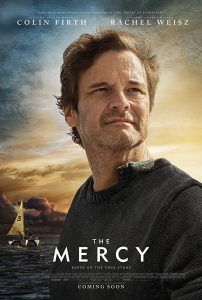

Poster of the the film ‘The Mercy’ (source: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3319730/mediaviewer/rm3108130816)

‘The Mercy’ is an unrelenting tale of pride, tragedy and what it takes to make history. “Men do not decide to become extraordinary,” remarks Edmund Hillary (the man who would later go on to climb Everest) at the film’s opening, “They decide to achieve extraordinary things.” These words, and no doubt the threat of financial ruin, are no doubt what drove Donald Crowhurst to attempt to circumnavigate the world and ultimately suffer the consequences of own his ambition. Once headline news, and now almost swallowed by history, Crowhurst’s fateful decision to enter the 1968 Golden Globe Race is one steeped in sadness; desperation and torn between continuing on with his journey to certain death or returning to humiliation and loss of his home (which he’d staked on the race), caused him to falsify his positions, all the while a media storm was being whipped up at home. Director James Marsh treats the subject matter with the sensibility it deserves whilst Colin Firth’s turn as the doomed sailor paints a painful picture about Crowhurst’s slow descent into madness and anguish.

For those unacquainted with the story, you could be forgiven for believing that this is a classic underdog tale; the film’s first act is filled with inspiratory nuggets such as “dreams are the seeds of action” and Firth is likeable, he’s someone that you want to succeed and root for. No doubt, this seemingly makes it all the more crushing when the carpet is pulled from beneath you, and the true tragedy of the tale is exposed. Knowing the true story from the get-go lends itself to the perception of hindsight; as Crowhurst’s date for departing for the race draws inevitably closer –with his trimaran, the Teignmouth Electron, far from completion and riddled with mechanical flaws– an unmistakable sense of dread arises. Firth plays to his strengths in these moments; his fear is understated but present, the signs of a man wishing to be strong, but finally realising the gravity of his decisions. It’s subtle, poignant acting made all the more harrowing as the film nears its end.

Scene from the film ‘The Mercy’ (source: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3319730/mediaviewer/rm774199552)

Crowhurst’s passing is mostly shrouded in mystery; unknown whether he was thrown overboard, or chose to take his own life, and the film remains mostly ambiguous on the point. Enough inferences are there for the audience to decide what they believed truly happened to the ordinary man in search of extraordinary. Firth’s final scene is emotionally draining. His calibre has an actor has been solidified in recent years with roles in the BAFTA winning ‘A Single Man’ and his Oscar triumph in ‘The King’s Speech’ and it is true that his tasteful interpretation of Donald Crowhurst’s story should join the roster amongst some of his most highly regarded roles. Of particular note is the actor’s adept ability to reflect Crowhurst’s descent into mental instability; from the moment he sets sail, it is possible to chart each emotion the man is feeling. The crushing isolation and suffocating loneliness is made all the more poignant by phone calls home to his wife Clare (Rachel Weisz) and children. It is a truly disturbing sight to behold as Donald loses his grip on sanity and starts to bear the brunt of the world on his shoulders, just as Firth carries the weight of the film on his.

Scene from the film ‘The Mercy’ (source: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3319730/mediaviewer/rm521147904)

With a story focused centrally about a man on a boat, creating an atmosphere and tension would have been a paramount consideration of the creative team. Most of this is generated incredibly successfully, and albeit subtly, through the late Jóhann Jóhannsson’s score. During the scenes pre-dating the voyage, the score is akin to that of a light-hearted film producing the impression of familial bliss and happiness. By contrast, when Crowhurst is out alone on the vast, bleak ocean, the score is subdued and makes way for particular emphasis on the rattling of the rig, the wailing of the wind and the waves of the ocean; it is consuming, isolating and deeply unsettling.

However, music can only tell so much of a story and the constraints of history and accuracy limit just how engaging a biopic so isolating can be. For this, there are moments when the film can feel flat. Seemingly, ‘The Mercy’ somehow lacks the spark of Marsh’s outing ‘The Theory of Everything’, which was met with widespread critical acclaim, and is instead more of a documentary than an exploration of Donald Crowhurst’s mentality. Marsh paints the man as a tragic hero, whereas a more suitable presentation may have been that of the anti-hero; someone whose intentions are noble, but whose actions stray into the grey area between the good and the bad. In Crowhurst’s own words, he commits the ‘sin of concealment’ wandering from the road paved with good intentions. The film is quick to point the finger of blame at the press and namely at David Thewlis’ reporter-turned-publicist but, no doubt, in reality it is not quite so easy as to pin the responsibility on one single party.

The film draws near its close with contrasts between Crowhurst’s loneliness and his wife Clare who has become embroiled and surrounded by media interest. These closing scenes give Weisz something to do, she is otherwise drastically under-utilised for the majority of the film’s duration, but she is given one of the more resonant and memorable lines; “Last week you were selling hope,” she rallies defiantly at a sea of reporters, “Now you are selling blame.” No doubt, this line encapsulates the emotions felt by the wife and children left behind in the wake of tragedy. These final moments are designed for emotional impact and they land effectively producing some particularly poignant and thought-provoking moments.

Scene from the film ‘The Mercy’ (source: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3319730/mediaviewer/rm539318528)

All in all, ‘The Mercy’ is a raw and brutal retelling of a real-life tragedy. It battles with the concepts of ambition, greatness and the heavy cost sometimes incurred when attempting to achieve both. Although a little rocky in places, the biopic, overall, depicts a story worthy of being told and treats Crowhurst’s tragedy with grace.