Gavron does not hesitate to depict the harsh conditions under which women worked without enfranchisement

This weekend I went with my college Feminist Society to Newcastle to see the film Suffragette, directed by Sarah Gavron. It opened with shots of a 1912 laundry factory with close-ups of the heavy, backbreaking machinery the women had to handle, the sweat caused by the oppressive heat and the hands tirelessly scrubbing clothes. This set the tone for what followed as the fictional Maud Watts (played spectacularly by Carey Mulligan), whose only solace from the trials of labour and tense marital life is her son, George (Adam Dodd), becomes engaged with the Suffrage movement sweeping the nation.

The character of Maud was largely fictional, as was the thriller-like element of the film, whereby an Inspector (Brendan Gleeson) tries to infiltrate the movement through following Maud – though this did not detract from the perceived authenticity, as the government did employ such agents. One cannot deny Gavron’s shameless emotional manipulation of the audience as Maud’s marriage to Sonny (Ben Whishaw) falls apart. Yet, even as I wiped the tears away, I was struck by the undeniable truth behind Mulligan’s heart-wrenching performance which showed just how much the women suffered as they were shamed by husbands, fathers, and even co-workers, just for wanting some form of equality.

Indeed, what impressed me most about the film was its gritty realism. Each time the Suffragettes came out of prison they were visibly weakened and fragile – their injuries did not miraculously heal overnight to return to perfectly glossy heroines. Violet (played by Anne-Marie Duff), who drew Maud into action with her rebellious cockney attitude, found herself in an all too realistic circumstance forcing her away from the movement. There were no ‘Hollywood-esque’ soundtracks of melancholy classical music detracting from the grim reality of being a militant, dedicated Suffragette. The scene where Maud is force-fed in prison was particularly difficult to view for this very reason, as the sound of her continued struggle was heard clearly. Likewise, there was no hopeful background music as the Suffragettes crowded outside the Houses of Parliament to hear the response to the working women’s testimonies from Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George; instead the outraged cry of “Liar!” was all the more emotional breaking forth from the tense silence and escalating into the brutal depiction of policemen beating women for no other reason than their audible anger.

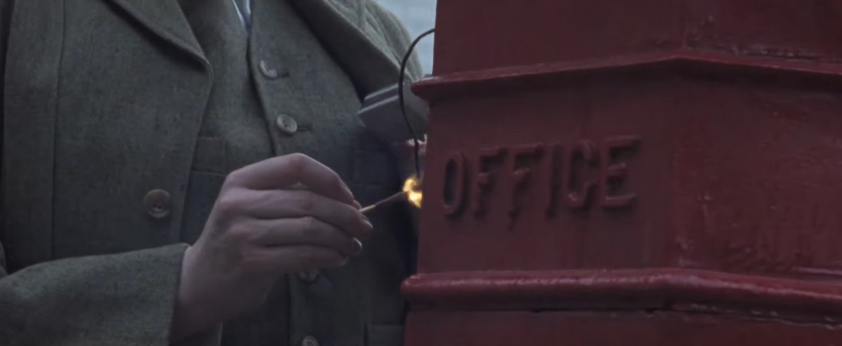

In 1912 Emmeline Pankhurst called on her followers to take up militant action, defying a government who would not respect their patient and peaceful calls for the law to change. Watching the film, I could not help but sympathise with the immense frustration they must have felt as they put their lives at risk performing actions such as blowing up communication links, only for news of their deeds to be silenced by the press, thus obscuring the publicity the Suffrage movement craved. Meryl Streep’s cameo as the leader herself was not particularly notable, given the brevity of her appearance, yet she commanded attention in a way one would imagine Mrs Pankhurst did, remaining composed and resolute, even as the police arrived to arrest her. The visible awe of the eloquent and educated Edith Ellyn (wonderfully played by Helena Bonham-Carter) in her presence, gave a true sense of the importance Pankhurst held in the movement as a figurehead, uniting women like Maud, who had hardly dreamt of another way of life as individuals in their own – and not their male representatives’ – rights.

“It’s deeds, not words, that will get us the vote.”

Suffragette was an impressive take on 18 months of a 50 year process towards voting equality for women in the UK, and watching it made me feel fortunate that I was simply too young, and not the wrong sex, to vote in May. Yet, whilst the voting turnout for women went up by 2% from 64 to 66% in this year’s general election, many women still disregarded the right which was so hard fought for. Only 1% more men voted, showing that disengagement is still too low among the entire population. Yet Suffragette did throw light onto the continuous need to engage women in politics, and while Harriet Harmon’s stereotypically pink bus may not have been the best way, at least she tried. Similarly, the foundation of the Women’s Equality Party in April shows a more bold approach to raising female voices in politics. The historical accuracy may be questionable in some cases, with multiple inspiration for certain characters and fictional interaction between others, but it produced an emotional link to a time where the status of women was incredibly lower than in the UK today. Although, the final scene suggesting an end to women being ignored in politics did leave the uncomfortable awareness that (while of course I would argue that regardless of gender, the leaders of our country should be the best people for the job), there still has not been a female Deputy or Prime Minister since Margaret Thatcher.