Paterson (played by Adam Driver) is a bus driver who writes poems, many of them about his partner Laura (Golshifteh Farahani). In one scene, Laura tells the eponymous Paterson she read that the Italian poet Petrarch wrote poems for a woman also named Laura. She interprets this as a sign that Paterson, like Petrarch, will achieve fame. For her, coincidence is the sign of an alignment in progress, leading to growth. Paterson, far more inscrutable in his demeanour, makes no such assumption, but he is awake to coincidences, even though they never change his life dramatically.

In fact, the film is quite a continuum. Paterson was the title of the five-volume epic poem by the poet William Carlos Williams, and also the name of the character and the city it was based in. Director Jim Jarmusch takes the synecdoche (when a part represents the whole) of man-for-city and weaves a film rich in poetic overtones. In this way, everything in the movie—character or object—stands for itself and something else. On one of his nightly jaunts Paterson overhears an aspiring rapper murmur ‘no ideas but in things’, a line from Williams’ epic. The great poet’s picture is also up on the wall of the local bar. The bartender is called Doc; Williams was a paediatrician. However, in no way must we surmise that the film is about an aspiring poet’s obsession with a great poet.

The film spans an undramatic week in Paterson’s life. What is discernible, however, is his deep immersion in the everyday: going to work, driving a bus around the city, and coming back to a woman he loves dearly. His relationship with Laura too remains steady and does not oscillate high or low. He seems content with the mundane cycles that make his days. Cycles. Circles. Now that’s something you get a lot of in the film: the cycle of days. He drives the same route, has lunch at the same spot, and visits the same bar each night before bed. But no circle is identical. He never wakes up at the same time, he picks up different passengers every day, eavesdrops on different conversations, writes something new at lunch, and encounters different characters at the bar. Even Doc is in a different mood each night. In one reflexive moment, Paterson admires some curtains on which the artistically inclined Laura has painted: “I like how all the circles are different.” Jarmusch’s masterstroke is how he successfully constructs a metanarrative within the film, one that is always open to commenting on itself as a text.

Whilst not about circles, Jarmusch’s film meditates on the mundane life of a bus driver, revelling in the endless cycles of both Paterson’s life and thus through him our own lives. The striking feature is the Zen-like contentment of Paterson so adeptly portrayed by Driver’s understated performance. The everyday does not induce boredom in Paterson because, Williamsesque as he is, he dwells not in ideas but in things. There are subtle shifts in expression which manifest as reactions to life around him, but he keeps returning to stillness, anchored as he is to equanimity. He attends vigorously to life and the things around him, and they osmotically enter his poems, be it a box of matches, the windshield wiper, or people.

The result of such a deep engagement with reality induces a dream-like fluidity in the film. There is a meandering quality in the juxtaposition of shots in the film. Jarmusch, acting against Hollywood traditions, is not driven to make a statement. The sequences where Paterson writes a poem turn supple in tone with languorous dissolves, where often more than two shots are superimposed creating a distortion that does not jar. This is accompanied by an ambient electronic score, composed by Jarmusch and Sqürl band-mate Carter Logan. This complements the soft oneiric texture of the visual content. Just like the images, the notes are suspended in a perpetual state of blending.

Adam Driver and Golshifteh Farahani as Paterson and Laura, respectively. (source: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt5247022/mediaviewer/rm2316243712)

Like circles, dreams abound in the film. Perhaps it is circles that cause dreams, as the drudgery of routines do, or maybe it is the dreams that are themselves cyclical, returning us always to waking. Laura tells Paterson about her dreams when she wakes up. She has many dreams—to be a cupcake seller, to be a country musician—and Paterson is forgetful since she has so many. He is not wholly attentive to her dreams. He, it often appears, is daydreaming; in paying attention to things he is distracted from ideas.

The storyline is distracted, to say the least. Every time Jarmusch seems to get a grip on the written plot, it runs away from him again soon after. For example, there are red herrings everywhere. The plot keeps doubling back on itself and stop-starting from beginning to end. Nothing comes to fruition. Nothing much ever happens. And Jarmusch is not unaware of this. In an interview he speaks his interest in “minimalism” and of the film as “intentionally slight”. He calls the scene where the bus breaks down his “big action scene”, one where an interruption he works in doesn’t evolve into a bigger sequence, remaining a minor inconvenience at best wherein nothing really happens. He does this repeatedly, as again when out walking Marvin, Paterson is warned of dog-jackers by four men in a car, but nothing comes of it.

