Can any degree of violence be considered ‘justified’ in the media?

Man, there’s a lot of violence out there. Stupendous, stupefying, insane amounts of violence. Only earlier today, I rose above the carnage of the French Revolution by dispensing with petty political differences and instead murdering everyone who happened to be holding a sword in Paris. Then, I saw two Mongol warlords whale on each other with massive weapons until one of them just straight up cut the other’s head off. That’s a lot of death to stomach before lunch.

Of course, I’m talking about Assassin’s Creed Unity and the Netflix series Marco Polo respectively, but it’s the debut game from Destructive Creations that has made me pause to even consider the brutal level of carnage they contain. The game, Hatred, hasn’t even been released yet, but a teaser trailer was enough for it to make an impact. The boiled down stereotype of a columbine-style, death-metal nutjob tells us that he hates everything so much that he’s going to go on a rampage in the requisite throat cancer growl of a voice. Then, he steps outside his dingy home and a mash-up of gameplay footage follows where the player takes the character on his rampage, slaughtering everyone he comes across.

It’s genuinely disturbing stuff. The short trailer is enough to make most people deeply uncomfortable. Unsurprisingly, it has generated plenty of controversy, exacerbated by the game being listed on Steam’s Greenlight service, then kicked off after a few hours, then being re-listed on it in the next day. However, the core debate around Hatred is fascinating because it forces us to ask the question, aren’t we doing the same thing in other games anyway? Is the idea of it uncomfortable just because it strips away the justifications other games provide for player-driven genocide?

The argument presumes that Hatred is portraying the real sentiment under violence in all games, but I’m not convinced it isn’t providing its own context and justification. Sure, games like the Assassin’s Creed series give us the justification of being the hero, but I’ve never felt this is containing my real fantasy of unleashing limitless rage through endless slaughter. It also doesn’t help that the developers behind it try to dress it up as a heroic cry against political correctness in weird, broken English on their website. Hatred isn’t exposing the foundation of other games, it’s providing a different fantasy of its own.

One of the main problems with violence in games is that you pretty much have to put a lot of combat in to fill them up with gameplay. Even The Last of Us, a complex, beautiful game, includes 250 human kills on a regular play-through. True, the game is far from celebrating this violence and it would take another column to scratch the surface of how the game is exploring it, but that’s still an awful lot of murder.

Another popular argument is that killing innocents is an option in other games rather than the objective as in Hatred. This especially appeals to me. Even for a game designed to be played long after the story is over like Diablo III, I struggle to keep an interest when any narrative reason is gone. I’ve never even gone on a rampage in GTA V.

But, still, even the option existing is a bit fucked up. Let alone the assumption that all those soldiers just trying to keep the peace in Assassin’s Creed deserve to be murder fodder. It’s hard even to point to Hatred as an extreme outlier. The most disgusting development of the news story was when some called for DLC (downloadable content) to put real-life targets of Gamergate in the game for virtual slaughter. Horrific, yes, but I exploded what was clearly supposed to be Mark Zuckerberg’s face in GTA V and didn’t have a problem.

