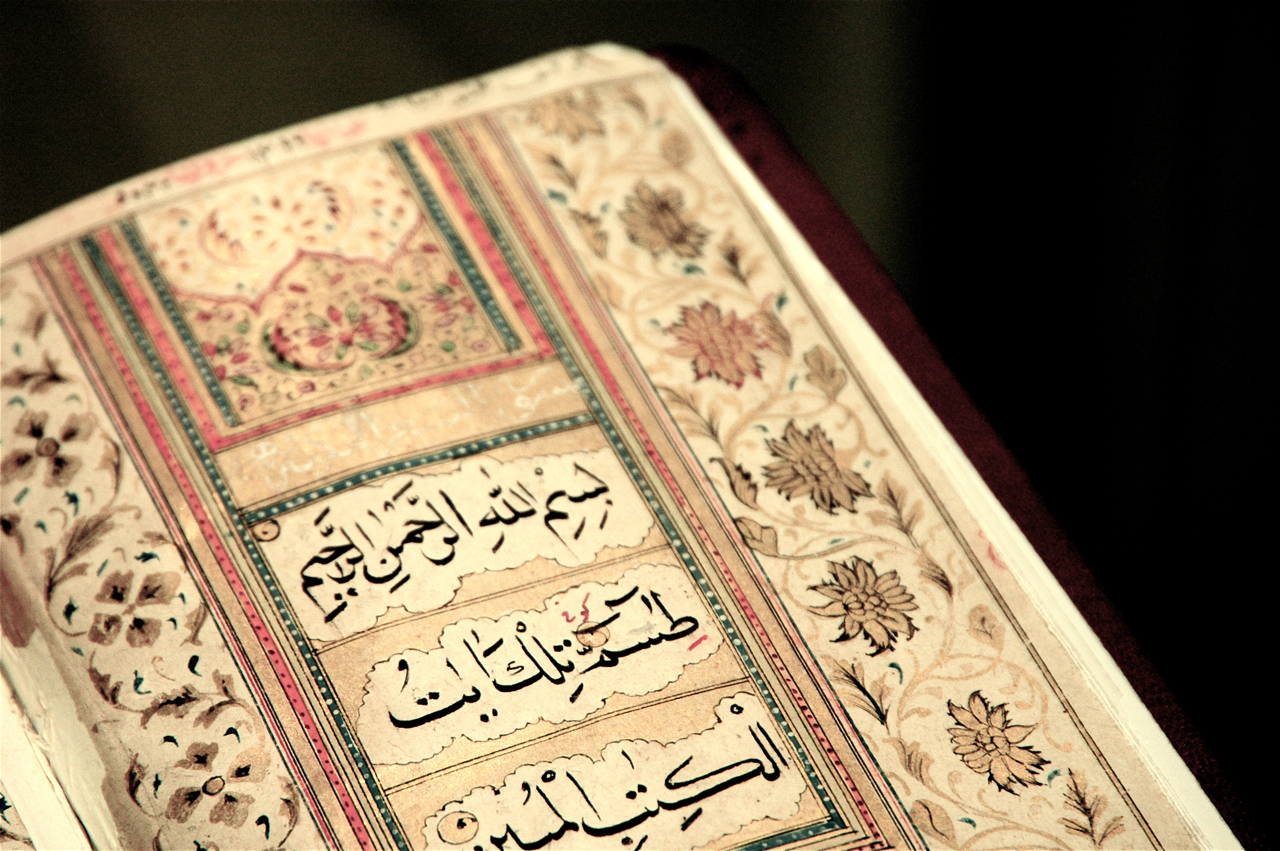

The calligraphic script of the Qur’an Attribution: Ahmed Bin-Baz under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

The sinuous lines and elegant arabesques of Arabic calligraphy have a special beauty even for those unfamiliar with the Arabic script. Arabic calligraphy is not only pleasing to look at, however; the importance of calligraphy for practitioners of Islam lies in its close associations with the Qur’an. Arabic, the language of Islamic calligraphy, was also the language in which the holy scriptures were revealed to the Prophet Muhammad in the 7th century. The status of the Arabic text of the Qur’an is therefore itself imbued with a sacred quality and thus works of calligraphic art, along with the calligraphers themselves, have historically been held in high esteem in the Muslim world. However, nowadays not all calligraphy is written in a religious context, which is part of what makes it such a diverse and fascinating form for contemporary Arabic artists -both religious and secular – to employ.

