With only two plays, the Mount Oswald programme of the Durham Drama Festival was surprisingly eclectic both in terms of form and content. The night began with a myriad of characters depicting the hectic life of Maria Montessori and Stefan Zweig and ended with the powerful introspection of an actor standing alone in a post-apocalyptic world.

‘The Children of Yesterday’, by Enzo Lebeau

One thing about the play that struck me was how well-researched it was. Clearly, Enzo Lebeau knew what he was writing about. The audience could sense how important the historical figures were to him, and the great writing— all the more impressive when we know Enzo Lebeau’s native language isn’t English— reflected the immense amount of work and passion that was put into the play.

However, I can’t help but think that this project was too ambitious for a drama piece and I wish it had been a little less concerned with fitting the whole history into the play, and a little more with theatricality and actually engaging the audience. Indeed, the first part was more of a list of facts thrown at us and hard to follow, especially if you did not know the chronology and events that were mentioned. Perhaps somewhere along the way, the director forgot that a play is a story and not history, that the characters are supposed to move us not inform us, that it’s a performance not a declamation. It brings us to the text. By itself, it was undeniably beautiful, but an overwritten text is a pitfall because it often obliterates what is at the chore of a performance : interaction, with the other actors, with the text. Although the performers were committed to their bit, I failed to see any chemistry on stage and I felt like sometimes they were waiting for their partner to finish their sentence. Moreover, with lines that said everything, what was left for them to convey? They did their best, by nodding, staring vacantly into space and frowning, which was convincing at times, but not enough.

Were they overtaken by the text? I don’t think that was the ‘problem’, as the performers knew it like the back of their hands, but rather that it was unfit for a drama performance. Enzo Lebeau is undoubtedly a talented writer, but he is new to theatre and still needs to find himself as a dramatist. I think the play was a little dragged out, and the last twenty minutes felt like an unnecessary surplus overly guiding the audience towards a higher meaning they could have deciphered by themselves. That being said, I do see this first piece as promising : with that kind of passion and skill— when it comes to writing anyway— it’ll be easy to work towards a second play which will be fully and evenly beautiful. After all, in all the frenzy, and perhaps a little by accident, we find time to grow attached to the characters.

The main reason for that was Daisy Summerfield whose portrayal of Montessori as a driven altruist— paired with Lebeau’s incredible writing— was one of the few instances where every element was perfectly balanced and the result was truly moving. I found Keerthi Vasishta endearing from the very beginning as a melancholic intellectual lost in a world that keeps on rejecting him while Jack Paul’s charisma allowed him to go from dictator to traitor. As for Nathan Jarvis, he easily went from son to father and even intellectual. The choice to have the performers in multiple roles, although it added to the complexity of the play, was a challenge, but it ended up being a success.

Overall, ‘The Children of Yesterday’ lacked a little focus as well as theatricality to make it fit for a stage performance, but this first experience with the undeniable talent of Enzo Lebeau are encouraging and make me eager to see his next play.

