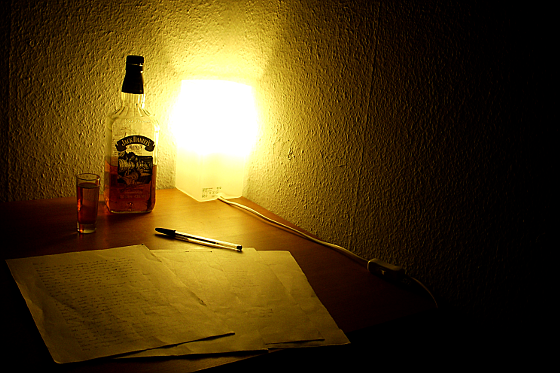

Does alcohol help the writing process or even improve the result?

In The Trip to Echo Spring: Why Writers Drink, author Olivia Laing traces the literary genealogy as determined by alcohol and finds a tangled web among many famous American (male) writers. The habit of drink united Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald in Paris, made Raymond Carver and John Cheever commiserate less about being stuck in Iowa, and undoubtedly provided connections to many others. If we are not strictly concerned with direct interactions or gender segregation between writers, then alcohol brought together an indiscriminate cohort including Patricia Highsmith, Truman Capote, Edgar Allan Poe, and Grace Metalious. Laing uses Echo Spring to express “[her] faith in literature, and its power to map the more difficult regions of the human experience and knowledge,” unlike previous enquiries which treated alcoholism and writers as a shameful phenomenon. In addition, this endeavour is intensely intimate to Laing, having come from an alcoholic family. (She admits that this very reason is why she chooses not to focus overly much on women writers.)

Laing’s narrative follows her own journey to the titular Echo Spring, as well as the lives of well-known writer alcoholics Tennessee Williams, Fitzgerald, and others. Throughout the story, she continues to explore these men’s dependence on drink and its subsequent influence on their famous works. What emerges then, remains the strong influence of booze on works like Tennessee Williams’ A Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, where the phrase “Echo Spring” comes from (“I’ll drink until I get it.”) For another famous utterance, I could point to the often misattributed famous mantra, “Write drunk, edit sober.” However, Ernest Hemingway never actually said this, nor did he follow his own alleged advice; in many ways, his true sentiments regarding drinking were much more complex. After the death of F. Scott Fitzgerald, he wrote the following in a letter to Arthur Mizener, one of Fitzgerald’s first biographers: “alcohol, that we use as the Giant Killer, and that I could not have lived without many times; or at least would have cared to live without; was a straight poison to [Fitzgerald] instead of a food”.

While alcohol certainly played an important role in landscaping the American modernist scene, it probably is important as well, to examine the effect on contemporary writers today, ourselves among them. The connection between writers and the alleged “bottle” has endured, even if we are no longer relying exclusively upon inebriation to produce literary epics. Drinking to establish a sense of solidarity has, in some ways, fallen out of fashion, or perhaps we no longer like to think about the possibility. Calling upon alcohol to stave off anxiety and open up certain channels of inspiration are now popular reasons why we drink as writers; at least, this is the consensus I’ve reached via personal experience and a (very) informal poll. As a result of various conversations with my British friends and Google however, it would seem that alcohol doesn’t hold the same sort of mysticism for British writers as it does for their American counterparts. One friend speculated that American writers tend to drink because they didn’t feel confident enough to write sober; I agreed, only for him to point out that I probably hadn’t written that down because I hadn’t yet had a drink.

To additionally attempt to parse out some of this mysticism, I’d like to examine in depth the reasoning behind Hemingway’s statement to Mizener. He all but admits here that although he sees inebriation as a helpful tool that personally helps him confront challenges in his writing, that such an approach may not be appropriate for everyone. Unlike “Write drunk, edit sober,” Hemingway’s real views on alcohol are more nuanced, and the habit itself is not exactly a one-trick pony.

Though in fact, it is partly true that Laing’s book works because it simultaneously invokes and dispels the myth that Americans have built up around alcohol. After all, with America’s rather sordid history with prohibition and obsession with finding what Jack Kerouac terms “it”, alcohol has become in some ways continued as an exclusive activity rather than an inclusive one, as it seems to be in the English context. My argument fails slightly if I account for Dylan Thomas being Welsh, although he did spend his last days in New York City. Although “it” is a decidedly vague term, it has its uses. As “it” is explained in On the Road, Kerouac’s quasi-autobiographical Beat Generation manifesto, it appears to be some sort of a “perfect high” – an ideal state –- that remains unattainable, even during the most intense state of inebriation. In chasing “it,” the two protagonists of On the Road, the aptly named narrator Sal Paradise, and his friend Dean Moriarty open themselves to various forms of intoxication, including drugs. It is Dean, not Sal, who briefly gets to experience “it” at a jazz concert. Still, despite Kerouac’s best efforts to shed light on “it,” the feeling essentially is changeable from person to person, and as such, perhaps the feeling can never truly be.

I find it slightly odd that Laing neglects to mention Kerouac in Echo Spring, for it is Kerouac who attempts to put into words what “it” means in order to further understand the concept. However, it is also plausible to surmise that she wanted to keep neatly to the theme of writers who drink, rather than writers who are prone to drug use. Either way, Kerouac proves vital in making sense of “it,” and consequently is valuable in a discussion regarding writing and alcohol.

Undoubtedly, what we drink (or don’t drink, for that matter) will always probably affect the way we view its relationship with literature as a whole. Whatever your preferences, I would like to end with a resounding recommendation for Laing’s The Trip to Echo Spring: Why Writers Drink; despite the caveat that it mostly likely could have benefited from being called Why (American) Writers Drink, it still opens a non-judgemental way to view a practice that has long shaped the literary tradition.