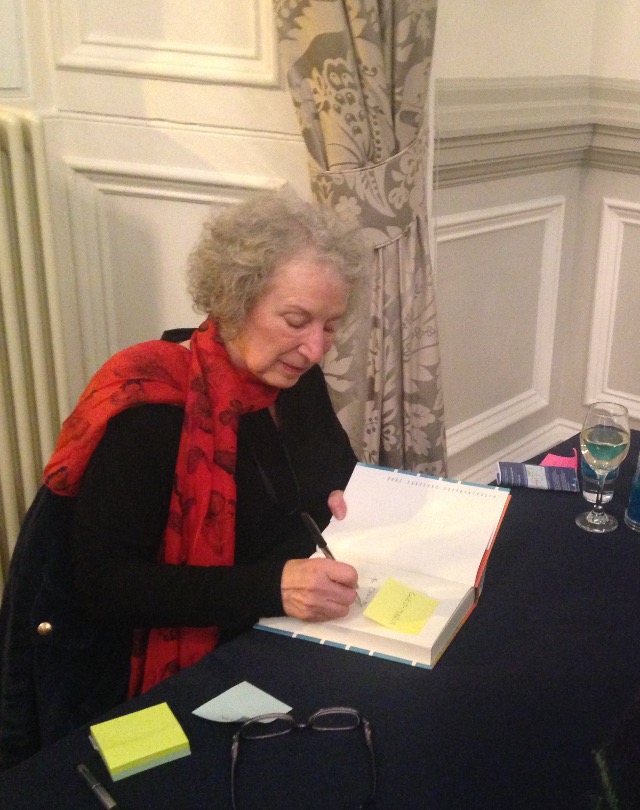

Margaret Atwood signing copies of The Heart Goes Last at a Blackwell’s Bookshop event, Edinburgh, 24th September 2015.

Margret Atwood released her latest dystopian novel on 24th September. It is called The Heart Goes Last and is her first novel in fifteen years. A fantastically dark, in-depth look at relationships, community, and society, with the unique addition of sex robots, Elvis-impersonators, and dominatrix-like sex slavery, it has inevitably received a controversial reception.

The Heart Goes Last differs in many ways from her best-loved works and, consequently, responses from fans and critics alike range from enthusiastic to scathingly disappointed. Sarah Lyall ends her The New York Times review by recommending that those considering this novel should instead “lie back and think of something else.” The reasons for such disappointment vary but can be summarised as follows: the tone throughout is random and inconsistent, there is a lack of in-depth analysis of the dystopian concept, and the dystopia is supposedly overcrowded with too many outlandish images and plot turns.

The scene is set in a future society which is facing the aftermath of a serious economic crash. Society has fallen apart in its poverty, patrolled by criminals and gangs. Innocent working people, like Charmaine and Stan, are turned onto the streets in bankruptcy. Living in their car off bar tips, Charmaine hears of a highly selective, secretive social experiment that allows for a seemingly ‘better’ existence – without hunger or violence – known as ‘Project Positron’. Despite warnings from Stan’s brother and Stan’s own misgivings, the couple sign up, signing away their independence in the process. The society they have signed themselves over to functions by a system of rotation. Each month, half the citizens are imprisoned, forced into grueling manual labour, while the other half lives in 1950’s style utopian comfort, with plentiful food and high quality accommodation, employed as prison guards or more rewarding roles supporting their community. They then switch existences with their ‘alternates’ for the following month, and so on. Charmaine and Stan both illegally develop obsessions for their alternates, Jocelyn and Phil, and their marriage in this utopian bubble soon disintegrates to mayhem.

The change in tone and ‘lumped together’ feel of the novel has been attributed to its initial internet serialization, and the effects of such a process are definitely evident within the text. Atwood’s writing has become slick, concise and distilled in its disturbing, potent imagery and plot twists. It engages the flitting and fleeting minds that browse today’s internet with its sensationalism, its dark comedy, and its view to thrill and entertain as well as to educate. The image of the male form mid-intercourse resembling a galvanized frog is a particular favourite of mine. Yet is this change in style necessarily a negative direction? Atwood has an established online presence and an active Twitter account. She bravely pushes and shapes her writing to fit the new parameters of culture and value that the internet has created in a way which perhaps less confident, less celebrated authors would never dare to do. In his The New York Times review, Mat Johnson celebrates the changeability and variety of Atwood’s tone, praising it for how it differs from his preconceived notions, creating something new, unexpected. He writes that he enjoys giving up his footing to Atwood since “one of her greatest gifts is unsettling the reader”. The internet provides Atwood a playground to push her writing to extremes of dark fantasy and, though the stylistic effects may not be traditional of the novel, they herald a new, evolving age of writing and thought, where fan-fiction and internet series may become the next W. H. Smith bestseller.

Many critics are also picking up on the weak economic and academic basis of Atwood’s dystopia. They complain that the restricted knowledge that she allows her protagonists, and by proxy readers, as to how and why Positron and Consillience function, is due to her own lack of understanding of what she describes, rendering her social critique weaker. I think Atwood has made a conscious choice to focus on the internal lives of these future citizens. Stephanie Merritt (The Guardian) argues that the world Atwood depicts is “all too horribly plausible.” Part of the reason Atwood is able to create this effect is because she focuses on human flaws and reactions. Her focus is not the politics or the economics of the future, though they play a significant role in the overall message. Her focus is her characters, the lens through which we see her dystopian world. The novel develops to be more than a mere apocalyptic solution to poverty and homelessness; it becomes a more complex exploration of sexual desire and human relations. She puts existing and universal flaws, weaknesses, and desires into extreme, dystopian settings so as to explore them in a new light. It leads to a consideration of whether society as we know it is a dictator of human action and mentality, or a reflection of our natural state. Atwood said in an interview about the dystopias she writes, “I think I’m just writing reality as it is unfolding.”

What makes The Heart Goes Last different from the dystopian formula of 1984, Fahrenheit 451, We, or Brave New Worlds is that Positron is originally a utopian solution to a dystopian problem that then decays (and becomes, once again, dystopian). The other titles I have cited follow a more traditional formula of an unimportant, obedient citizen realizing the degraded and false nature of his society and undergoing a transformation to rebel. Here, Consilience’s continuous degradation is central to the plot. This degradation, and the disintegration of the marriage of Charmaine and Stan in this utopia, highlights a message that is again slightly different from the traditional dystopia: that it is a human flaw rather than an extremist government or state (therefore a small elite of humanity) that is responsible for the dystopia. As Stacy May Fowles says of the struggling relationship of Charmaine and Stan, “picture-perfect boredom begets self-manufactured strife.” Where traditionally the dystopian protagonist seems to rage heroically against an alien and dehumanized government of oppression, Atwood focuses instead on a petty dysfunctional marriage in the heart of an increasingly ludicrous, petty, dysfunctional dystopia. She is exploring the base and imperfect human nature that has led her created world to its degraded state.

Yes, if you were expecting another The Handmaid’s Tale, you may be disappointed. But the concept of literary and stylistic progression, of originality, requires risk. It requires the ludicrous and the unconventional, the risky and the unsettling, the non-conforming and the nonsensical. Atwood has tried something new. Not only does her extraordinarily tech-savvy (given her ripe old age of seventy-five) means of online serialization demonstrate this, but also her deviance from the traditional characteristics and tick boxes of the dystopian genre (of which her famous works are held up as icons). How successful her attempt at change is is clearly debatable, and I have read many wonderfully argued reviews of this book, both bad and good, while researching this article. I myself have come to one simple conclusion: however different and strange and ludicrous, it is definitely worth a read.