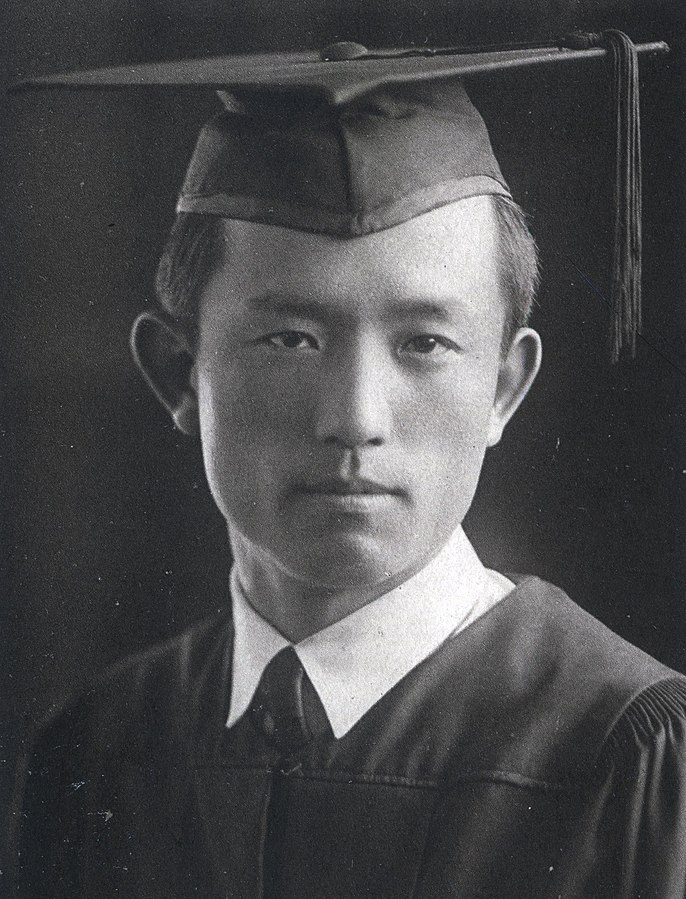

Photo of Yun Dongju when he graduated from Yonhi College, which is present-day Yonsei University. Unknown author on Wikimedia Commons with license.

*Light spoilers of the Netflix series Squid Game included in the introduction of this article*

It has already been several weeks since the South Korean thriller series Squid Game has topped the charts on Netflix. The series is not only incredibly captivating but is also a story that let thousands of non-Koreans explore the niche-est corners of Korean culture, from the scrumptious honey cookie Dalgona to the nerve-racking game of ‘Red Light, Green Light’ ( I promise as a South Korean myself that the actual game does NOT bring about the kind of calamity shown in the series. Trust me when I say that I’ve never shed a single drop of blood while playing that game countless times in my childhood. ) . Listening to housemates and strangers chat about the show made me feel grateful that Korean culture was gaining so much positive attention, but the spotlight cast on Korean food and children’s games reminded me of a part of the culture that was rather hidden from that beam of fame: Korean literature. Now that autumn has officially started and winter is approaching, I thought I might introduce you to some beautiful Korean poetry that are set in those two seasons. Who knows, if these poems were featured in Gi-hun’s literature textbook when he was still a little schoolboy?

*All three poems below can be found on Wikimedia Commons and were translated into English by myself.

