Actor Morgan Freeman has criticised Black History Month in the United States.

History, as Napoleon Bonaparte once said, “is the version of past events that people have decided to agree upon.” Needless to say the discipline is certainly subjective. The historian’s task is to sift, arrange, prioritize and contextualize events to produce a narrative, and with regards to Black History Month the effect is to create a somewhat distorted recollection.

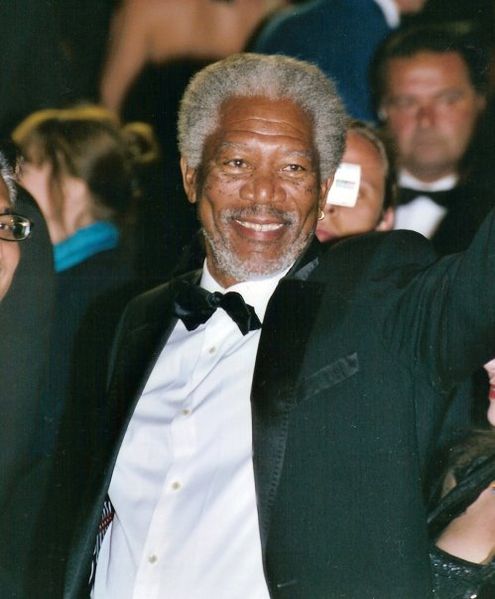

First off, the idea that ‘black history’ can be contained to just one month is not only controversial, but divisive within a United Kingdom that boasts of multi-culturalism. Recalling the words of Morgan Freeman, “I don’t want a Black History Month, Black History is American History,” it is clear that by designating a period of time in which we remember black history it can become diminished or marginalized. Surely instead, black history should be integrated with the remainder of British history thereby signifying its equal importance?

Still, it is hard to argue with the good intentions behind Black History Month and there are many positives to counteract the controversial reception with which it has been met. Begun in Britain in 1987, the original aim of Black History Month was to celebrate the contribution made to this country by African, Caribbean and Asian people. Following a lack of recognition of the efforts made in WWII, with particular reference to West-Indian ex-servicemen, Black History Month has since established a wide educational and historical awareness. It has also, in recent years, laid emphasis on instilling a sense of pride and identity among young black learners. Sir Lenny Henry, for example, has announced he will soon front a British theatre series in support of Black History Month and outlines the importance of reaching young black people; “we acknowledge that the young reach their current heights by standing on the shoulders of those that went before.”

Within Black History Month there is always a generous collection of events to attend, all sharing history as an intrinsic part of their objective: storytelling, comedy, theatre and topical debates are just a few examples. Detail and consideration have gone into almost every layer of Black History Month and the result is a very purposeful event. The month of October, for instance, has been chosen because it is traditionally a period of tolerance and reconciliation in African culture. The Ghanaian symbol of Sankofa has also been adopted by Black History Month and appropriately means ‘learning from the past – with the benefit of hindsight’. As a result, Black History Month has become a way to reconnect with African origins.

Despite this, however, points of contention remain rife. Whilst most are in agreement that the intentions of Black History Month remain conscientious, some have interpreted its execution as lacking, and even counter-productive. If we return to the definition of History as a perspective shaped by a range of influences and experiences that “people have decided to agree upon,” it is easy to see how events created to teach and inform can become distorted.

Notably, there has been a tendency in recent years to focus on the negative aspects of Black History which has a damaging effect on how young people understand the efforts of their ancestors and the culture they originate from. One such example is as follows. During Black History Month a huge emphasis has traditionally been placed on slavery and the obvious horror this entails. Whilst it is true that slavery largely dominates the history of Africans descended from the Caribbean, it would be damaging and inaccurate to assume that all Africans living in 16th and 17th century England were slaves. In fact, for anyone living in Stuart and Tudor Britain to be a slave was not legally possible. Many Africans owned private property and were able to remain financially independent, they were baptized and buried in parishes across the country and even attended queens at court. One such African was “Christopher Cappervert, a blackemoore”, who died and was buried in the St Botolph without Aldgate area of London on 22nd October 1586.

It is clear, then, that Africans were far more integrated into the community than it might be originally expected, and more importantly this is not an element of history that Black History Month chooses to elaborate on. In essence, by focusing too much on the negative aspects of Black History, young people can be left with a very bleak image, thus encouraging racial tension and causing young people to suffer a loss of identity.

In recent years Black History Month has also endured a significant cut in funding and its future appears increasingly uncertain. Since reaching its peak in 2011, with 4700 themed events being held around the country, financial backing for Black History Month has dropped by 50% within London, and since 2012 this number continues to decrease. Some councils such as Camden, Greenwich and Westminster have scrapped their budget entirely. Soon it is possible Black History Month may cease to exist.

Yet if we as a society succeed in recognizing and appreciating the contribution of black people throughout history, perhaps this would not be a bad thing. In an ideal world, Black History Month would not be necessary because Black History would be more fully incorporated into the wider syllabus of English history. Perhaps Black History Month can only really be a deemed a success once it has become redundant.