When we think of the word journey, what often comes to mind is sailing across the sea, lifting off from the ground in an airplane or the shrill whistle of a railway coach as it pulls away from the station. But there are all kinds of journeys that don’t require the assistance of external transport. In the 19th century, Charles Baudelaire popularised the idea of a flâneur—a self-transporter and street wanderer— who ambles leisurely amidst the thronging crowds in urban spaces. The flâneur is at once an involved member and a distant spectator, absorbing the sights, sounds and smells of cityscapes, acutely aware of the changing psyches of himself and those around him.

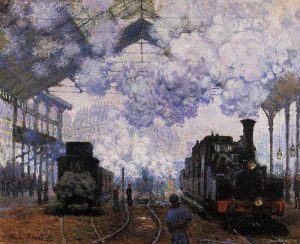

Monet’s images of the railway highlighted the mobility of the male flaneur in Paris. Image source: Flickr

Thinkers and writers after Baudelaire have different conceptions of the flâneur, his role, and how he performs it. For instance, in Walter Benjamin’s seminal work The Arcades Project, the flâneur is a walking anachronism, yearning for a time long gone. Much like a photograph, the flâneur beholds the city in retrospect, “reverting to the memory of the city”, a flânerie tinged with nostalgia. Writer Edgar Allen Poe interprets the flâneur as a man terrified of solitude, thus seeking a crowd in his story The Man of the Crowd. The unnamed narrator follows an ‘idiosyncratic figure’ all around the streets of London, hoping to discover his identity and intentions, but failing miserably. Finally, in despair the narrator concludes “er lasst sich nicht lesen”—it (here, flânerie) does not permit itself to be read.

Psychogeography, pioneered by Guy Debord, is the study of how external environs and habitats influence thinking and behaviour patterns. Among its many tenets lies the demise of the separation between art and its surroundings. One example in recent literature that explores this idea that architecture, urban planning and multitudes (among other factors) colours one’s perceptions, are Julius’ solipsistic meditations in Teju Cole’s 2011 novel Open City.

Until the 20th century, flânerie was a man’s domain, women had neither the authority nor the agency to go on long, unaccompanied walks. A flâneur could slip in and out of the cracks of invisibility. In contrast, a female wanderer or a flâneuse, a novelty in the streets, would draw too much attention to herself. She would become the observed rather than the observer. But these constraints were soon defied by figures like Lauren Elkin, who in her book Flâneuse: Women Walk the City (2016), wrote:

“The joy of walking in the city belongs to men and women alike. To suggest that there couldn’t be a female version of the flâneur is to limit the ways women have interacted with the city to the ways men have interacted with the city…Perhaps the answer is not to attempt to make a woman fit a masculine concept, but to redefine the concept itself.”

In contrast, Morisot, a female impressionist, showed the contained lives of middle class women in the age of the Flaneur. Image source: Flickr

Elkin traces the lives of several women (and her own) who altered the course of literary and political history simply because they decided to walk—from writers Virginia Woolf and Jean Rhys, to journalist Martha Gellhorn to the character Cléo in Agnès Varda’s 1962 film Cléo from 5 to 7. Elkin argues that for women, walking is essentially a transgressive act:

“She voyages out and goes where she’s not supposed to; she forces us to confront the ways in which words like ‘home’ and ‘belonging‘ are used against women. She is a determined, resourceful individual keenly attuned to the creative potential of the city and the liberating possibilities of a good walk.”

It is interesting to note how modern technology transforms the walking experience; one can palpably note the difference between walking with earphones plugged in and without. Music sometimes affords the unique probability of a journey within a journey, with the song transposing the experience of walking and vice versa. Moreover, devices like the Fitbit can distract the walker, who might then be preoccupied with achieving a target, thus disregarding his/her surroundings.

For many artists and creators, the several ingredients of the great soup that is the city pique and satisfy their fantasies. Perhaps you are the starved artist, or an old soul who is straining to capture the fading notes of a once-melodious city. You might just be someone who wants to indulge in an exercise of peripatetics for the sheer joy of it. But the important thing is, you are walking. You are seeing, and feeling, and living. As Elkin says, “Slow down: it’s the only way to guarantee your immortality.”