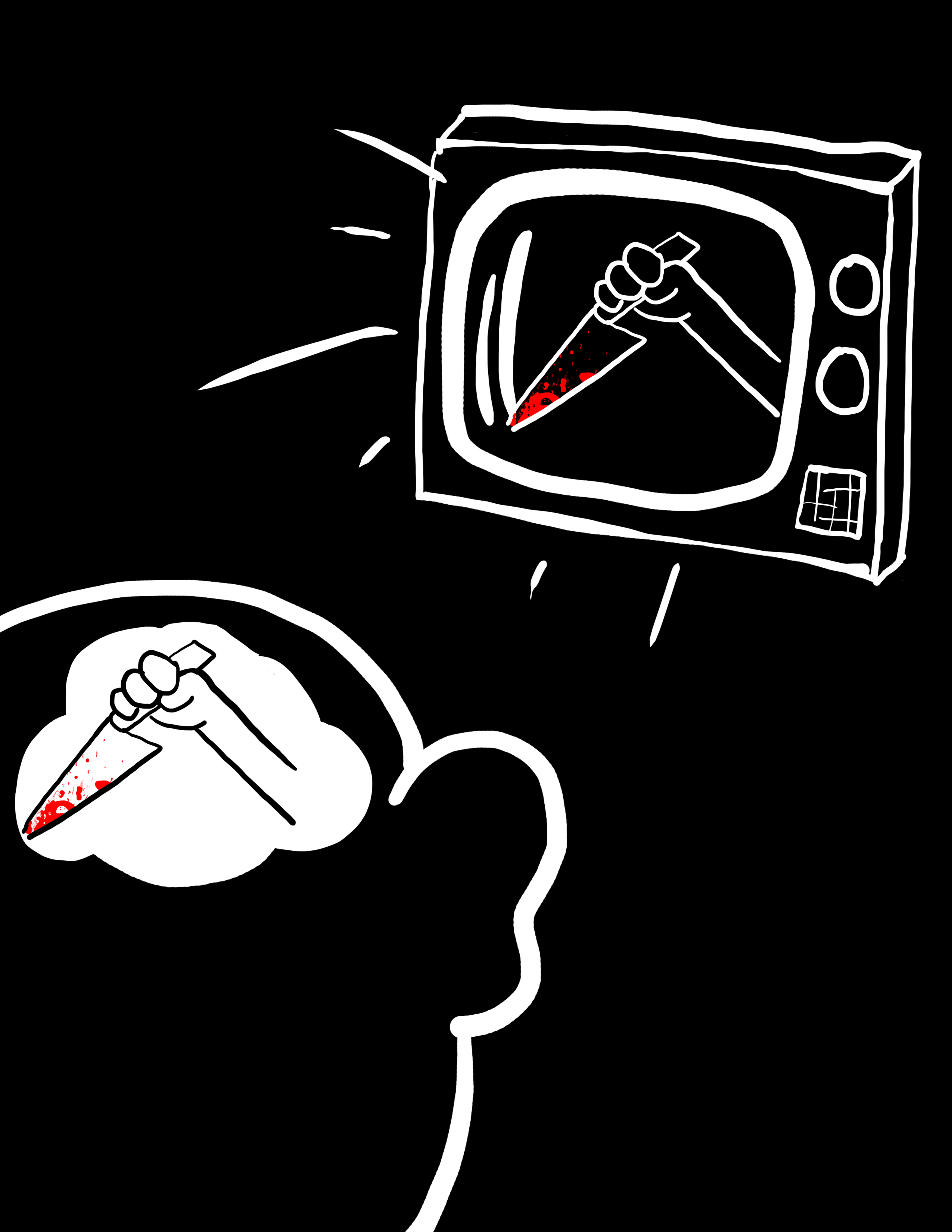

This is perhaps the most disturbing revelation, that some instances of violence in media disgust us and are condemned while others just aren’t. We can examine the context and find adequate reasons, but the whole process is thinking backwards. The reasons we come up with may fit, but at the time it was as simple as the fact that we were just OK with it.

Still, before asking the question of why we excuse or condemn different depictions of violence, it’s worth asking why we need to excuse or condemn it in the first place. The Raid 2 is an action movie, but it would be more accurate to call it a ballet of violence with its masterful choreography. Its story is by no means bad, but clearly exists to provide a frame for the heart-stopping fight scenes. Does this make it the same as Hatred? Again, I’d argue that rather than revealing what’s at the heart of other violent media, Hatred is very much providing its own context and fantasy for its violence. Its choice of serial killer fantasy is what makes it disturbing, more than the violence it contains, and the amazing physical capability and skill of the actors of The Raid 2 make for a much more comfortable artistic goal. If we can make this differentiation, can’t we just stop worrying about violence in media?

Nonetheless, it’s worth investigating the uncomfortable link between Hatred and other games and movies and all kinds of other formats. The argument of claiming violent art produces violent people should have long been put to bed by now, but it is just as extreme to claim that media and pop culture do not influence us at all. Just look at the movie Sideways, where a single scene featuring a wine snob praising Pinot Noir over Merlot boosted sales of the former and reduced those of the latter.

With many voices on the internet itching to find an extreme so they can pick a fight, admitting this can sound like the beginnings of a conspiracy to sanitise all forms of art into offence-free grey sludge. On the contrary, nothing about the Hatred debate has made me change or restrict any of the media I consume, but it’s important that it’s thought and talked about. The result may be an impasse, I’m still uncomfortable with the link between Hatred and the music, TV shows, films and games that I consume, but at least we’ve got our eyes open.