Ali Omar Ermes is a Libyan born artist who is internationally recognised for his Islamic calligraphic paintings. Ermes paints short excerpts and quotations taken from Arabic and Islamic poetry and religious scripture, or sometimes single letters of the Arabic script. The use of script allows Ermes to bring in written messages through which he can comment upon ‘human values such as justice, peace, human rights, protection of the environment and moral and social responsibilities’. Working in colour and on handmade paper, his works are rendered with a great sensitivity to space, colour, line and form. His works are instilled with a highly personal and meditative aura as he encourages his viewers, whether they are Arabic readers or not, to use his works as a route towards contemplation of social issues.

The theme of contemplation that Ermes brings into play is one that, historically, held a huge importance for the early inscribers of the Qu’ran. The experience of writing and illuminating the early Qu’ranic texts was one that required great diligence, dedication and discipline, making it into a ‘near-mystic experience.’ Furthermore, the embellishments added to Islamic calligraphic works create a similar need for careful meditation and contemplation within the reader of the text. The act of reading itself becomes difficult, requiring the reader to fully immerse himself in the text in order to come to understand its significance. It seems that Ermes himself attempts to recreate an immersive experience both for himself as creator and for his viewers. Like the early calligraphers, Ermes cures his own paper and carefully selects his colour palette in the same way that they would have meticulously blended their inks. It is this sensitivity and devotion that Ermes desires to recreate in his contemporary calligraphic works, to re-sensitise his audience to meaning.

Arabic calligraphy is not always at the service of religious contemplation, however. For many contemporary street artists operating in urban centres that were affected by the Arab Spring, calligraphy has melded with graffiti to create a hybrid form ‘calligraffiti’. This new style adorns walls and buildings throughout the Middle East and has fostered the artistic development of the Arab World’s answer to Banksy – the French-Tunisian artist ‘eL Seed.’ El Seed was profoundly influenced by the Tunisian uprising in 2011 and was subsequently inspired to paint graffiti artworks as a means of articulating his solidarity with protest movements.

eL Seed practising ‘calligraffiti’ Attribution: Thatcher Cook for PopTech under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

eL Seed, like Ermes, uses quotations from the Qu’ran, as well as from contemporary writers and poets; however, his aim is to express more politicised messages. eL Seed took on his first major public mural in 2012 as a means of celebrating the revolution in Tunisia and protesting against renewed censorship in the new regime. In the city of Kairouani, eL Seed painted a large-scale mural on a wall that had been used almost as a ‘public forum’ during the revolution, a place where citizens shared their thoughts and inscribed their protests. The wall became a written testimony to the strength and solidarity of the Tunisian people. However, shortly after Ben Ali fell from power, the wall was whitewashed, its messages effaced. eL Seed choose this wall in order to make a statement against censorship and as a means of commemorating the courage of the people that had chosen to speak out against injustice. eL Seed painted the wall with words from a Tunisian poem, the message of which spoke of ‘hope to all those engaged in struggles against tyranny, corruption, and injustice.’

The street art form allows eL Seed to reach all people through his art; in an interview, he said of the graffiti form: “I like graffiti because it brings art to everyone. I like the fact of democratizing art.” Indeed, the democratic nature of street art is a huge part of its appeal for eL Seed; as it is created and displayed in the public sphere, it allows other people to spontaneously participate in its creation and is fully visible to everyday citizens. Rather than lying hidden away in an art gallery, street art has a participative element and a symbiotic life with the city; it fuses with the cracks and puckers left by bullet holes, and with the passing life of the street. eL Seed, who has painted in cities all over the world, from Paris to Cape Town also insists that his works have resonance even for viewers that don’t understand the Arabic script. For him, the ‘shape of the script’ is as important as the words themselves, the ‘movement’ of the script is what creates a general feeling and a meaning. For eL Seed, line, colour, and shape can be as expressive as a poem; the shape in which the script moves across its surface as eloquent as a story. The ultimate aim for eL Seed is similar to that of Ermes, he desires to ‘lure the viewer into a different state of mind’, to access the contemplative centre that Ermes’s art also seeks to activate.

Calligraphy is, for these two artists, a powerfully expressive art form that allows them to speak both verbally, and through the malleable language of line, colour and form. The Arabic script, which can be interlaced in endlessly different, fluid fashions, is an artistic medium in itself, as infinitely varied as the colours that can be blended from the artist’s paint box. What unites these two artists is their focus on the transformation of the mind, and it seems that calligraphy, with its potential for extensive variation, is the perfect medium for such transformative energies to be expressed.