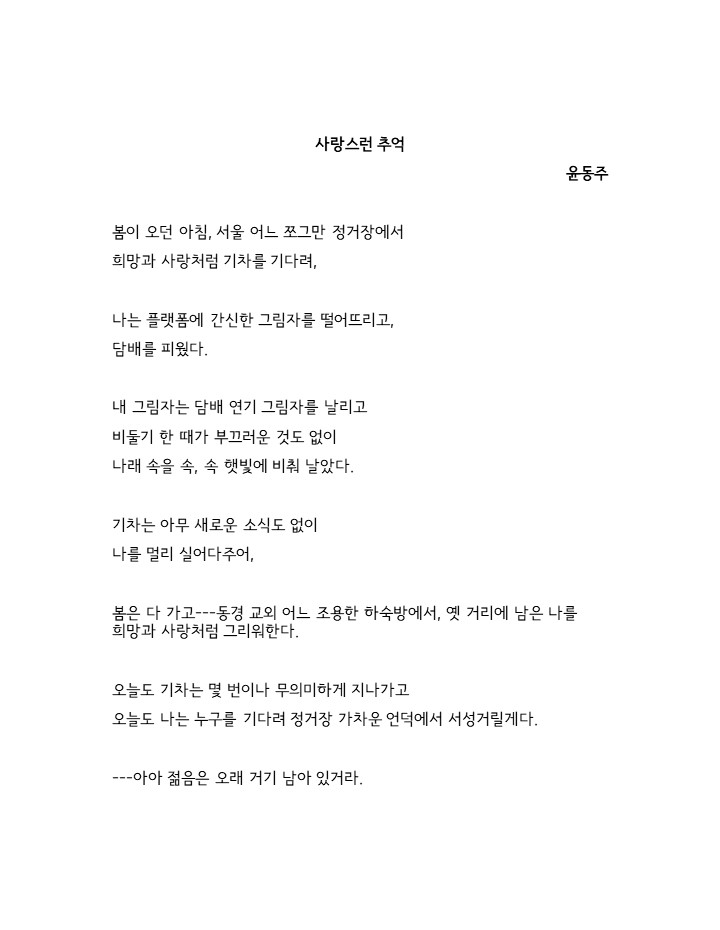

1) ‘A Lovely Memory ( 사랑스런 추억 )’ by Yun Dongju ( 윤동주 )

Original text:

Image: typed by myself on Microsoft PowerPoint; text in the image is retrieved from Wikimedia Commons with license.

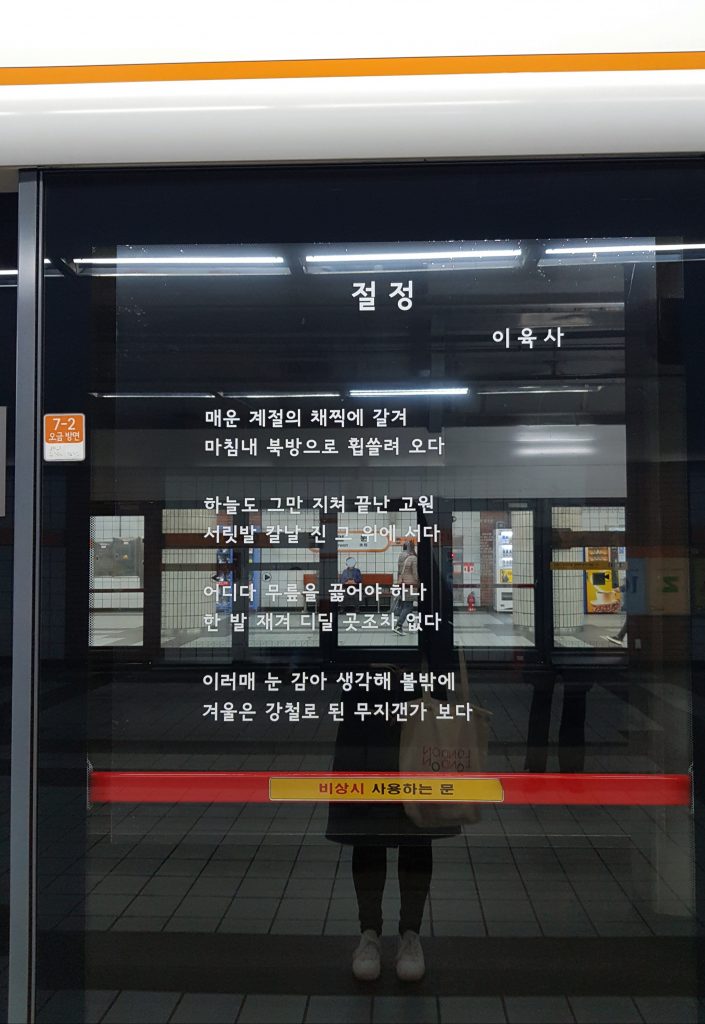

Translation:

Image: typed by myself on Microsoft PowerPoint; text in the image is a translation of the original text from Wikimedia Commons with license.

This poem is not exactly set in the winter, but rather, on the brink of spring. However, if you imagine yourself standing on a chilly, deserted platform with the speaker, you would still be able to smell the lingering echo of hail and snowflakes. In this poem, the speaker lights a smoke as he ( Yun’s poetic speakers are often interpreted as the poet himself ) waits for his train and reminisces about his past self.

Personally, the last line of the poem is particularly striking— it is written in simple words, but ironically, that is exactly what gives it so much gravity, almost making it feel like a declaration. It feels like the speaker is finally uttering out what he had longed to say in the previous 13 lines of the poem, something honest and simple even his pretty words and skilful imagery had failed to demonstrate. Were all of his random digression, from the image of his smoke to the pigeons flapping their wings, merely his futile effort to distract himself? Was the speaker actually waiting for the train or did he have something else in mind? To me, the last line doesn’t read like a closure but rather as an introduction, like the engine of a locomotive that is more than ready to carry the speaker to the place he is bound to be.

