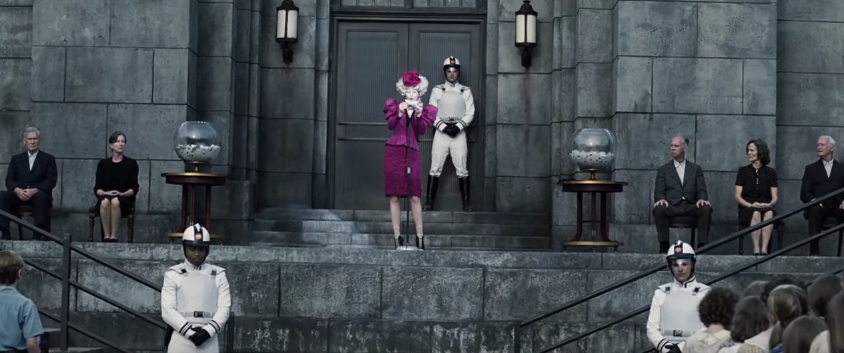

Perspective and scale in shots show how characters’ experiences are contrived by the political ‘game’ above them.

Having found Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games books enjoyable but fairly unremarkable, this film series has been a consistently wonderful surprise. Expecting just another sentimental experience that smelled just too strongly of teen fiction, the first Hunger Games film broke my perception. It was a highly atmospheric picture, able to present subtle hints about the political undertone which was to follow later in the series: the first sparks of revolution across the districts of Panem.

For any newcomers to the series, the basic premise of Suzanne Collins’ world is a post-apocalyptic North America divided into twelve enslaved ‘districts’ whose people work in near-starvation, ruled over by the decadent, superficial ‘Capitol’, whose sinister properties go far beyond suspicious spelling. Naturally rebellious Katniss Everdeen from District Twelve gets roped into the terrible ‘Hunger Games’ in order to save her sister, and is made to fight twenty three other children to the death, for the entertainment of the desensitised Capitol citizens – like Bake Off, and no less aggressive.

Director Gary Ross collaborated with Collins and co-writer Billy Ray on the film’s screenplay, which added to the story pre-emptive traces of the series’ politics: most significantly, a number of scenes within the Capitol, showing dialogue between the President Snow and the head ‘game-maker’, Seneca Crane. In an enlightening interview, Ross has spoken of his purposes for these scenes: to create a tension between one generation in the Capitol who knew that the games ‘were actually an instrument of political control’ and another ‘successive generation… enamoured by… the spectacle that was subsuming the actual political intention’. This device absolutely works, providing a layer of wider societal context to Katniss’ story, as well as letting us into the minds of characters who in the novel are barely explored by comparison. Ross believes that it is individual people, with ‘an individual understanding what they will and will not tolerate’ who bring down oppressive political systems; it is natural, therefore, that he has interpreted a personal story of Katniss’ endurance into a more overtly political film.

Ross’ idea of the ‘individual act of morality’ sparks rebellion in the districts.

As well as expanding the content, Ross’ film made stylistic changes to The Hunger Games which transformed its tone. Katniss’ first-person narrative in the novel is replaced by an obviously third person narrative in the film, which means it escapes from the perhaps overly introspective tone of the book. But importantly, the film’s narrative maintains the ability to focalise on the character, and often depicts events as though through Katniss’ eyes: the use of shaking cameras and washed out colour in wide shots interprets Collins’ verbal internal monologue into a monologue of visuals, which still communicates emotion and vividness to the audience. In short, the film is simply better, more widely written.

Focalised cinematography and colour contrast are used to alienate the superficial and ignorant Capitol character in the grey world of poverty in District 12.

