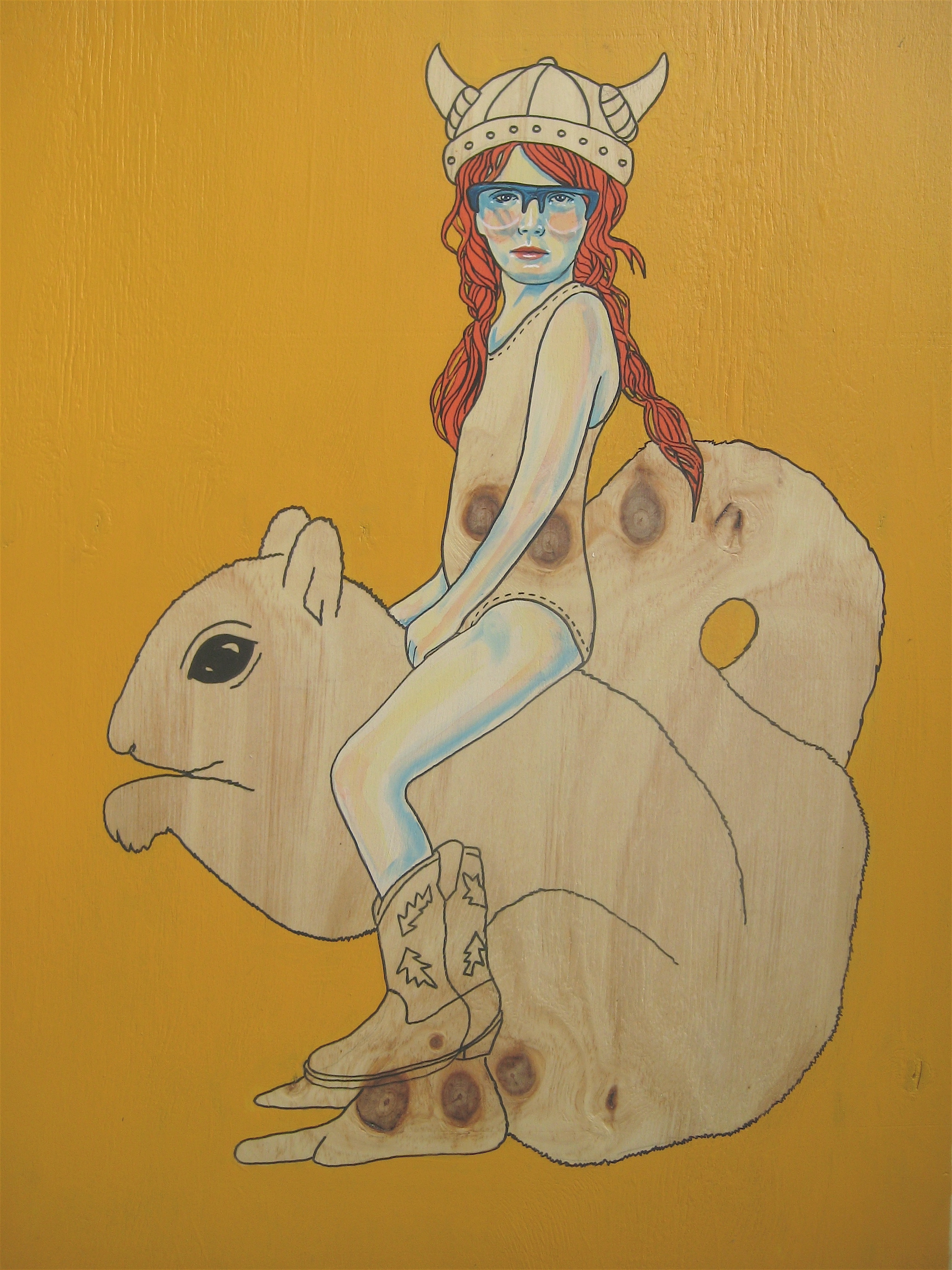

Ardilla and the Acorn Eater

Carmel Debreuil is a Canadian-Australian painter. Her portraits of children in fantastical settings can be seen as attempts to capture the “nonchalance and swagger of youth”, a realm where the imagination knows no bounds.

Enamoured with the nostalgic feel and originality of Carmel’s artwork, I jumped at the chance to interview her about the creative processes behind it…

Carmel, it’s safe to say that your artwork is unconventional in many respects. For example, you tend to paint straight onto wooden panels instead of, say, canvas. Why is this?

