‘…the humanity of this piece was beautifully represented by all involved’

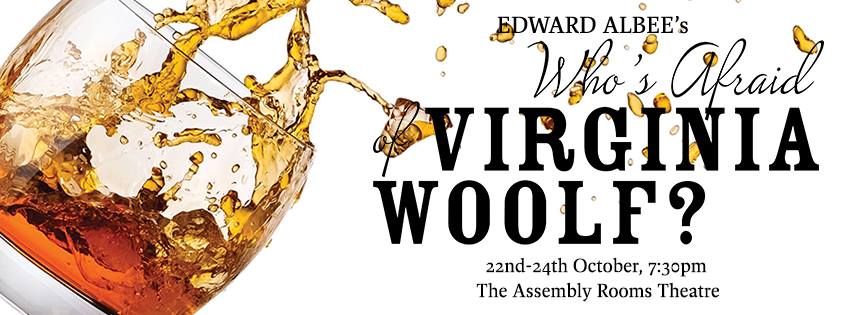

Last night marked the opening night of Fourth Wall Theatre’s production of Edward Albee’s famously and tantalisingly ambiguous play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Like most members of the audience I went along with very little knowledge of the plot of the play; after the final curtain I still wasn’t entirely sure of everything that had happened. Confusing, and intentionally so, the foursome cast ebbed and flowed with the moments of understanding and insanity in the play.

From the outset, it was a fantastic display of the many layers within the play. In the opening scene, Sarah Slimani (Martha) played the irritating and provocative wife to such an extent that the audience felt her husband’s exasperation and annoyance. The tipsy, half sleepy ramblings embodied the full and ever-changing ranges of emotion that Virginia Woolf herself used in her stream of consciousness technique, and it was incredible how Slimani never seemed to falter from her rollercoaster ride of feeling.

In contrast, Sasoon Moskofian (George) seemed slightly out of sync with his character at first, with signs of self-conscious acting. He soon warmed up to the role, though, and by the second act was in full swing, making the character’s lines seamlessly his own. Dragged along with the other three characters, the audience could only watch as Slimani seemed to draw all attention and energy towards her. This I have to attribute, as well as to Slimani’s acting, to the staging of the play.

The different levels of furniture on stage (the differences in height between a couch, a chair and standing) allowed each character, at one point or another, to be placed on another level to the rest. The play itself is rife with hidden meanings and different levels of conversation. At times it seemed as if Martha and George were having a conversation on an entirely other level to that of their guests. By seating Martha and George at either end of the stage, the director managed to split the stage into the internal and external conversations of this couple; the external conversation with their guests and underneath their own internal debate.

This staging also succeeded in dramatising their back and forths, much like a tennis match. All four actors had impeccable timing in these repeated sparring matches, and although sometimes changes in action seemed slightly too sudden, interruptions in dialogue flowed seamlessly and left no awkward pauses between lines. Perhaps, although I am aware that the characters are supposed to be drinking, it would be necessary to enunciate some of the quicker lines more so that whilst retaining the speed, the content of the lines is not indistinguishable to the audience.

Obviously, as well as delivery of lines, the play’s success relied on the way the actors presented their characters’ emotions through body language. Like with many plays of this kind, what is not said is as important as what is said and the foursome made great use of physicality to express this. For example, there was a blatant physical tension between Adam Simpson’s Nick and George. Whether intentionally or not, I loved how at points in their conversations the pair mirrored each other’s actions, leaning backwards and forwards in response to the other’s movements. For me this epitomised the jostling between the two men for some kind of masculine superiority over the other. This body language also introduced a threatening element to the scene, revealing the veiled aggressiveness beneath their lines. By increasing this mirroring effect, the actors would be able to highlight the similarities between the two men, whilst still remaining opposites of each other. This would be particularly useful midway through the play when the two begin to acknowledge their similarities and their hostilities soften slightly.

Similarly, Lydia Feerick’s (Honey) body language in the later acts demonstrated when she is, at moments, outside of the action altogether. While on stage, Feerick managed to retain elements of voyeurism and seclusion in her acting. It was a wonderful externalisation of the audience’s own feelings of wanting to look away but being unable to tear your gaze from the carnage of relationships on stage. Honey is both a participant and viewer, and the staging in those scenes was particularly effective in highlighting this.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is, undoubtedly, a very difficult play to perform without losing any of its superb, hidden meanings and threads of unconscious nestled and woven through the surface action. Yet in my opinion Fourth Wall Theatre and its perfectly in sync foursome did justice to this brilliant piece. I was left with haunting and paradoxically affectionate feelings towards the plight of the human existence. As the director wrote in the programme, “this is not a sad play. It’s a human play”, and the humanity of this piece was beautifully represented by all involved.