‘Stage’s Fool’, by James Murray

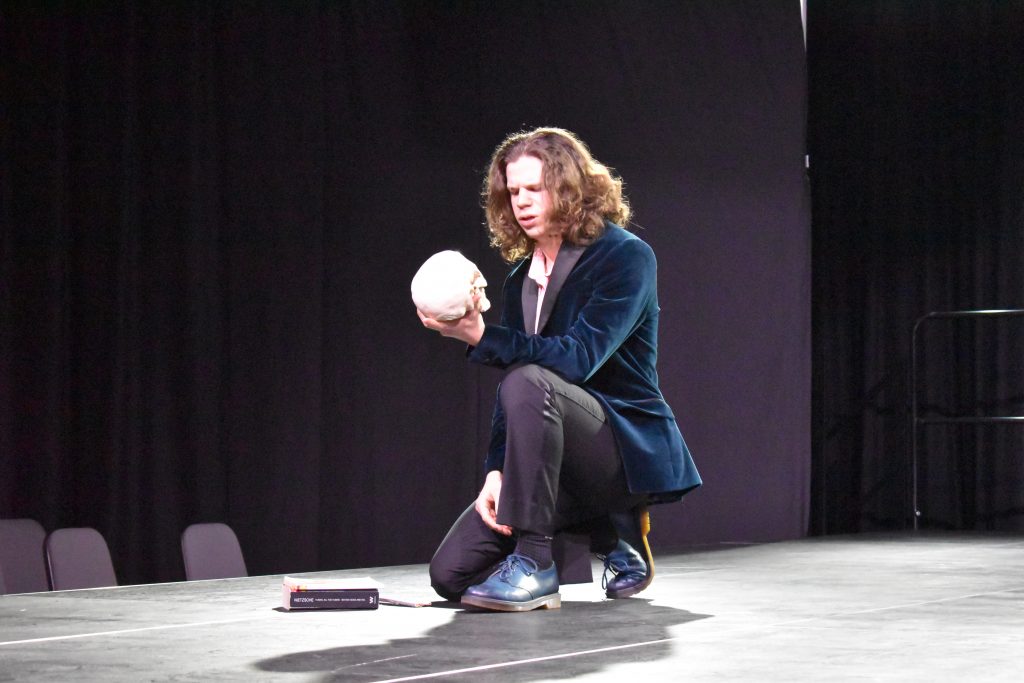

This play, almost entirely performed by Charlie Howe, was a magnificent piece of meta-theatre and introspection, reflecting on what it means to be a performer on stage. The skull— which, in a drama performance, screams Hamlet— and the crown— King Lear— respectively on the left corner and right corner of the stage set the tone. The post-apocalyptic context allowed this mise en abyme where the writer— James Murray— as well as the director— Ben Johanson— played with the idea of the fourth wall. Indeed, some lines were particularly funny to me, like ‘Why should I bother if there is no one to praise me, to review me?’, mostly because I was indeed there to review, and in this case, praise. He coming down the stage to take a chair from the audience was a clever way to maintain yet shake the line separating us from He, the line of reality. Charlie Howe and He blurred into one entity, the Performer, while I, the audience, became invisible. There is something utterly beautiful about an actor monologuing about the threat of otherness in an empty theatre, therefore witnessing such an intimate moment is odd, disturbing, humbling.

However the strength of the text wasn’t its deepness or theoretical aspect, its cynicism, but its humility and humour. In all the chaos— or should I say the weirdly non-chaotic theatre in a time of Armageddon— James Murray introduced absurd elements— a box of cupcakes and intermissions with a voice reading passages from Dante’s Divine Comedy. The off-stage voice was not as redundant as it could have been and actually made me laugh, although it might have been because it was broken and husky and it contrasted with the seriousness of what was being said. The show climax was the appearance of a divine figure eating a cupcake, cruelly indifferent to the character’s pain, inferring his hypothesis : he was in hell, all along. Perhaps the ending was a little forced on us, perhaps it could have ended with the character crying on the floor, perhaps. But what was a weakness in the text became, luckily, a success in the performance with just the right amount of cruelty and disdain.

Needless to say this witty, funny, insightful text couldn’t have been so exceptionally fascinating without Charlie Howe. Performing comes so naturally to him, it was so believable, that I could have sworn he was He. Murray’s physicality, his nervous pacing, his jumps, his face expressions were always spot-on, never too much. Not to mention his mastery of long pauses, and silence. He— yes, the confusion between the character and Charlie Howe is intended— was confident, maybe a little arrogant but just enough so he was still charming, and his rambling was typical of the actor full of himself. Could it be why he ended up in hell? In any case, He, as he put it, had the audience in the palm of his hand.

If I had to sum up, I would simply say that ‘Stage’s Fool’ completely swept me off my feet.