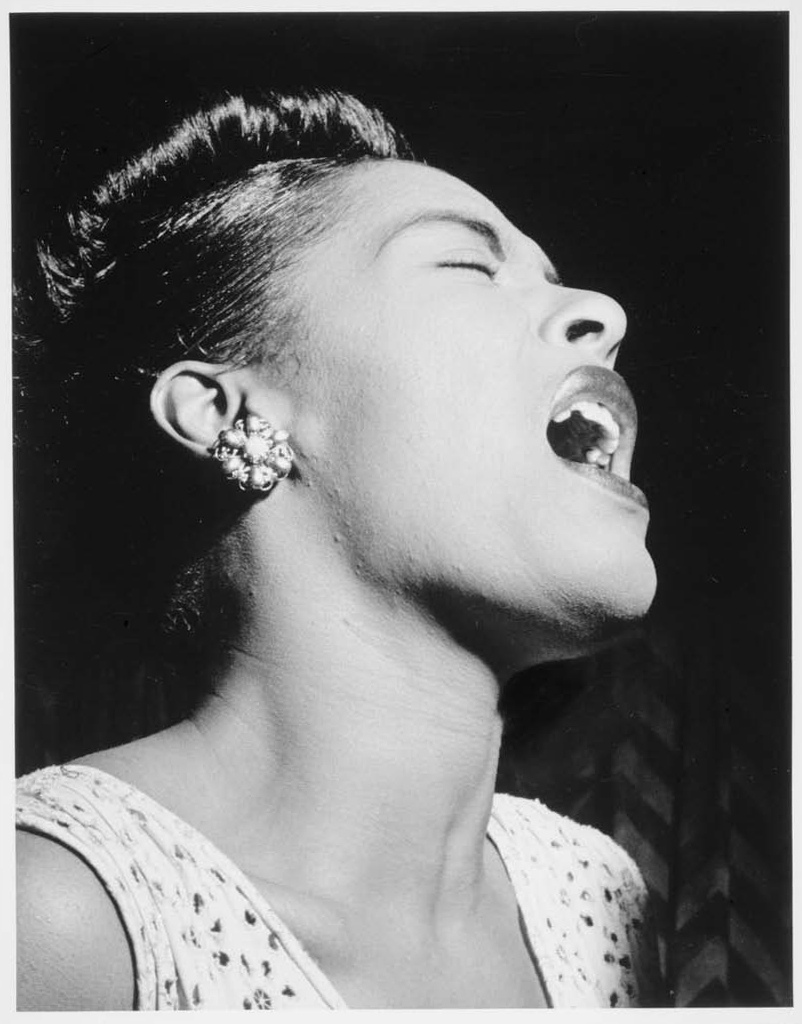

One of the most influential jazz singers of all time, Billie Holiday.

Black contribution to history and culture is all too often forgotten or erased from the history books. Black History Month, which is just drawing to a close, attempts to ensure that the achievements of black communities across the globe are remembered and celebrated. This contribution has had the greatest impact on me personally in the creation and evolution of jazz. I grew up idolising legends such as Billie Holiday, Art Blakey and Louis Jordan, who inspired in me a huge love of the genre. Many of these black artists were crucial in the development of music during the twentieth century, and became some of the most famous artists of their time. Regardless of your opinion of jazz itself, we all owe a debt to its creators, as the foundations of modern music are built on its back. Rock n’ roll, R&B and soul all have their roots in the genre, so if you’ve listened to and enjoyed any mainstream music since the 1950s, chances are you have jazz to thank.

Jazz grew from a distinctively African American sensibility. In the aftermath of slavery, large black communities existed across America with their own heritage and influences. Combining African rhythmic and percussive styles with more European forms of harmony and structure, African Americans created a musical fusion born out of this duality. Jazz was also unique in its focus on improvisation, allowing for unprecedented freedom of expression through music.