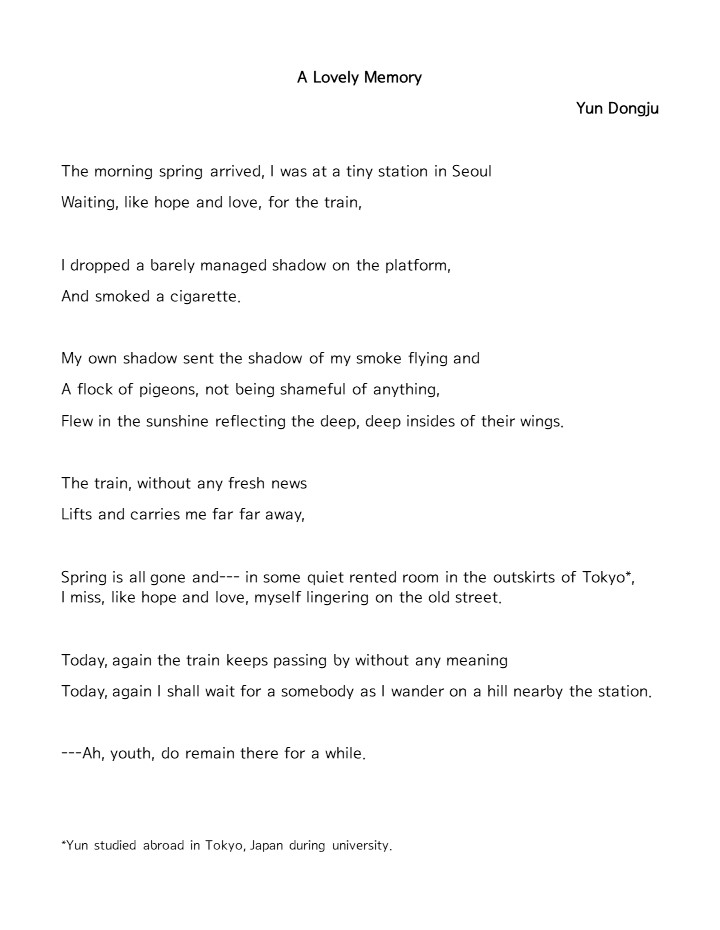

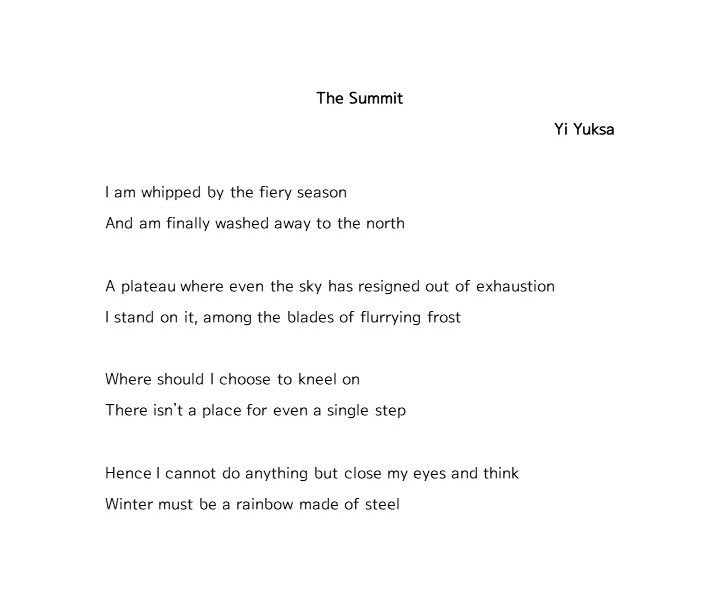

2) ‘The Summit ( 절정 )’ by Yi Yuksa ( 이육사 )

Original text:

( This poem was displayed at a subway station in Seoul. Seoul’s subway stations are known for featuring poems written by poets and even citizen contributors (!) on their screen doors. )

Image: taken by myself; text in the image can be found on Wikimedia Commons with license.

