Horseplay on Brühl Street

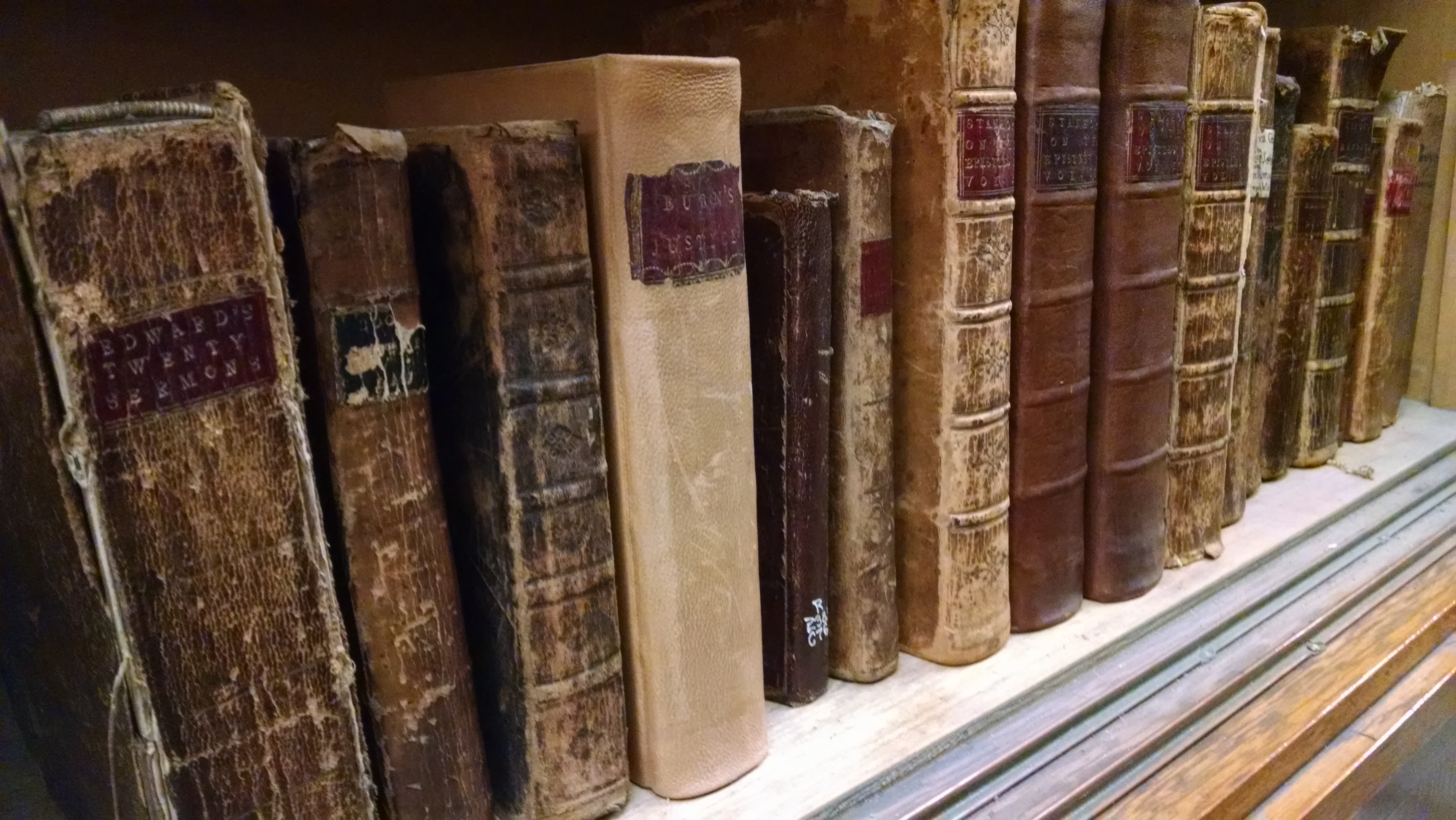

the smell of old books

There exists a certain type of person that, in the presence of company, earnestly claims to adore the smell of old books. In his thirty years as a Professor, Felix K had never chanced upon a mortal with gall enough to admit that the musk of seasoned parchment made them perfectly ill. So common was this universal idiosyncrasy, in fact, that it was not in isolation that K had watched a young scholar eat the pages of an old text as if it were the most natural thing in the world (the belief was, it transpired, that one could altogether taste antiquity in the resinous fibres). Despite years of chagrin, denial and shame, K had always found himself returning to the grievous truth that old books harbour mould.

So unpleasant did he consider the contour of aged paper, in fact, that it was sometimes the case that scent alone would render him virtually incapable of entering the library.

Despite a seasoned academic career, it had taken K twenty-six years to realise that his revulsion was not a matter of books, as of those that were book-ish. Breathless, fierce, undignified types whose vanity for first-editions had an ugliness and baseness that smelled of strong pepper. What he wanted, what he really would have liked in all those years, was a real Prince Myshkin type; some perfect little small-fry who had the courage to call up mildew when he saw it.

