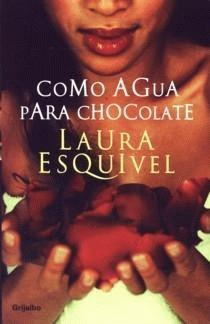

Like Water for Chocolate is one of the most famous magic realism books of all time

So, who is Laura Esquivel and why is she so special to me? Essentially Laura Esquivel, along with Isabel Allende, is one of the female forerunners of the post-boom literary movement in Latin America and, in my opinion, her novel Como Agua Para Chocolate is a modern classic that can easily contend with anything written in any language over the past hundred years. I’m aware that this is a daring statement but Como Agua Para Chocolate is a daring novel; encompassing five generations, centuries of female oppression and a revolution, as well as twelve recipes, in two hundred or so pages. After reading this novel I became convinced that Laura Esquivel was a literary genius on a par with Joyce or Dostoevsky. I still stand by this today and I want to share why.

The title (Like Water for Chocolate in English) is a reference that likens the protagonist Tita’s emotions to the boiling water used to make hot chocolate; all throughout the novel Tita is simmering with suppressed rage, desire and grief which eventually come brimming to the surface. Upon starting the novel the reader is quickly alive to the fact that Tita is oppressed not only by a tyrannical mother but by a family tradition which dictates that she must stay single to care for her mother until her death. Things go from bad to worse with the introduction of the character of Pedro – the man who proves to be the source of most of the drama in Tita’s life. Pedro and Tita are in love but marriage isn’t an option for them, so Pedro takes it upon himself to marry Tita’s elder sister Rosaura in order to be near her. This is where it becomes apparent that the title of the novel is a stroke of genius; Tita is unable to vocalise her intense grief over this situation so, in her imposed role as family chef, uses food as a way to express her feelings. You don’t quite get what I mean? This example might clear things up: when Tita is enlisted to make the wedding cake for her sister and Pedro’s wedding, all the guests who eat it are struck down by a mysterious sickness that makes them think of the lost loves of their life.

When first reading this, I was struck not just by its incredibly poignancy but its undeniable cleverness. Esquivel adapts the male dominated “bildungsroman” to suit her female protagonist: the pursuit of self-knowledge through wider world experience is off-limits to Tita- she must undergo her self-discovery in the only place available to her, the kitchen. It is through the different dishes that Tita creates and the new feelings and sensations they evoke that she can learn about herself as a person. This serves to show that the life concerned with family and the domestic is not the sole reserve of weak, shallow individuals. For Tita her life in the kitchen is equally, if not more, rewarding than the lives of the men around her. Furthermore, Esquivel parodies the crassest elements of the “folletín” (think Mills and Boon for Latin America) while at the same time utilising magical realism, the literary genre of choice for the authors belonging to the Latin American Boom. This serves to do two things, firstly to poke fun at the residual sexism that leads to the misconception that cheap romance novels are all that can be written by women. And secondly, to show that she, and the wealth of Post-Boom female authors, are capable of appropriating the techniques of their predecessors in order to give a voice to Latin American women in a way which the Latin American Boom, practically absent of female members, failed to do.

Another level on which Como Agua Para Chocolate is truly original is its awareness of and enthusiasm for the rest of the literary world. The novel is bursting with allusions to other works of literature; for example, when Tita’s emotions finally reach boiling point she loses control and transforms into the “mad woman in the attic” so central to the novels Jane Eyre and, later, Wide Sargasso Sea. Furthermore, the way in which the novel spans the lives of a series of generations and explores the interlinked fates of successive generations could be seen as a parallel of Gabriel García Márquez’s Cien Años de Soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude) and maybe even Isabel Allende’s La Casa de los Espíritus (The House of the Spirits). However, Esquivel’s novel is much more optimistic – while the latter two novels end on an uncertain note that suggests that human beings are caught up in an endless cycle of suffering put into motion by the experience of their ancestors, the end of Como Agua Para Chocolate embraces modernity and outdated, oppressive traditions are taken with Rosaura to the grave. So, while Esquivel is conscious of the way which tradition shapes and cultivates identity, she is confident that humans can evolve beyond this, and beyond the suffering which plagued their ancestors. In a way, this is expressed through the literary references so present in this novel: Esquivel is at once respecting literary tradition and how it has influenced literature up to this point, and carving the way for new traditions in the future.

One thought on this article.