What do we think of authors who step into the shoes of another, taking up their characters and plot lines?

For Christmas my cousin received a series set of Enid Blyton books. My sister and I flicked through them, nostalgic as we compared the updated covers since we last read them. And then my cousin noticed something it had taken my sister over a decade to observe. Six of the books were written by Enid Blyton, while the other six were later additions by an author called Pamela Coz. With the same cover illustrations and branding, it was difficult to tell the difference, and my sister’s surprise proves there was little to distinguish the writing style of the books themselves.

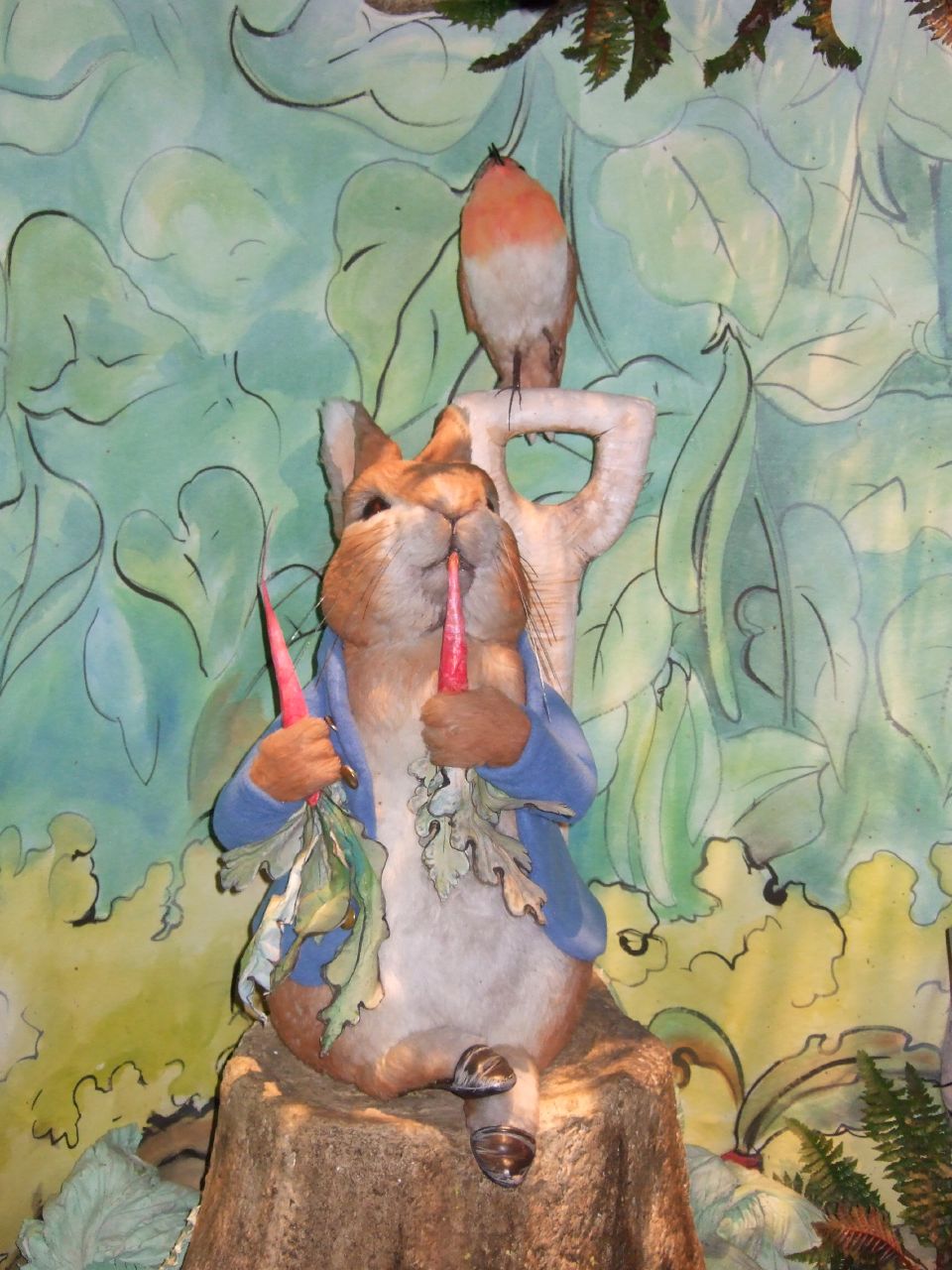

Cynics might argue that this is a publishing money-spinner, playing on the appeal of a certain character or series. Certainly, there is a market for these books, and avid fans will seek out anything they can related to their chosen franchise – think J.K. Rowling’s Tales of Beedle the Bard. Indeed, the initiative for Emma Thompson’s recent sequel to Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit came from her publishing company. Frederick Warne, an imprint of the Penguin Group, sent Thompson a letter purporting to be from Peter Rabbit, along with a radish leaf, inviting her to write about his further adventures.

However, Emma Thompson’s reaction to this invitation seems to show a less materialistic attitude to the franchise of books. She told The Telegraph that “If Frederick Warne had sent some official letter I would have said don’t be ridiculous, I can’t think of anything I want to do less than step into the footsteps of a genius like Potter.” Instead, she was won over by the endearing invitation purporting to be from a well loved character rather than a simple money making initiative.

Peter Rabbit: loved well enough to last.

Another author who admits to being drawn to the untold stories of a classic character is Charlie Higson, author of the Young Bond series. In his introduction to ‘Danger Society: Young Bond Dossier’, Charlie Higson cites a fictional obituary giving scant information about Bond’s parentage and childhood which inspired him to embellish five novels about James Bond’s years at Eton. Higson describes the process of depicting the transformation from the ‘normal schoolboy’ James to the ‘fairly cold-blooded killer’, Bond, as ‘exciting’. However, he does raise the question of whether Bond creator Ian Fleming would have approved of his prequel novels, saying ‘I don’t for one moment think this was the childhood he imagined for his hero. I expect he thought James would have a pretty normal life before the war broke out.’ However, Higson is writing for children. Literature aimed at this demographic, particularly books about boys aimed at boys, has expanded since Fleming’s time, with the likes of JK Rowling’s Harry Potter and Anthony Horowitz’s Alex Rider being similar examples of this trend. Therefore the rise of this genre perhaps provides new opportunities for writers to explore untold stories that had never before been considered.