However, with its roots in slavery, jazz could hardly avoid being somewhat defined by tragedy and emotion. The Grammy winning trumpeter Terence Blanchard has said, ‘What makes [jazz] African American to me is the pain and suffering, the honesty about our search for truth’, making it more than purely a musical style. The emotional richness of the genre is particularly clear in the work of vocalists such as Billie Holiday, whose expressive singing style made her name. Holiday was revolutionary in embracing the improvisational style which characterised instrumental jazz, and translating it to vocal lines, altering melodies to express pain, joy and heartbreak.

Slavery, followed by segregation and ingrained racism, meant that in many ways jazz is inseparable from the turmoil which has characterised aspects of the African American experience. From its inception, jazz took on a deep cultural and political significance which only increased as it became a more widely accepted and popular art form. By the 1930s, protest songs detailing black oppression came to the fore. Songs such as ‘Strange Fruit’, which graphically describes the lynching of black Americans in the Deep South, were of huge significance. First sung by Holiday in 1939, it sold over one million records and was described by Samuel Grafton in the New York Post as the potential ‘Marseillaise’ of the angry, exploited masses. Indeed, jazz was to develop into an important political outlet for African Americans, reaching as it did across the racial divide.

Not only did jazz become a political outlet for black musicians, but for some it also provided incredible upward mobility and a possibility to transcend entrenched class barriers. For many black musicians, musical talent and the newly blossoming jazz scene offered the best chance of social advancement and wealth in a society that presented very few opportunities to minorities. However, the story of jazz and race is deeply complex. With influences absorbed from Latin America, Africa, Asia and Europe, it has become an exceptionally diverse musical genre. In many ways, jazz helped race relations substantially, with its diversity of backgrounds fostering integration in an era when segregation was the norm – especially between whites and blacks. White musicians were sometimes invited to play in black bands, and within band hierarchies black musicians could be considered superior to their white counterparts as limited meritocracy was able to flourish amongst artists.

This is not, however, the full story. Such seeming equality simply ceased to exist outside of such small enclaves. Jazz in its infancy was viewed by mainstream popular commentators as inferior, partially due to its equation with black culture. This meant that white musicians became crucial in making jazz ‘acceptable’ to the white middle class, often pushing them to stardom ahead of their black counterparts. Famous white musicians such as Bix Beiderbecke and Chet Baker, while undoubtedly talented artists, have often been cited as part of a problem of white domination of predominantly black art forms. Despite white artists being in the minority, they were nevertheless often disproportionately famous due to a commercial need for record labels to appeal to white audiences. White artists such as Benny Goodman gained epithets such as ‘The King of Swing’, while black artists often struggled to be recognised on the wider stage. While Goodman was able to use his fame to introduce the world to the talents of black musicians, the heights of fame were substantially harder to achieve for African Americans, despite their unrivalled contribution to the genre. Black talent was constantly mediated by the safer, whiter faces of fellow musicians, and this makes it all the more important that their contributions are remembered and honoured today.

African American impact on music did not stop there, however. In the 1940s, jazz gave birth to rhythm and blues, which in turn evolved into the cultural revolution that was rock n’ roll. While a whole host of musical influences helped produce this enduring genre, including gospel, swing, and country, it has been suggested by writer and musician Robert Palmer that rock n’ roll ‘was an inevitable outgrowth of the social and musical interactions of blacks and whites…’. Jazz was the first and most influential instance of this musical fusion, allowing new combinations and interpretations of rhythm, melody, and style to emerge from an era of deep racial tension. At its heart, rock n’ roll was a true product of America and its melting-pot nature.

Jazz is a vibrant and living art form, with artists continuing to create endlessly relevant music to this day. But the legacy of those early musicians also lives on in the mainstream, as the ancestry of popular music in the twenty-first century. Black jazz artists changed the face of music as we know it, and at this time of celebration of black achievement, this seems crucial to acknowledge.