So occupied were the Professor’s thoughts one November evening as he returned home on the shuttle. Despite the rain outside, the carriage was warm and oppressive. He navigated his way to an empty table seat where two young students sat in animated conversation. He did not immediately identify this as wretched luck, because last week he had been paired with a man who intermittently sniffed at his hair. The train rolled away from the platform and K settled back into his chair. His mind still engaged, he studied every face in the carriage and wondered. Was there a single honest soul amongst them? Was every last one of them a perfect scoundrel? As the train sped on, he shifted restlessly and, at length, became aware of the spirited exchange that occurred next to him:

“I’m not saying that Werther doesn’t feel –” a thin, horsey girl was saying. “All I mean is… I don’t know. He’s just got no business being sad.”

The boy nodded judiciously. He looked weary and grave as one overtaxed by the ample fruits of his intellect.

“I suppose he’s interesting in a wholesale kind of way…” She continued reflectively. “But he’s not, I mean, ma-jest-ic… you know, in a Louis Wain sort of way.”

“I think he’s perfectly odious.” The boy replied with a breezy solemnity that impressed her. “A positive urchin.”

Her quivering lips moved silently as she tried to find the exact words to express her alliance on the matter.

“Frankly I’m sick to death of people who get steamed up over a little pathos. Who gets hysterical when a dear little peasant child turns down your last Kreutzer? No one.” He shrugged his shoulders in imaginary diffidence and affected a coy little grin that reeked of “shit-hot”.

“For instance, I read this article the other week. I forget where –” He brushed his hair back casually. “The Economist or something…”

The girl beamed. Somewhere in his spleen K grimaced.

“Anyway. There was this piece on Chaplain Tappman; you know, Heller’s holy mess. The author was a real card, saying how everyone ought to downright cherish this guy because he’s one of literature’s only true-blue exemplars of God.”

The girl did not altogether know what he was getting at, but seeing his lips form a smirk, she scoffed loudly and engineered a tinny little laugh. K watched as she briskly tugged at her shawl, pulling the tussled ends as if to conceal some vulgar trinket about her neck. The boy did not notice and looked pleased with the reception.

“The penitent man doesn’t have time to kneel when there’s a rifle pushed up against his snout.”

They tittered over the witticism and, both a little pink in the cheeks, squinted out the dark window looking rapt and altogether pensive. At length, the girl turned her gaze back toward the boy, slowly and deliberately blinking a pair of wise, reflective eyes that pined for endorsement. They gazed at each other searchingly and K wondered if they were comparing respective weltschmerz.

“Say, you know what I love?” asked the boy squarely. “You know what really gets me? That gorgeous knock-out of a smell you get in old bookstores. I could go crazy for it.”

A noise like the whine of boiling teapots began to whistle in K’s ears and he grasped for the arm of his chair with clammy hands. He began to sweat lavishly and unconsciously grind his teeth. The train had begun to slow and, with trembling arms, K struggled to stand against his listless knees. Colliding with a young man serving tea, he groped dumbly for the exit, his aching head now hammering audibly. Reaching the passage, he stumbled through a pyramid of bags and, reaching the doors, retched savagely in the face of a kindly gentleman. In a state somewhere between existence and annihilation, he staggered on to the platform and drifted weakly through the row of narrow barriers. His clothes were damp and his eyes were wide and black. He heard the steam hiss behind him and all at once and for no reason he remembered a line he had once read in a book: ‘Constant dripping hollows stone.’

“Hey mac, need a ride?” A taxi-driver whistled nearby dragging coolly on a cigarette. K turned and sniffed miserably, his resemblance now so much like a domestic cat that the driver looked vaguely about for a copper bell. He handed the man a twenty and resigned himself to the back of a beat-up Lexus. He closed his hot, tired eyes and snivelled.

“Seatbelts, sweetheart” cracked the driver as he secured the door. Turning to reverse, he surveyed the strange customer with amusement. What he observed as horseplay, another might well have observed as plain, unadulterated suffering.

“Where to, Mr?”

K opened a single languid eye and thought. “Anyplace” he said. And then, “Brühl Street”.

The car wound through the dark city streets, the rain lightly tapping at the glass. He gazed out at the black sky and wondered in all virtue and earnestness if he had any tendency to neurosis. Up front, the driver whistled along with the Tennessee Two, blowing intermittent bubbles with a stick of gum. He drummed his fingers on the steering wheel and K noticed how, despite the whole hopeless truth of it all, he looked at ease. He was loutish and artless and for the first time in thirty years, K recognised a man with pluck enough to be an outright nobody. He could say a goddamned thing and this cat wouldn’t care a dime. The fact was startling. He sat idly for several moments and, with a burgeoning sense of knowing, he leaned back and grinned.

“No, the penitent man does not have to kneel”, he thought, and in a moment he was snoring.