Taken by MarineDrive from: Wikipedia Commons

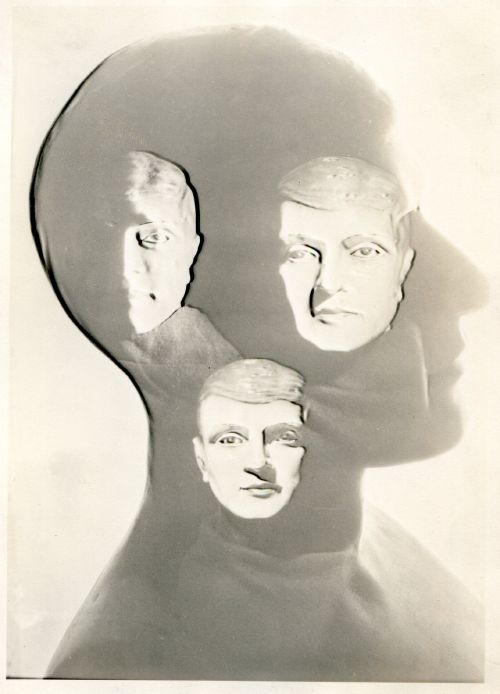

Introspection: ”Examination of and attention to your own ideas, thoughts, and feelings.” – Cambridge Learner’s Dictionary

Introspection is often neglected amidst the many overwhelming preoccupations that bombard us daily. Whether it be compulsive smartphone use or simply habitual conversation, the value of reflecting pensively about one’s own mind has nearly been lost. While deep philosophical thinking may not necessarily involve staring into a blank wall or gazing at the stars, devoting time to introspection shows us how little we actually know about ourselves.

Intuitively, we know that the human mind is a mystery; emotions being a property of such a mind further add to its complexity. On certain days we may feel sad for no identifiable reason. On other days we may be more irritable than usual or perhaps suddenly anxious with no particular cause. We may be detached but yearn for companionship or we may be shy in the workplace yet confident among peers. Such examples provoke us to think about the complexities of our individual mind in an effort to gain understanding. When we avoid introspection, we invite our emotions and cognitive idiosyncrasies to linger and slowly take over our lives. In turn, we develop alcoholism, nicotine addiction, insomnia, depression, rage, or impatience. The majority of such are simply symptoms of neglected thoughts and feelings.

As daunting and difficult as the practice of introspection may initially seem, solely relying on external (situational) factors to explain the way we are wired will inevitably end in dissatisfaction. For example, in explaining one’s anxiety, one should not only examine their workplace or financial status as potential sources, but perhaps a traumatic childhood event or one’s estranged relationship with their father. As a result, acknowledging these more nuanced factors will ideally lead to a more satisfying understanding of ourselves as characters.

Taken from: Bighappyfunhouse

When done habitually, one may see introspection as a form of philosophical meditation. Contrary to this, some may argue that introspection can psychologically affect us negatively rather than positively. In fact, renowned philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche supports this argument by stating that a complete understanding of human thought and reality would make existence unbearable (R. Lanier, 2017). However, it is important to note that the practice of introspection does not aim for complete and truthful understanding but rather probable understanding. Instead of discovering definitive truth we use conjectures and assumptions to explain oneself, hence the term ‘probable’. This does not diminish the value of introspection as such conjectures and assumptions are the closest truths one can fathom.

It is also important to note that introspection is not exclusively a mental practice. Contemporary philosopher Alain de Botton writes that introspection requires ‘’a time of day where nothing much will be expected of us’’, a time ‘’when we are free to devote ourselves to our deeper, more fragmented and mysterious selves’’ he continues. Since a complete outline of practical techniques would be longer than a standard article, one may learn more by reading de Botton’s guide here.

While it may seem difficult to think clearly about ourselves, introspection is nonetheless a necessary practice that preludes an enlightened life. When conducted habitually, one may find themselves more honest, forthright, and forgiving towards their character. As Greek philosopher Socrates famously stated: ‘’the unexamined life is not worth living’’.