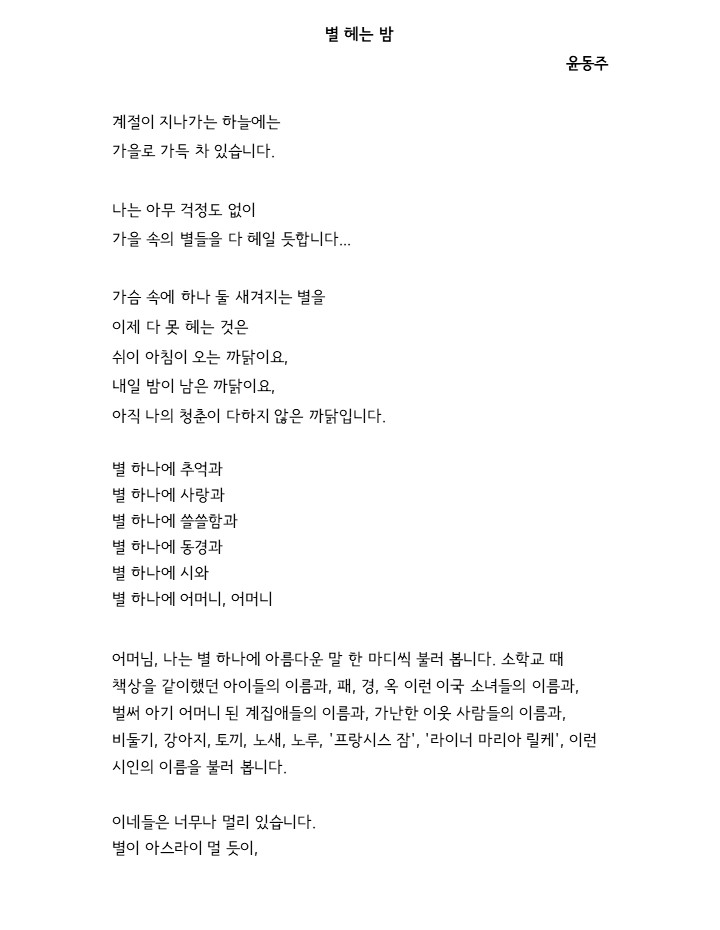

Translation:

Image: typed by myself on Microsoft PowerPoint; text in the image is a translation of the original text from Wikimedia Commons with license.

This poem is written by Yi Yuksa, a poet who fought for independence when Korea was colonised by Japan from 1910 to 1945. Yi Yuksa was actually his pen name, and it is known among the general public that the name comes from his prisoner number 264 ( read as ‘yi yuk sa’ ( two six four ) in Korean ) when he was imprisoned in Daegu for trying to stand up against Japanese rule.

As he was so determined in liberating Korea, many of his poems are famous for having a political undertone. ‘The Summit’ is also one of them— the image of winter in the poem is known to symbolise the excruciating metaphorical winter Koreans had to face during the 35-year colonisation. With little girls and women taken to sexual harassment camps and their family members being forced to speak and change their names to Japanese, the prolonged barren season Korean people had to face would have been even more severe and colder than actual winter.

I also greatly admire the last line of this poem, ‘Winter must be a rainbow made of steel’. Please feel free to put yourself in Yun Dongju’s shoes once again and linger on this line ‘for a while’.

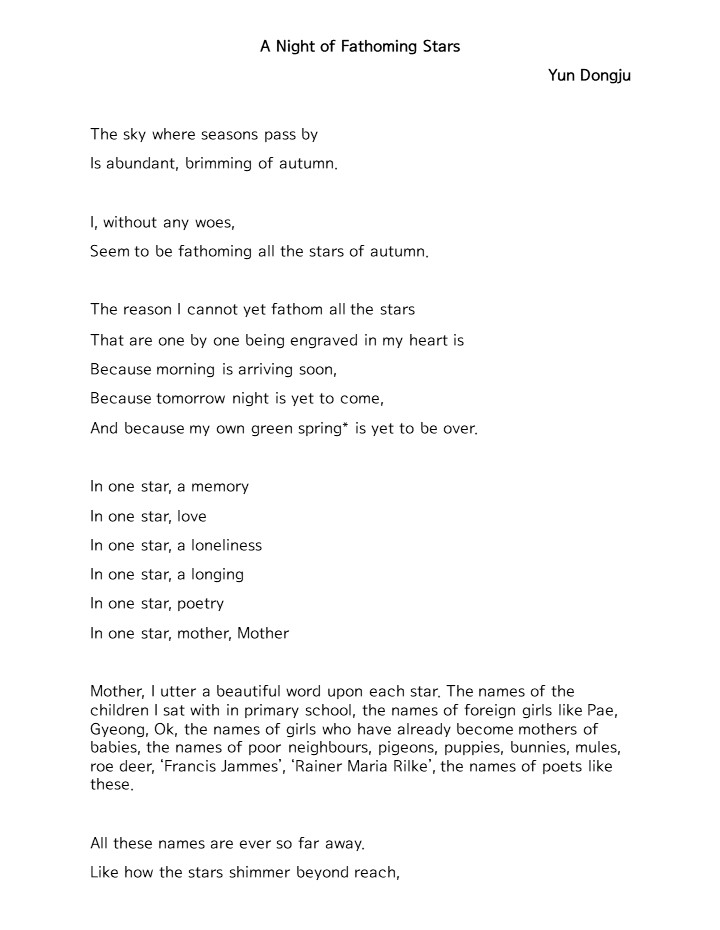

3) ‘A Night of Fathoming Stars ( 별 헤는 밤 )’ by Yun Dongju ( 윤동주 )

