The Queen’s Gambit is one of the very best Netflix shows to date.

The headline premise, however, does it no justice at all. Whilst I am sure that there are many who would be interested in the rags-to-riches story of a chess prodigy, it would be criminal for many more to overlook this drama because of a description which barely scratches its surface. You need never have so much as glanced at a chessboard in your life to be able to appreciate The Queen’s Gambit for being the thrilling, raw, and charismatic sensation that it is.

This seven-episode limited series, based on the 1983 bildungsroman novel by Walter Tevis (author of bestsellers such as The Man Who Fell to Earth and The Hustler), follows the life of young Beth Harmon and her rise through the chess player ranks whilst battling addiction, the infuriating expectations of others, and her own tragic past. We first encounter the sullen nine-year-old Beth as she begins to secretly learn chess from the janitor at her orphanage. A place where handing out ‘vitamin’ tranquiliser pills to keep the girls in check is the norm. The discovery of her genius talent for the game ignites a spark which continues to flicker and burn at the heart of the series, taking her all over the world and into the acquaintance of a kaleidoscope of characters. The plot spans from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s, with brilliant costumes, makeup, and music to match.

Beth undeniably adds rock-and-roll style to a game so often associated with the quiet, geeky kids hiding away in the library (I should know). Her flaming-red bob is hard to forget.

What is perhaps most striking of all is the way that Beth is both the protagonist and antagonist of her own narrative. She has passion raging through her being. An ever-burgeoning sense of pride and anger then, coupled with her frightening dependence on tranquiliser drugs and any alcohol in sight, constantly threatens her downfall. Confidence wavers and rationality is her fickle friend. She is a character – so meticulously and artfully played by Anya Taylor-Joy – whom we wish simultaneously to love and to scream at.

Anya Taylor-Joy at the 2018 San Diego Comic Con. Image by Gage Skidmore available on flickr.

Early on in Beth’s story, we hear ‘Girls do not play chess’. Watching her inhabit this male-dominated field, the audience can do nothing more than applaud her depiction as a calculating and lethal player – one who rarely breaks into a smile and expertly pierces the grand-masters with her penetrating eyes. She truly does beat them at their own game. Though depictions of sexism are perhaps unrealistically underplayed, any other female players are always conspicuous by their absence. We must remember that this is still the case today and that no woman has yet won the World Chess Championships.

In fact, for the most part, the men are incredibly decent. This is rare. So often in dramas, the female-identifying protagonist is subjected to all manner of suffering at the hands of frankly psychopathic male figures. As though this is a necessary step in every woman’s life in order for her to reach self-fulfillment by the end of her narrative. We know it is an undeniably terrible and regular reality for women all over the world. I cannot, therefore, begrudge the existence of these honourable and amenable men who Beth defeats and befriends, because it is a refreshing change to watch.

The series owes its cinematic visuals and affecting dialogue to writer and director Scott Frank, who masterfully unfolds the plot with careful attention to pace and the passage of time. Beth’s journey into maturity is handled seamlessly. The genius scenes where she visualises her chessboard on the ceiling offers us the privilege of delving so deep into Beth’s psyche that it is hard to surface for air when we press pause.

Also, feel free to play spot the actor while you are watching. There are some truly phenomenal performances to enjoy. The eternally youthful Thomas Brodie-Sangster (I refuse to believe that he is thirty-years-old) of Love Actually fame, plays the enigmatic Benny Watts, a cynical chess champion whom Beth must defeat and surpass. Harry Melling, known to most as Dudley Dursley from the Harry Potter franchise, may be unrecognisable to you as Harry Beltik, Beth’s first major opponent. And whilst the maternal figure of Alma Wheatley may not be recognisable, you may well know Marielle Heller for directing credits on The Diary of a Teenage Girl and Can You Ever Forgive Me?. Heller manages a nuanced and tactile performance which leaves the audience on constant tenterhooks.

Thomas Brodie-Sangster at the 2015 San Diego Comic Con. Image by Gage Skidmore available on flickr.

Some scenes possibly lack the catharsis which has the potential to occur. Sometimes I feel that Beth ought to say more in her defense, or that characters do not always get their just desserts, or that proper goodbyes are not permitted. This can, at times, be truly infuriating. Perhaps that is the point. A part of the show’s magnetic and addictive quality – to keep us teetering on the edge of complete satisfaction. Furthermore, whether a person could truly function at as high a level as Beth accomplishes, when their body is so engulfed by the effects of substance abuse, rather defies the artistic license we permit these dramas to have. Indeed, what makes this all so incredible is that it is not based on a true story. It may seem counterintuitive to say so. However, the point is that I finished episode seven thinking ‘wow, what a story and what a life to have lived’, because it seemed beyond belief that this could happen, whilst simultaneously having enthralled me into believing every single scene.

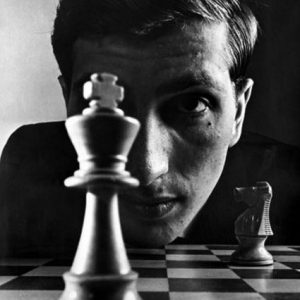

Bobby Fischer. Image by PhillipRother available on flickr.

There are certainly real life chess grand-masters who Tevis must have drawn upon, such as the American Bobby Fischer, who’s match against Russian grand-master Boris Spassky in 1972 was deemed to be a major event of the Cold War. But the powerhouse Beth Harmon is indeed fictitious, and fantastic in her own right.

All in all, maybe it is something of a tragedy that this is a limited series and will not be getting a follow up. If you spend time with these characters and these complex games, both of chess and of emotion, I am in no doubt that you will come to love it as much as I have. Then, you may also agree with me that it needs no follow up. It is a self-contained world: beautifully crafted in much the same way as Beth describes the chessboard. ‘Chess isn’t always competitive. Chess can also be beautiful. It was the board I noticed first. It’s an entire world of just 64 squares. I feel safe in it. I can control it. I can dominate it. And it’s predictable, so if I get hurt, I only have myself to blame.’

Feature image by Evonne available on flickr.