The wood is the beginning of the painting. I love using the knots and the grain as features of my pieces. Often the wood itself will dictate what I paint or at least where I place things. The knots often become animals’ eyes or details in a hat or a boot. I’ve also found a few pieces of wood that have these little flecks all through almost like leopard print, so they have been amazing to paint on. while I was in Canada too I got plywood that was made of birch, rather than pine like here in Australia, and it had these little hair like dark lines on this really pale wood and it kinda felt like it was snow or wind or something so it worked really well with the paintings inspired by the cold prairie winters.

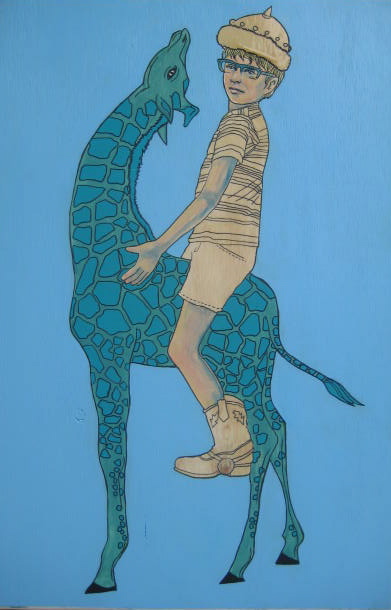

The Less She Spoke

Your trip to Canada also seems to have inspired the wintry colours in that particular series of recent paintings.

It did, which was surprising as I am usually drawn to bright colours. It was the middle of winter so everything was pretty much white and the only major colours were at sunset where you would get these soft pinks and blues and a bit of gold and then it would turn into these amazing rich shades of blue until the sky went fully black.

But Down Under it’s quite lush and green with seasonal flowers all year round, so it seems natural to paint in super bright colours.

What about the exuberant patterns on clothing and in the background, are they informed by different landscapes too?

Different landscapes, and foreign artisanship – lace, quilts, Indian henna tattoo patterns, native Canadian and Metis beadwork as well as the movement of clouds and the ocean. Stars invest a painting with a more theatrical feel, like a Baz Luhrmann film.

Stretch

That’s a pretty diverse array of influences! How do you even begin to weave all of these elements together into one coherent painting?

It all starts at the hardware store where I go and pick out my sheets of ply from the pile. Each one is handpicked for the features in the wood; I might be trying to find one that has knots in a particular spot or has some other feature that will work with my idea.

I am always thinking of different things that I want to paint and I often make little lists of ideas so I never really have painter’s block. I can wake up and have five ideas ready to go. There might be a theme that I’m working on like the gangs or the kids atop animals or fairy tales or something new.

