Have you ever referred to something as ‘the Holy Grail?’ Something that you value highly, perhaps even something that changed your life? There is a whole wealth of history behind the object of this common saying, originating in Arthurian legend from the medieval period.

The earliest record of the Holy Grail can be traced back to the twelfth-century French poet Chrétien de Troyes. His unfinished poem, Perceval, or the Story of the Grail, refers to a ‘Grail’ that has other-worldly qualities including the ability to emit its own light. Chrétien describes how: ‘So great a brightness shone around, / And cast its light, the watchers found / The candlelight grow dim as, far / Off, dims the brightness of a star, / When the sun rises, or the moon.’ Chrétien sets apart the Grail from other precious objects, saying it was ‘Doubtless of much greater worth / Than all the other stones on earth.’ In addition to its beauty, Chrétien later reveals through Perceval’s hermit uncle that the Grail has sustained the wounded Fisher King for over twelve years: ‘A single host, assuredly, / That in the grail one brings to him, / Sustains and warms the life in him. / So holy a thing is the grail.’ This is the first time the Grail is referred to as ‘holy’ and is linked to Christianity. The ‘host’ taken by the Fisher King is the name of the bread consumed by Christians during the Eucharist, and is symbolic of Jesus’s body.

The links between the Holy Grail and Christianity are magnified by the thirteenth-century French poet Robert de Boron. He is the first to connect the Grail with Joseph of Arimathea, who the Bible says buried Jesus after his crucifixion. In his poem Joseph d’Arimathie, Robert says the cup used by Jesus in the Last Supper is the Grail. He intensifies the holiness of the Grail by describing how Joseph used it to catch the last of Jesus’s blood from his wounds after being crucified. After Jesus has been resurrected, he appears to Joseph and tells him to keep the Grail, saying it contains the power of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. He says that those in the presence of the Grail will feel profound spiritual joy and contentment. But like Chrétien, Robert shrouds the Grail in ambiguity, claiming Jesus told Joseph secrets about the mystery of the Grail that he could not dare reveal to the reader. In his subsequent poem Perceval, Robert retells Chrétien’s poem but aligns it with ideas from Joseph d’Arimathie. Here, Perceval is a descendent of Joseph and is revealed to be one of the three keepers of the Grail prophesised by Jesus. Like Joseph, Perceval is also told the secrets of the Grail, but they are not revealed to the reader.

The lore of the Grail is expanded upon further by the fifteenth-century English knight Sir Thomas Malory in his seminal collation of Arthurian works titled Le Morte d’Arthur. In this version, the Holy Grail comes into the presence of the entire Round Table:

Then there entered into the hall the Holy Grail covered with white samite, but there was none might see it, nor who bare it. And there was all the hall fulfilled with good odours, and every knight had such meats and drinks as he best loved in this world. […] then the holy vessel departed suddenly, that they wist not where it became.

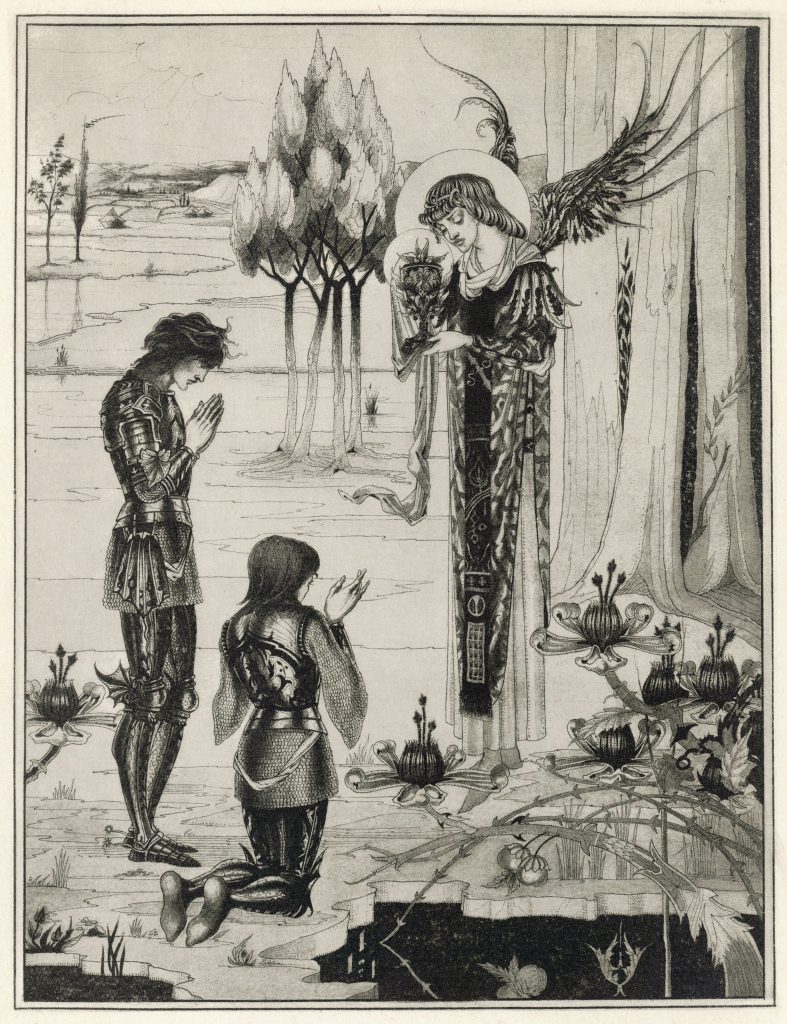

Although many knights including Perceval embark on a quest for the Holy Grail, only one, Sir Galahad, is successful. He sees ‘the Holy Vessel, and a man kneeling on his knees in likeness of a bishop, that had about him a great fellowship of angels, as it had been Jesu Christ himself.’ The ‘man’ actually turns out to be Joseph of Arimathea, who tells Galahad he is able to see the Grail because he has never sinned. Malory portrays the Grail as being the ultimate object of self-fulfilment; Galahad no longer desires to live in the world but instead asks God to take him up to heaven, saying, ‘for now I see that that hath been my desire many a day.’ Because the other knights of the Round Table have sinned at some point in their lives, the Grail is unavailable to them. Even Galahad’s own father Lancelot is barred from the Grail because of his infamous affair with King Arthur’s wife, Guinevere.

According to Malory, after Galahad saw the Holy Grail, a hand ‘came right to the Vessel, and took it […] and so bare it up to heaven.’ However, many people believe that the Holy Grail is still somewhere on this earth. According to BBC travel, the most likely location for the Holy Grail is the Valencia Cathedral in Spain, as there is a relic there which aligns with the description of it. Despite this, it cannot be proven, showing how the Holy Grail remains as mysterious today as in Chrétien de Troyes’s first portrayal of it.

Featured image: Jametlene Reskp via Unsplash