‘Why is it that you can’t hold black people and white people to the same standards?’

‘People only stand up for us when [racial abuse] is finally inconvenient for them.’

‘People fear what they don’t understand…so they profile us as criminals.’

‘They want me to get angry so that I can fit their agenda of being aggressive.’

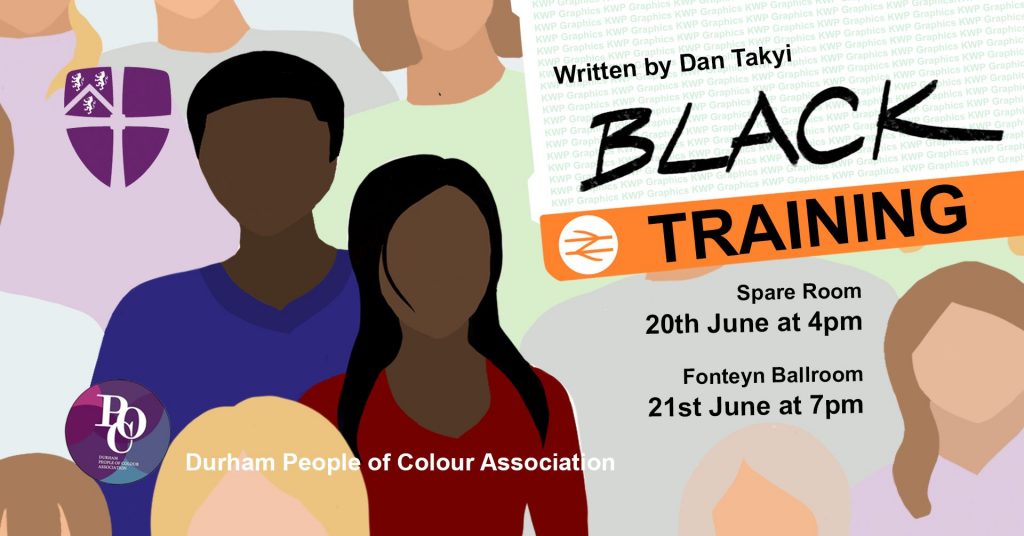

Written by Dan Takyi and starring Andrew Karamura and Tasmin Martin-Young as Jeremiah and Maleeka, ‘Black Training’ raises important points about racism, however at times the production doesn’t always do the well-written script justice. It is a Durham People of Colour Association collaboration and is directed by Luke Blackstock.

In his writer’s note, Takyi stresses that the play is about everyday experiences. The fact that it is composed of personal anecdotes, from himself, his family and a friend is incredibly moving. In order for this everyday nature to be communicated, it must feel realistic and the actors must act with an enthusiasm to bring about change. Yet pieces of plot are tacked onto the end of sentences in a way which feels clunky (for instance when ‘bro’ and ‘sis’ are used to establish the relationship between the two characters). The language of the conversations is not conversational but suited much better to the pieces of spoken-word which they are interspersed with. The piece becomes stilted when it feels as though the words have been forced into the formats of a conversation, and important points are rushed through too quickly. This is disorientating and does not give the audience enough time to consider the implications.

Indeed, Andrew Karamura as Jeremiah comes to life in these spoken-word pieces, and it is a wonderful idea to intersperse them throughout. They deserve more stage-time as they are very effective. I would also welcome a more marked difference in the performance of these pieces––the piano music and change of lighting do not differentiate them enough on their own.

The lighting often distracts from the performance, as oftentimes faces are in shadow. This could pass as an effective creative decisions at times, but it would be a surprising one in a play which aims to reveal and confront people’s hidden assumptions. Only the lights on stage left are used and they fall too low. At times they are dimmed for no apparent reason, whilst the stage remains brightly lit during some scene transitions which makes them seem unpolished. More work on the actors’ stage positioning, or different lighting choices would go a long way in improving the overall feel of the piece.

The train passengers all act very well, however they are portrayed with too little sympathy given Takyi’s insistence that these people are not racist. Despite Takyi’s aim, it is difficult to put ourselves in the place of such one-dimensional characters. Whilst Takyi does well to present what drives people’s ‘racist cogs’ (self-preservation and feeling hard done by, for example), the passengers justify their behaviour too aggressively and are too unflinching in their racism to lead by example. The idea is, after all, that many acts are unintentional and must be challenged. Maleeka and Jeremiah only scoff and roll their eyes, and the train scene becomes too confrontational. It is very hard to imagine any reconciliation.

The ending is very touching, as everybody involved in the production appears on stage and reads true stories of racist attacks on campus. When cast and crew exit, the lights stay on as nobody is left to control them, and this time it is a nice touch; we leave the theatre knowing for certain that racism is still very much alive.

‘Black Training’ continues for a final performance in the Fonteyn Ballroom, Friday 21st June at 7pm.

(Images courtesy of Durham People of Colour Association)