The Qur’an

In the wake of the recent death of King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, King of Saudi Arabia, much attention and criticism has been drawn to Saudi Arabia’s Islamic regime. Saudi Arabia conforms to the Wahhabi tradition of Islam, which, due to its fundamentalist and literalist nature, has been held as responsible for much of the rise of violent political Islam in the 20th century, which is so prevalent today. But does Wahhabism deserve this reputation, or has its meaning been twisted by modern radicals to justify their hateful ideology?

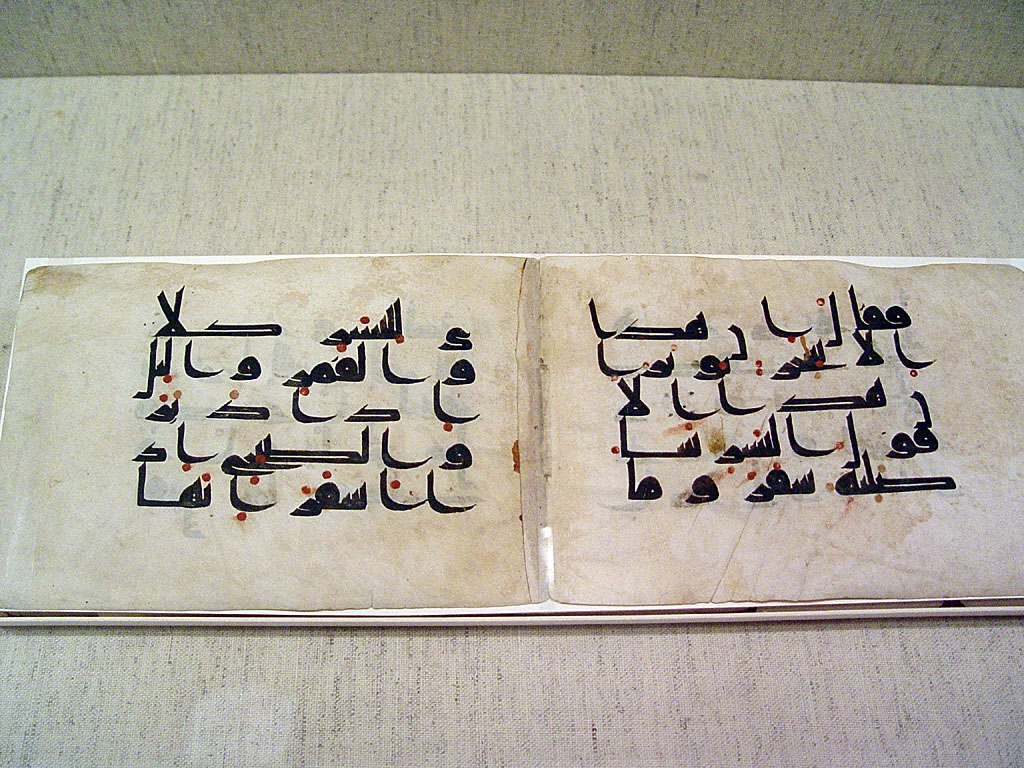

Firstly we must consider what Wahhabism is and what it preaches. Its founder was Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab, born in 1703, twelve centuries after the Prophet. A radical, al-Wahhab challenged the established religious traditions, including standard interpretations of hadiths (what the Prophet is recorded to have said and did in his lifetime). This idea was controversial because it meant questioning the ingrained idea that religious truth is passed down from one generation to the next, unaltered. al-Wahhab argued that the Qur’an has absolute authority over hadiths that have been interpreted by the ulama (religious scholars). Ibn Abd al-Wahhab’s aim was to purify Islam, protecting it against idolatry, against Jewish, Muslim and Indian schools of thought which had seeped into Islamic practice, and against polytheism, idolatry, rituals, and custom. al-Wahhab wanted to reduce Islam back to its core truth: tawhid (Islamic monotheism).

Ibn Abd al-Wahhab was concerned with corruption and believed everyone (including women) should be able read the Qur’an and interpret it themselves. He stressed the need for constant reinterpretation of tradition within Islam because contexts always change. Yet here lies the central tension within Wahhabism: it stresses the need to go back to focus on the original text (which suggests a strict literal orthodoxy), yet also emphasises the reinterpretation of meanings to fit with the time and context (suggesting that Wahhabism could be liberal and flexible). Perhaps the overemphasis on the former teaching explains why Saudi Arabia is such an ultra-conservative and strict Islamic country, especially for women.

So how can Wahhabism be linked to Islamic extremism? Well, this is mainly due to the alliance between Ibn Abd al-Wahhab and the House of Saud (the rulers of what is now Saudi Arabia) in 1744. Ibn Saud would protect and propagate the doctrines of Wahhabism, while Ibn Abd al-Wahhab would support the ruler of Saudi Arabia, supplying him with glory and power. Two generations after al-Wahhab’s death, the Wahhabis became more and more violent, focusing on state expansion and the accumulation of wealth. This was demonstrated most when the Wahhabis destroyed Shi’ite religious shrines in Karbala (Iraq) in 1802, wrecking the relationship between Wahhabis and Shi’ites, which has never recovered. This also started the prevalent narrative that Wahhabis are violent sectarians.

In the 20th century, political Islam began to take shape in Egypt. Many Egyptian Islamists fled to Saudi Arabia, where they were given sanctuary, and soon infiltrated into the political class. This was worsened by Britain’s support for House of Saud’s right to establish the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia post-WWI. Saudi Arabia’s consequent oil boom not only enabled the Wahhabi majority to further promote their religion (with its extremist undertones) in Saudi Arabia, but around the world. The West, needing oil and a strong regional ally, ignored this uncomfortable fact.

But is this Wahhabism’s fault or the fault of extremists with a chip on their shoulder? Ibn Abd al-Wahhab even wrote about imposing limitations on fighting, arguing that it should be in self-defence and that no civilians should be killed, nor men of religion (including rabbis and priests). al-Wahhab also did not condone waging jihad to convert the masses – he only wished to invite people to be educated in Islam and Wahhabism. Arguably one of Wahhabism’s key teachings, that everyone should study the religious texts and evaluate them for themselves, has made it vulnerable to extremist and violent interpretations of the Qur’an and the hadith. Modern Wahhabism has possibly lost its spirit of reform and has not been evolving with the times as Ibn Abd al-Wahhab would have liked.

Wahhabism is a complex school of thought which seems to contradict itself: on the one hand, Ibn Abd al-Wahhab thought women should read the Qur’an as well as men and should have the same rights to education, yet on the other, he approved the stoning to death of an adulterous woman during his lifetime. In the same way, although Wahhabism has undoubtedly produced its fair share of Islamic extremists (Osama bin Laden in particular), it would be too simplistic to lay the blame solely on Wahhabism – the aggressive and hateful individuals who advocate violent jihad are responsible too.