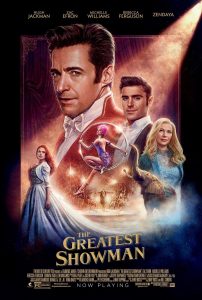

The Greatest Showman is the La La Land of 2018. It’s a feel-good, rags-to-riches musical that everyone can get behind. The stellar cast, up-beat soundtrack and heart-warming plot are bound to leave you skipping out of the cinema. What is there not to love about the story of a man who sees the good in everyone? It turns out, there is quite a lot to dislike. These features act as a smoke-screen to disguise how the film misrepresents the treatment of disabled and disfigured from the past.

In the film, we are introduced to P. T. Barnum; the creator of the ‘circus’ as we know it today. He is depicted throughout the film as a hero – a humanitarian, egalitarian entrepreneur who gives a platform to talented, beautiful people shunned by society. Barnum’s paternalism seems to be limitless. He accepts anyone and everyone into his care, while those he looks after adore him.

Yet this heart-warming figure is not the real Barnum. Far from it, in fact. Barnum was actually a racist con-artist who made his money by exploiting vulnerable people in society. As the creator of the ‘freak show’, his rags-to-riches story was built upon prejudice. The case of Joice Heath can exemplify this point. Barnum bought Joice, a blind and partially paralysed slave, and showcased her Thomas Jefferson’s 161-year-old slave. Without Joice’s consent, Barnum made $1500 per week from her suffering.

Unsurprisingly, the case of Joice Heath does not feature in The Greatest Showman. It would be too hard to put a Hollywood-spin on her tale. Moreover, while the film’s characters do allude to the real members of Barnum’s crew, it shouldn’t come as a shock that their exploitation is airbrushed out. Take the example of the ‘Little General’ (whose real name is not divulged). According to the film, he leaves his family aged 22 after Barnum asks him to join him as an opportunity for self-improvement. In reality, desperate parents sold their 4-year-old boy to Barnum, leaving the child with no control over a situation he did not consent to. Similarly, remember the ‘bearded lady’ with the beautiful voice? (again, what was her real name?). She was recruited to Barnum’s freak show as a 9-month old baby. This should demonstrate that The Greatest Showman spins an uplifting tale that is frankly false.

To rub salt in the wound of misrepresentation, the actors who play Barnum’s ‘oddities’ do not have the conditions that they are projecting. Keala Settle, who plays ‘the bearded lady’, does not have Hirsutism. The old woman who hands Barnum an apple at the film’s beginning does not have a facial disfigurement: it is added on with prosthetics. Of course, some rare conditions would be hard to cast. But others? Not so much. In a musical supposedly promoting the talents of those discredited in society, it is inherently contradictory that it can’t reflect this in its own casting.

The film’s cheesy reunion provides a happy ending, but I am left uneasy. The people Barnum supposedly cared for were used only to assist his social climbing. He travels the world and makes millions, while those he relied on are left behind when he no longer needs them. Upon leaving the cinema, I can only recall the names of P. T. Barnum and Philip Carlyle. The Greatest Showman perpetuates the marginalised depiction of the disabled that the film is supposedly fighting against. Yet again, Hollywood presents the struggles of the ‘other’ through the lens of a white, privileged male.

You can’t knock The Greatest Showman completely. The songs and dance numbers are catchy and even uplifting. You will probably be humming ‘This Is Me’ for weeks. Ultimately, the film is trying to teach its audience a moral lesson of acceptance and love. Whilst this message is important, you cannot re-write the past to convey it. P. T. Barnum was not the selfless, philanthropic hero that this musical suggests. The Greatest Showman is a romanticised yet false account of minorities in the nineteenth century.