What is more, many writers will argue that novels of this kind create much more about a character than is included in the original novel. This is evident by the number of sequels authors themselves create, or the way in which characters from one novel might have an almost cameo role in another – take Jacqueline Wilson for another example of children’s novels. If writers themselves create interconnecting worlds, then, in novels, as in life, there are only so many of these paths which can be explored.

Some additional novels, therefore, might embellish the tales of peripheral characters, or that of the protagonist at a different life stage – arguably a different character to the one portrayed in the original books. Yet other novels focus on the further adventures of the same character. Higson’s Young Bond was not the first addition to the story: after Fleming’s death, Bond novels were written by Kingsley Amis, John Pearson, and Christopher Wood, and then the series was later continued by John Gardner in the 1980s and then Raymond Benson in the late 1990s. Most recently, Sebastian Faulks, Jeffery Deaver and William Boyd have contributed to Bond’s story. However, different authors take different approaches; some updating Fleming’s series and time frame and others setting the novel within the original decade. The characterization of each Bond, too, is different.

The success and the coherence of the sequels, then, is arguably due to the strength of the character brand. Novels and films released almost simultaneously created a sense of character even in different situations. Moreover, the choice to have different actors playing the part of Bond further reinforces the strength of the character’s identity even across different characters, situations, and different media used to communicate them. A certain aspect of franchise-related income seems influential here, especially because in many cases it was Bond’s publishers which approached each author. However, this would not have been successful without the readers’ enthusiasm for the character. Clearly, a character’s revival depends on both the impetus of the publisher and the popularity of a much-loved character.

This, then, seems to be where the boundary lies between generating revenue and simply writing about a character for pure enjoyment. Of course writers and publishing houses aim to make a profit, and do so by assessing what is popular on the market. Yet while spin-off books may sell initially on the brand name alone, to remain popular they must embody the spirit of the initial character or book, whilst perhaps putting a new spin on it, introducing it to a new audience or exploring an untold story. Readers must be willing to buy and read sequels and additional books, and will do so avidly if these aspects are strong.