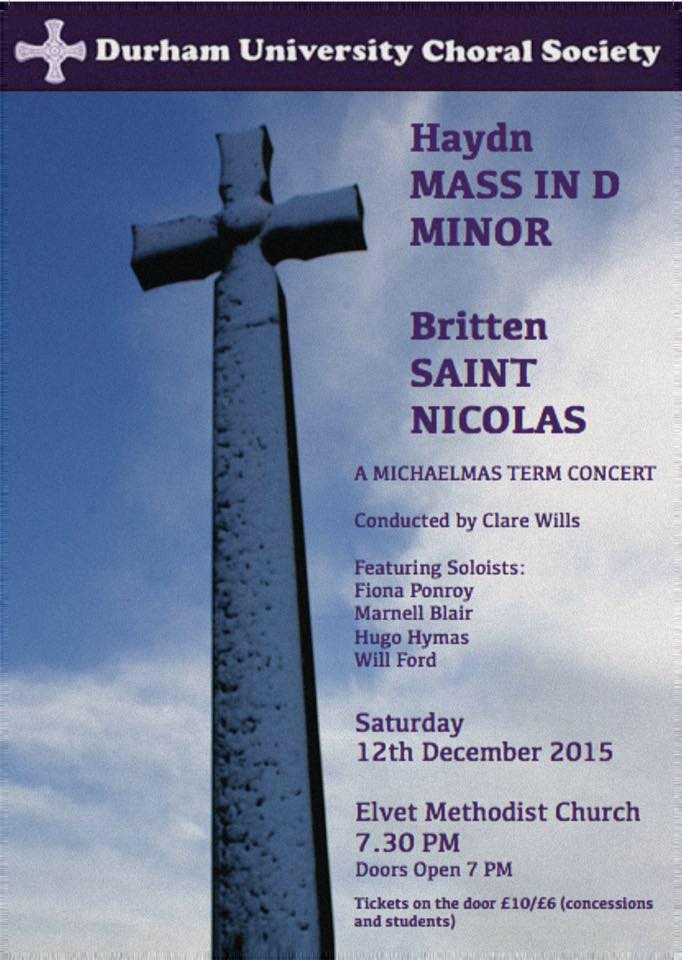

Durham Choral Society Christmas poster

The scene was set at Elvet Methodist Church, with the basses, tenors and altos standing in the chancel, while the sopranos formed a three-person line that almost reached the end of the eastern transept. In front of the singers was the orchestra, save the timpani percussionists which were located adjacent to the sopranos. In the final row stood the conductor, the newly appointed Clare Lawrence-Willis, and the four soloists. The arrangement seemed of little importance, mainly for space considering the sheer number of sopranos, but as the evening progressed, it was easy to see (well, hear) that the sopranos were overpowering the other three voices of the choir, due to simple acoustics and distance. That, perhaps, was the only issue with the night.

To talk of the pieces, we need to learn a bit more about their history and style. Haydn’s Mass in D Minor is better known as Nelson Mass, though he never called it so (his official name for it was Missa in Angustiis meaning ‘Mass for Troubled Times’). At that time, he was the attached composer to the Esterházy family, a major land-holding family settled in Eisenstadt, Austria. Haydn lived with them, and wrote a mass every year for the Princess Esterházy’s birthday. This mass was performed for her in 1798, and perhaps that very day, word came that Europe’s turmoil had been put to an end by Admiral Nelson’s stunning victory over Napoleon in the Battle of the Nile. Indeed, 1798 had been a difficult time for Austria since they continued to lose against Napoleon and Vienna was threatened with invasion, inciting the original title for this piece. In 1800, Admiral Nelson was called back to England from his extended stay in Naples after the battle, and so passed by Eisenstadt to visit the Esterházy family. There, Hayden performed his mass to honor the visitor, and perhaps from there on, it was thusly called (however, it is clear the mass was not written for Nelson’s victory since it was finished before the battle had begun).

At the time of the composition, Haydn’s patron Nikolaus II, had dismissed all the woodwinds in his orchestra, leaving Haydn with more constrains to the mass, and as the piece was performed often post-mortem, editors added the woodwind pieces to the orchestration, but modern versions tended to rely on the original. It presented technical challenges, especially to the soprano Fiona Ponroy, alto Marnell Blair, tenor Hugo Hymas and bass Will Ford, but all sections were executed well, controlled by the conductor’s skills. For those who didn’t know much of the traditional style of a Latin mass, it was a good lesson both in history and structure.

As for Benjamin Britten’s cantata, Saint Nicholas, we found ourselves in more modern and light-hearted territory. Saint Nicholas could easily have been the inspiration for Santa Claus, being the patron saint of children, making this an appropriate selection for the season. This piece was originally composed for amateur singers, and yet maintains a professional feeling in its arrangement. The cantata is in English, and tells the story of Saint Nicholas, with famous hymns interwoven in the music which the congregation were encouraged to sing along to. There were other detectable patterns as well, such as the waltz tempo that caught my attention immediately, a tempo that increased into a sort of mad descent as the section progressed. This cantata was led by the tenor solely, telling us Nicholas’s believable and mythical feats before concluding with the saint accepting his approaching death.

All in all, it was a magnificent way to cap the snowy Saturday, and for the £6 student’s ticket for the 2-hour performance, well worth its length. We can expect great things for future concerts.