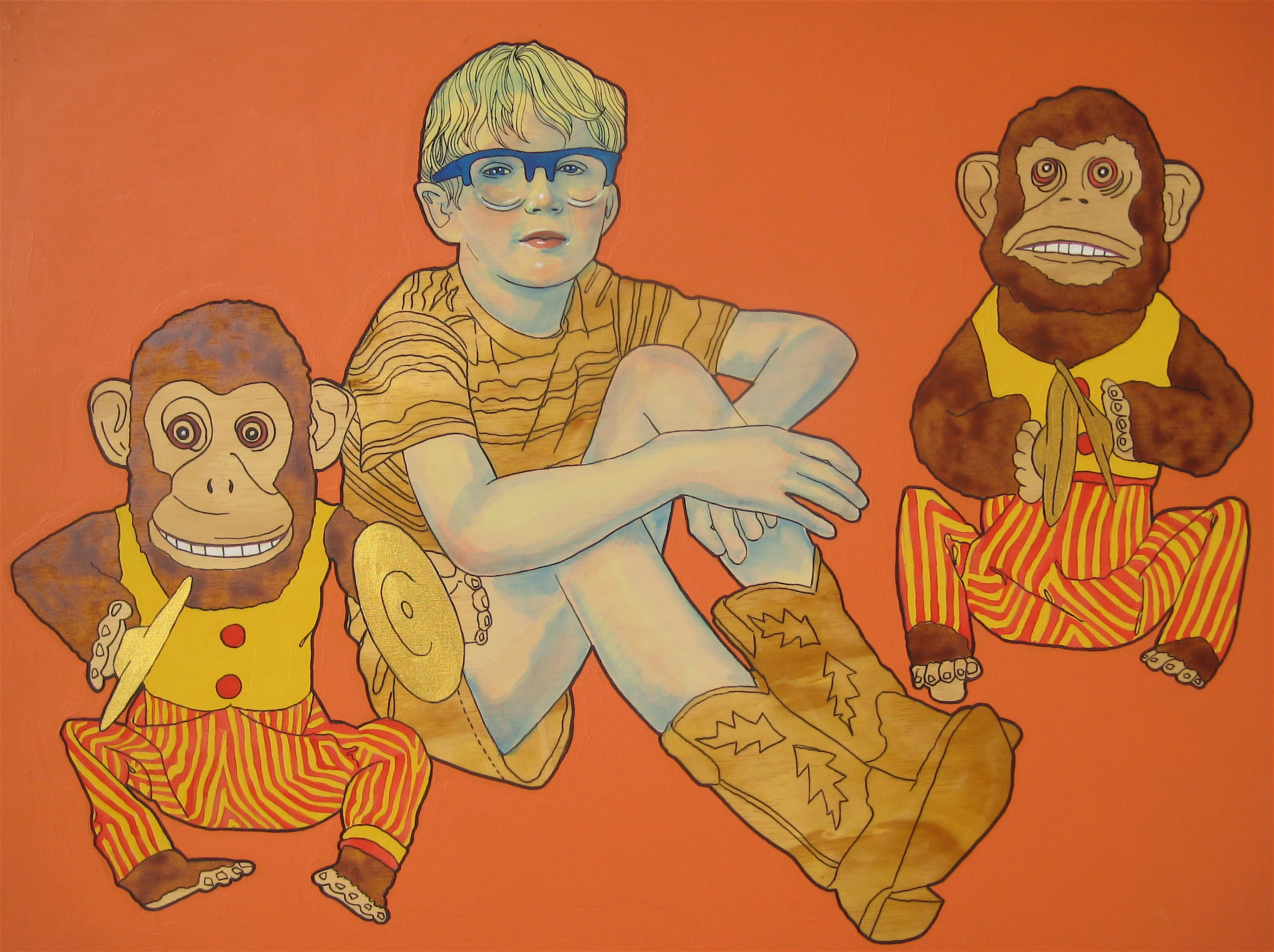

Dance Monkey, Dance!

So it’s quite a spontaneous and intuitive sort of process. I’m guessing you work reasonably quickly?

I basically have ADHD so I get bored working on the same thing too long. That’s why I love using acrylics because they dry in no time. I paint five days a week pretty much every week and it’s not unusual to have five paintings a week come out of it. So I’m a fast-worker, which is largely thanks to the time I spent in Paris as a portrait artist and grew accustomed to painting for eight hours a day.

I think being prolific makes you so much more confident; you can just go for it. I definitely am not a tortured artist who has to get all twisted up to express myself and agonise over every brushstroke. For me it’s all a pleasure and if a piece just goes completely to shit, I can always burn it and roast marshmallows on it.

So I’ve never stressed too much about “wrecking” anything. I guess I sort of feel like if I stuff it up, I can always paint another one. And after doing portraits for so long my technical skills are reliably strong. Strictly speaking, I no longer ‘do realism’. But I still revert to the classical techniques now and again.

Singing in the Dead of Night

There certainly is evidence of these old master techniques in the way you portray your muses, who typically happen to be children.

It’s true that almost every painting I’ve done is of a kid that I know. I used my youngest son as a muse heaps. I loved how his personality emerged in the paintings. Then I started finding other kids in my neighbourhood. The little girls look like little gorgeous angels, but they talk like truckers and have attitudes to match. I find them so hilarious. I do have a couple of muses that are much dreamier and their personalities are reflected in the paintings.

I really do love capturing this moment in time where you have inadvertently interrupted their imagination game and the giant pig hasn’t had time to turn into a chair and the wolf hasn’t turned back into a stuffed teddy. The kids always look a bit annoyed because they were having such fun and now you are looking at them. One of my muses said she loved how my paintings were all bright and cheerful and looked so happy but the kids were never smiling and there was probably something darker going on. She pretty much hit the nail on the head. Playing is serious business!

Images courtesy of the artist.