The second instalment, Catching Fire was another step up. The new director Francis Lawrence could not have better carried the flame of what Ross had began to build in the first film. In Collins’ second book, the trauma of Katniss’ experience in the games, and her resulting heroism, which Ross describes as her refusal in face of death to participate further in the games due to realising her own empathy, is overcast by lengthily described confusion about which of two romantic admirers she feels the most affection for. In the film, this ‘Twilight section’ of the story is sidelined, and in its place, the sheer devastation of Katniss’ life and wellbeing is emphasised. The colours are grey; again the camera wobbles with subtle focalisation to the character, where in the book a present tense first person narrative simply tells rather than shows. The film shows Katniss not as a character with too much to cope with in her love life, but as a character with nothing. Jennifer Lawrence’s performance on this aspect is on point: she plays a hero who has been broken before the film even starts.

Politics is brought into fuller focus in the second book, opening with direct threats from President Snow, a clear confession that his system is unstable, and finishing on the climactic realisation that this year’s head game-maker was an inside man, and Katniss has been drawn unawares into the beginning of an imminent rebellion. Structurally, the film had only to capture the intense pace and intrigue of this story, as well as the inventive clock island of Collins’ ingenious design, which, aside from its perfect suitability to the big screen, serves as an important turning point in the plot: the realisation that control of events has slipped out of the hands of the Capitol and fallen into those of the rebels. Perhaps the best-timed moment, another point of no return, is just before Katniss is released into the games, when her subversive stylist is beaten to near-death, deliberately before her eyes. Cleverly, the film sticks close to Katniss’ perception, but focuses on the elements of mystery which she half sees. Politics is not an undertone as in the book, but an overtone, the wind in the air around the main storyline.

The world of the characters is on a vast and real scale…

…Yet everything is shown to be artificial, and the characters manipulated.

In the even better third film, Francis Lawrence constructs a detailed and intelligent picture of the sentiment and actual mechanics of revolution; it is a film primarily about the nature of political power and the processes by which this changes hands. It is not that the focus moves away from Katniss, but away from her introspective monologue and teenage drama, and towards her exploited position as a political puppet. It is the scenes away from Katniss which provide the most revealing information about her.

The absolute highlight of Mockingjay: Part 1 was undoubtedly the musical sequence set to Katniss’ dark and melodic song ‘The Hanging Tree’, which directly inspires an attack by rebels on the Capitol’s power supply. Katniss begins singing a cappella, is recorded, then musical accompaniment joins the voice. The music continues to hover over a brief scene where leading rebel tacticians, most notably Plutarch, beautifully portrayed by Phillip Seymour Hoffman, discuss changes they are making to the footage. The song is broadcast to the districts, and more voices are heard joining in as ordinary but organised people march on their enemy’s stronghold, and, despite several casualties, succeed. This musical sequence is Francis Lawrence’s real work of excellence within this film. It displays the direct transition from the words of Katniss, the revolution’s figurehead, briefly through the cutting room floor, to the revolutionary action of the oppressed citizens. As Ross said, it only takes ‘one person refusing to play the game, and publicly’. The scene is both inspiring and gritty: it is vital that we see rebels dying without any sense of glamour. The film concerns itself with the big picture, but never romanticises or forgets the lives of individuals and the all-too-real humanitarian effects of violent political action. The ending too, fits the rest of the film’s tone: a ghastly shot of Katniss’ poisoned friend writhing against the chains of his medical bed, while the hero watches, caught as ever between the forces around her.

$

The second half of this book is, for me, a source of both anticipation and worry for the release of Mockingjay: Part 2. Katniss’ total psychological breakdown at the end of the book reads as melodramatic, but the films have fixed this problem before. Katniss’ surprise response towards the rebel leader was, written, a predictable decision. It will hopefully be less so in the final film, as Katniss’ psyche, without the constant thought-stream of the book’s narrative, is in shadow and unpredictable.

The story of The Hunger Games is perfectly suited to film: its geography is cinematic, its characters complex, and its themes of political power, the media, and the thought of individuals are poignant and full of potential. So I raise three fingers in salute to the cast and crew, and hope that their struggle against oppressively bad film is darkly victorious.