Original text:

Image: typed by myself on Microsoft PowerPoint; text in the image is retrieved from Wikimedia Commons with license.

Image: typed by myself on Microsoft PowerPoint; text in the image is retrieved from Wikimedia Commons with license.

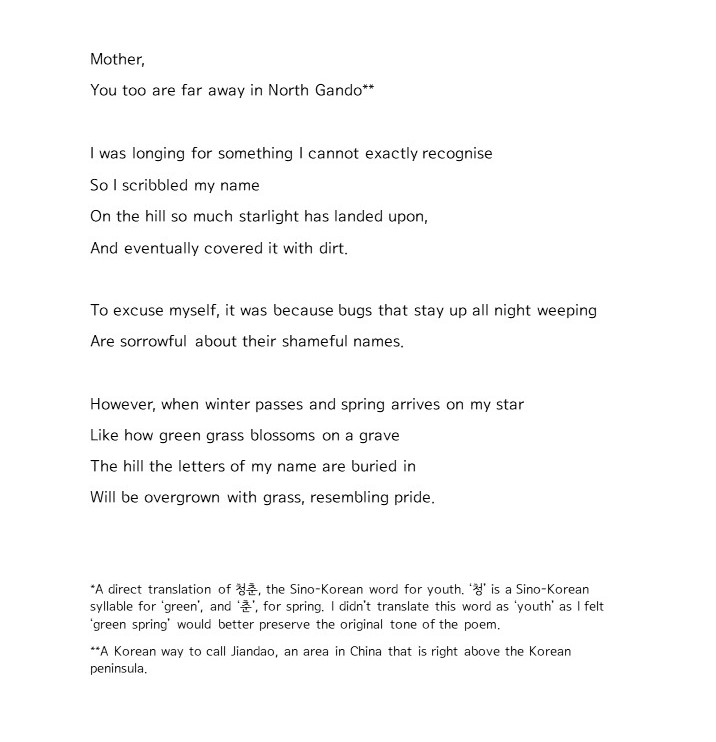

Translation:

Image: typed by myself on Microsoft PowerPoint; text in the image is a translation of the original text from Wikimedia Commons with license.

Image: typed by myself on Microsoft PowerPoint; text in the image is a translation of the original text from Wikimedia Commons with license.

It’s Yun Dongju again! I really felt the need to finish the article with this poem because I can confidently say that this is one of the most famous Korean poems of all time, if not the most. Literally anyone in the streets of Korea would have heard of this poem at least once in their life; it’s taught in almost every single school in South Korea and is undeniably one of Yun’s most notable works.

In the poem, the speaker ( who is also interpreted as Yun ) watches the stars in an autumn sky. Counting the stars, he bestows a certain meaning on each of the stars and reminisces about the schoolmates, neighbours, and poets he used to know. Lastly, he pictures his mother in the night sky. This poem is quite lengthy compared to the other two poems, but I chose to include the full text to let you get the full experience of the lyrical, confessional language of 23-year-old Yun.

4) And for those of you who stayed until the end of this journey…

I have a bonus recommendation for you! It’s the film Dongju: The Portrait of a Poet. You might have already guessed from the title, but it is a biographical film of Yun Dongju. It is about his indestructible passion for literature and the struggles he went through being a prominent figure of Korean resistance during Japanese colonisation. The film does have some fictional elements, but I still thought it was an excellent portrayal of how Yun was as a person. Also, there is a scene in the film where the actor who plays Yun recites ‘A Night of Fathoming Stars’ to himself, lying down on his prison bed.

Well then, hope you enjoyed my brief tour of Korean poetry! Genuinely, picking out which ones to write about was a moment of blissful pain for me— I had to weed out a dozen equally beautiful poems just to fit the word count & not infringe upon any copyright laws. I may or may not be coming back with a similar tour but until then, please do savour the beautiful autumn in Durham and find your very own ‘green spring’ in it!

Featured image: Unknown author on Wikimedia Commons with license.