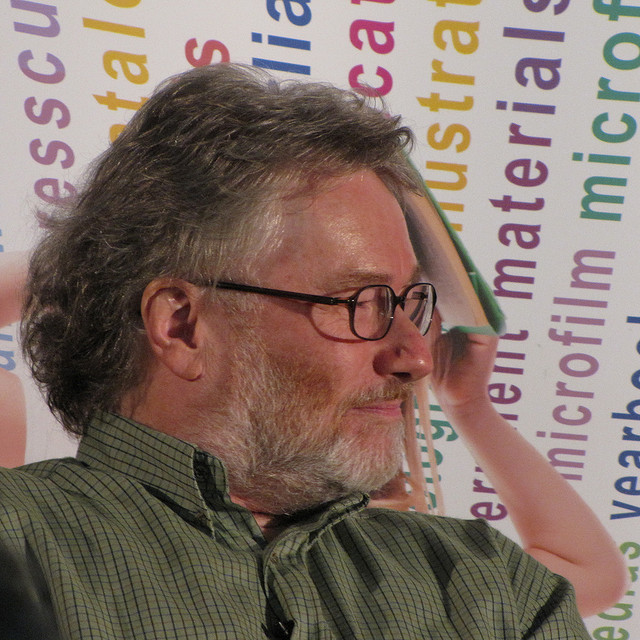

The writer in interview at the Edinburgh Central Library

2013 saw the death of many remarkable literary figures, but for me Iain Banks was the one for whom I was most deeply affected by, not least because of the young age at which he passed away. He died aged fifty-nine on 9th June 2013, two months after he announced that he had terminal gall bladder cancer in April 2013.

Banks was born in Dunfermline, Fife, on 16th February 1954, the only child of an admiralty officer and a former professional ice skater. As a young boy, he lived first in North Queensferry and later in Gourock, Inverclyde, moving because of his father’s naval commitments. He was educated at Gourock and Greenock high schools before attending the University of Stirling, where he read English, philosophy and psychology. After graduating in 1975 he took a series of jobs, including working as technician at the Nigg Bay oil platform construction site and at the IBM computer plant at Greenock. He then worked as a clerk in a Chancery Lane law firm in London. Here he met his first wife, Annie; their split, after fifteen years of marriage, was widely publicised, and he went on to marry his partner Adele after announcing his illness.

Whilst he worked during these early years, he was writing, and by the late 1970s he had three books written, until finally his first published novel, The Wasp Factory, was published in 1984, when he was 30 years old, though it had been rejected by six publishers before being accepted by Macmillan. Editor Richard Evans said that he was proud they had found it on the unsolicited manuscript pile and saved it from yet another rejection – and I’m sure all of Banks’ fans agree. The plot twist at the end of the novel has come to be one of the greatest in modern fiction. It was followed by Walking on Glass in 1985; the multiple narrations featured here became a key element in many of Banks’ later books. His next novel The Bridge, published in 1986, featured three separate stories told in different styles, and it remained the author’s own avowed favourite throughout his life. Two of his other books also deserve a special mention. The Crow Road, published in 1992, which is very mindful of Banks’ Scottish roots, and Complicity, which appeared a year later, have both been praised as two of his greatest achievements.

An expert on Scotch whisky, he published Raw Spirit: In Search of the Perfect Dram in 2003, an account of his travels through Scotland in search of the history of malt whisky. This expertise served him well on Celebrity Mastermind when he won with his specialist subject of Scottish whiskies and distilleries. However, he later admitted at dinner parties that he’d ended up losing a taste for it due to this overindulgence. Fortunately for his readers, he never lost a taste for writing, publishing 26 novels in his lifetime. Had it not been cut short, I’m sure there would have been many more to come.

The line between science fiction, fantasy and mainstream literature was initially blurred by Iain Bank’s contributions to the literary world – eventually he made deeper distinctions by becoming Iain M. Banks for his science fiction work, the ‘M’ standing for Menzies, his parents’ intended original middle name for him. The first stolidly science fiction novel he wrote was Consider Phlebas, published in 1987, which bears the first introduction to The Culture, a galaxy-hopping society run by authoritative but munificent machines – it would feature in most of his subsequent science fiction books. The Player of Games, published in 1988, was followed by Use of Weapons, 1990, but despite the difference in genre, his style and narrative trickery continued throughout, much to the delight of his readers. His most recent sci-fi novel, The Hydrogen Sonata, was released in 2012. Banks was animated by political causes with his left-wing beliefs and a well-voiced critic of Tony Blair during the war in Iraq – many of his views have been said to have been aired within his writing, notably in his science fiction Culture Series, whose characters’ mission it is to spread democracy, secularism and social justice throughout the universe.

Banks asked his publishers to bring forward the release of his final book, The Quarry, so that he could see it on the shelves – sadly the release date of 20th June was too late for him, but he was presented with copies three weeks before his death, according to publisher Little, Brown. This book describes the final weeks of the life of a man with terminal cancer. Banks said he was some 87,000 words into writing the book when he himself was diagnosed: “I had no inkling. So it wasn’t as though this is a response to the disease or anything, the book had been kind of ready to go,” he told the BBC.

He achieved great success in his life, with critics and readers alike flocking to praise him for his masterful way with words. From early on he achieved accolades such as the honour of being one of Granta’s Best Young British Novelists in 1993, aged then 39. The Wasp Factory was ranked as one of the best 100 books of the 20th Century in a 1997 poll conducted by book chain Waterstones and Channel 4, and in 2008 he was named one of the 50 greatest British writers since 1945 in a list compiled by The Times.

The writer was particularly well-loved by his fans, not least because he was consistently open and honest with them throughout his career. He often communicated with them via the internet, and let the media into his life in a way which most writers avoid at all costs, through fairly frequent interviews. Many of his fans had the pleasure of meeting him, usually after interviews or public readings. This closeness with his fans which he relished so, made him vividly aware of what his readers thought of his books; he was very astute with regards to this, and it made him a better writer all the more for it. This remained the case even when he was diagnosed with cancer – forming a website called Banksophilia, he gave family, friends and fans alike a platform to leave messages of sympathy for him, as well as his own space to announce and air thoughts on his illness.

The tributes that poured in after his death demonstrated just how valuable he was to people. Fellow writer Iain Rankin highlighted one of his most endearing qualities as a writer, in that “You never knew what you were going to get, every book was different” – it was simply impossible to be bored with his writing. Ken Macleod, meanwhile, emphasised his skill further by asserting that “He brought a wonderful combination of the dark and the light side of life and he explored them both without flinching”. He received homage from not only writers but politicians, with Scotland’s First Minister Alex Salmond stating: “Iain was an incredibly talented writer whose work, across all genres, has brought pleasure to readers for over 30 years.”

It is undisputable that for his fans, his memory lives on in his words. Neil Gaiman ended his own tribute to Iain Banks with this: “If you’ve never read any of his books, read one of his books. Then read another. Even the bad ones were good, and the good ones were astonishing.” You know what? I couldn’t have put it better myself.