Many literary tropes have their roots in the Bible

Asking whether the Bible influenced literature is like asking whether Bleak House is a long novel. But do we fully grasp the pervasive effect that the Bible has had on Western literary progression across the centuries? Too often the Bible is ignored for its commanding tone and antiquated ideas. I hope to show how pervasive and how important the Bible has been in influencing Western literature.

Hell. That infernal home of the damned has remained one of the most fearsome literary symbols for centuries. Since Dante’s epic imagining of the hellish journey in The Divine Comedy, Hell itself has remained a very real concept in the literary world. Shakespeare’s gothic drama Macbeth, for instance, incorporates both an inner and outer notion of the Hell symbol. Macbeth internalises his sin of regicide, he absorbs the fear of being damned to create a mental Hell within himself:

‘I am cabined, cribbed, confined, bound in / To saucy doubts and fears’ (3:4)

Shakespeare is able to mould the biblical notion of Hell into a psychological representation of inner conflict. Just so, Milton’s Satan in Paradise Lost, in a pivotal moment of self-doubt when he first views the Garden of Eden, feels his sin – his Hell – bound within his very being:

‘Which way I fly is Hell; myself am Hell’ (4:75)

But Milton’s Hell is far from conventional. It is not the Virgilian or Dantean depiction of a netherworld of punishment. It is, from Satan’s position, a malleable rendezvous point from which to renew their conquest against heaven. Unlike in Macbeth or T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland – or even in Beowulf – Hell is not just a bottomless pit of iniquity in Paradise Lost. Hell takes on revolutionary bounds; we experience Satan’s defiant conquest against (seemingly) belligerent supernal forces.

As Hell has been employed by Shakespeare and Milton to represent internal turbulence and darkness, so Heaven has become symbolic of purity and virtue in literature. The Dantean Ptolemaic treatment of Heaven, and how it is wittily satirised by poets such as Donne in The Sunne Rising, is the traditional image of Heaven. However, much modern literature instead concentrates on the connotations of heavenly purity, rather than heaven itself.

Consider the anti-heroic Gatsby. Whilst corrupt, Fitzgerald weaves into Gatsby’s character – particularly upon his death – something pure and Christ-like; the incorruptibility of his dream:

“So he waited, listening for a moment longer to the tuning-fork that had been struck upon a star. Then he kissed her. At his lips’ touch she blossomed for him like a flower and the incarnation was complete.”

Or the heavenly bounds with which Lawrence, in his highly poetic prose, attains in The Rainbow. Whether it be the fierce collision between light and dark in the courtship of Tom and Lydia, or the rhythmic interaction between Will and Anna Brangwen under the cast of moonlight, The Rainbow incorporates fundamental biblical notions of heavenly light and satanic darkness. Therefore, although unconventional, the biblical treatment of their characters enables Lawrence and Fitzgerald to draw on something universal, something biblical, something ingrained within Western culture.

If we look back a few centuries, Edmund Spenser allegorises essential biblical themes in The Fairie Queene in a similar manner. The Fairie Queene was intended to justify the one true faith of the Anglican Church, embodied in the pure Una, and condemn the duplicitous Catholic Church, represented by the manipulative Duessa. The Christ-like purity of Gatsby and the connotations of virginal purity in the light of The Rainbow are consonant with the depiction of Una and, much more important for Spenser’s reputation, the fleeting appearances of Queen Elizabeth herself throughout the epic text, with whom he hoped to curry favour.

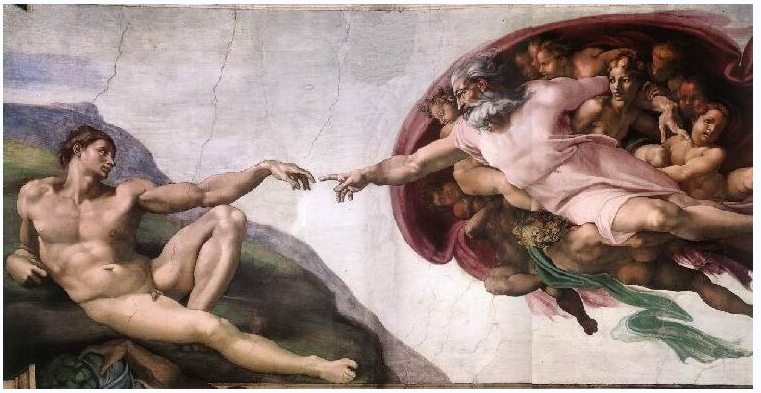

Christian wonder and fear at images of Heaven and Hell have inspired a plethora of literary interpretations. Whether drawing from ingrained images of purity and corruption in more modern works or actually dramatizing the Christian journey, the biblical impact is difficult to quantify. Nevertheless, perhaps the most central subject that lies at the heart of human existence and literature inspired by the Bible is creation. The origin of the universe, of our world and of humanity lies at the heart of all existential questioning; and the literature for this spans as wide as the question itself.

Völuspá, an Old Icelandic text likely written during the Christian conversion period of the late 11th century in Iceland, is founded upon this idea of creation. It displays a collision between Christian and pagan ideas. Dealing with the creation, fall and recreation of the universe, Völuspá depicts the lives of the heathen gods in their distinctly human fallibility. And yet the poet seems to recreate the universe just as Iceland was being recreated at the time: under a Christian god with Christian ideals.

By contrast, Milton’s Paradise Lost was intended as a theodicy rather than a depiction of creation like Völuspá, ‘to justify the ways of God to man’. However, God’s defence of himself in Book 3 rings with hollowness. His actions incite a disaffected, fallen Adam to question him in a manner that calls to the heart of human fears and existential reasoning. Just as Shelley’s monster in Frankenstein demands reason for his existence, so Adam challenges his creator:

‘Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay

To mould me man? Did I solicit thee

From darkness to promote me?’ (Bk X:743–5)

And in just the same light, Frankenstein’s monster, who has been influenced by these words of Milton’s Adam, speaks of the misery of his existence:

‘Cursed, cursed creator? Why did I live? Why in that instant, did I not extinguish the spark of life you so wantonly bestowed?’

The question of existence penetrates to an intimate kernel of the human condition. Both Shelley and Milton envisage disaffected creations, embittered by existence. Why should we be defined by a creator? Why should any higher being – heavenly or human – have the power to bestow life? Their voices resonate with all humanity, their thoughts aided by biblical precedent.

I feel too often in our secular society we resist any respect of the Bible; we feel, perhaps, that true human meaning has been too often obscured by austere doctrine. The Bible is an essential foundation in Western literature. Epic dramatizations of it’s meaning, in The Divine Comedy and The Fairie Queene are wonders for the literary critic. But for texts to be able to harness fundamental biblical themes to enhance meaning in a more implicit manner, and deal with fundamental human issues, I think is incredible. The Bible has affected texts in both dramatic and subtle ways; to appreciate the scope of this influence in both its grand and inconspicuous forms is to appreciate the very building blocks of Western literature itself.