Everyone has that one book that inspired their love for reading. Those of us lucky enough to be studying English literature know something else: there is also a book that sparked a passion for reading and analysing. For me, that book was Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca; a book full of feminine energy, gothic elements and mystery. Whilst I’ve since expanded my reading repertoire, I always turn back to this text for comparison or as a point of contrast. This isn’t to say that I’m studying English because of one book; rather, this is the book that led to a whole host of texts that found themselves on my bookshelf.

‘This isn’t to say that I’m studying English because of one book; rather, this is the book that led to a whole host of texts that found themselves on my bookshelf.’ Image Source: Flickr

I think that literature has multiple layers of value. First and foremost, it provides an alternate universe in which we can lose ourselves. It is no wonder that children, and even adults, enjoy immersing themselves in the world of Harry Potter or The Hunger Games, and the same can be said for more canonical literature. Even seemingly realist texts that relate to everyday life have differences we can find interesting or unreal. For instance, Austen’s Pride and Prejudice shows young girls in the process of marriage which, in some 21st century readings, is far off, or not as prominent in our own lives. Books allow us to escape our own reality and see the world through someone else’s eyes.

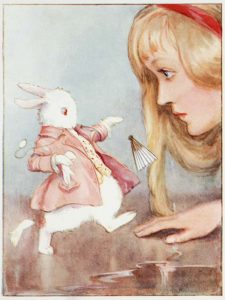

Aside from this, I study literature for its profound, deeper meanings. At school, we are taught to be critical when approaching texts, but tend to use basic critical frameworks. Albeit interesting, for me it is the combination of applying multiple, even contradicting, theories with my own opinion when reading that indicates its true value. Take the example of Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. If I read this in its context, it becomes an allegory for the tyrannical rule of Queen Victoria I, ergo literature becomes historical and informative. Yet there are so many other ways to read this ‘children’s’ story. Some have argued it represents the process of growing up, the absurd age hierarchy within families, female repression, female rebellion, or even the effects of drug use. Ultimately, I find that the use of one short text to reveal multiple truisms is what teaches us about the world, in ways we may not have even considered ourselves. Who would think to deconstruct language to the point where we tear apart seemingly ordinary words and begin to question the stability of language, as some critics do when studying Carroll’s novella?

This is the reason I am studying English at Durham this year. I want to learn more about different approaches we can take to literature and, by consequence, the world as a whole.