In a similar scene, when Paterson is at the bar, a woman sits next to him and the bartender Doc introduces them. A drama-literate fan would expect sparks and then trouble in paradise. The two are almost immediately interrupted by the woman’s jilted lover. She walks away. There is not a glimmer of hope or dejection in Paterson. He is water; nothing leaves a mark. So subtle is Jarmusch’s artistry that I can almost hear him chuckle. I’m not sure he even intended to evoke such an expectation and then tread on it. But that’s what happens when there’s nothing. You look to fill the empty spaces. In the absence of the helping hand of a director there’s only you, the audience. Perhaps this is what the film is about: us. Me. You.

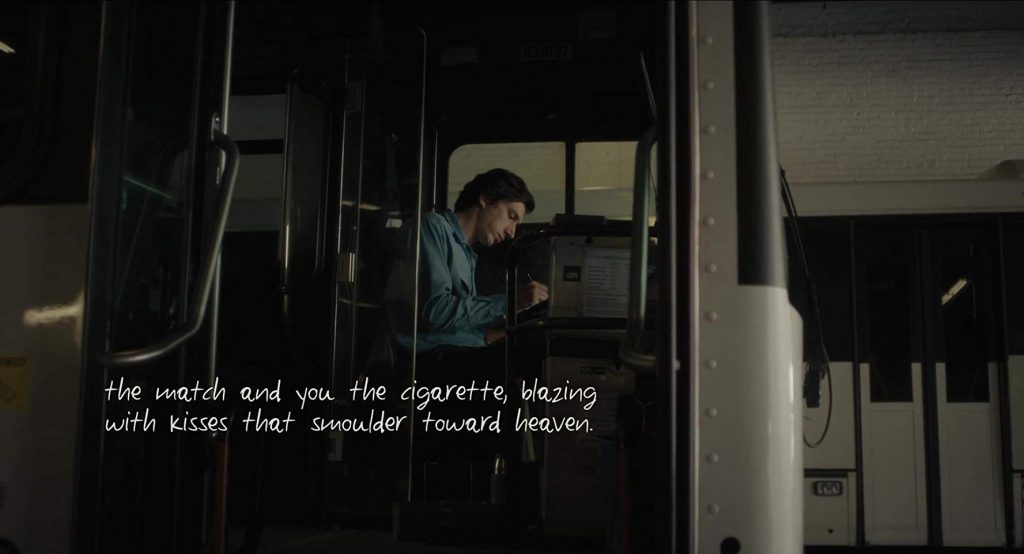

Adam Driver as Paterson, hard at work writing his poetry (source: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt5247022/mediaviewer/rm3585562112)

Jarmusch has often confessed his love for the New York School of poets, one of whom, Ron Padgett, wrote the poems that feature in the film. Many New York poets, like Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery, big influences on Jarmusch, were deeply influenced in turn by W. H. Auden, who famously said, “poetry makes nothing happen.” Poetry may be inadequate if you want to make grand changes in the world. It makes nothing happen, but in Auden’s statement we hear more: it is the intention of poetry to make nothing happen, to make a nothing that is palpable, a thing in itself. A poem is an empty thing because it contains no explicit meaning, only various possible interpretations, which lends it the illusion of being a thing. As readers we immerse ourselves in the vacant space of poetry and fill them with our interpretations, making the nothing become a thing. Jarmusch deliberately makes nothing happen in his film, and through the tools of cinema invites us to participate, to make what we can of nothing and know that whatever we make is a reflection of ourselves, our own poem.

Something happens at the end of the film. There are more circles. I spoke to a friend a couple of days ago and asked her what she found. She, an avid consumer of horror films, said she found it “boring”, and was disappointed that “nothing happened in the end”. Zero adrenaline. In fact, Jarmusch says “I’ve tried to make films that are not shouting out from the mountaintop to all of the world, like little letters out to someone I care for.” In his distracted but safe hands we never feel jangled. Maybe “Paterson” is his letter to us. Now remember “bus driver” and “Adam Driver” when I tell you that Jim Jarmusch’s partner’s name is Sara Driver. Whom is the film a letter for? His partner? His Laura? Perhaps. Perhaps nobody in particular. And anybody who chooses to pick it up.